© GalaxEye Space

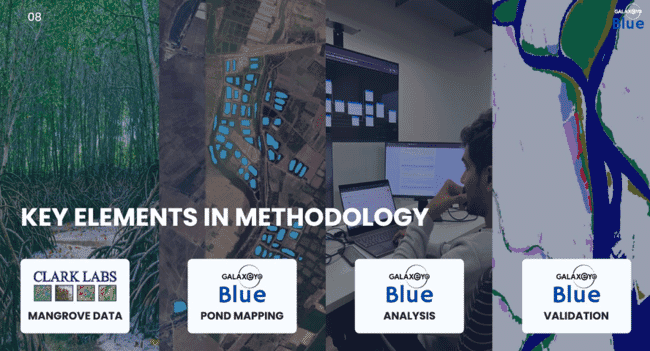

The analysis uses GalaxEye’s own aquaculture pond database and Clark Labs’ mangrove database (see image above). It shows that, from 1999 to 2022, only 0.3 percent of the area’s mangroves were converted into fish and shrimp ponds, while the total area covered by mangroves actually increased by 8 percent, debunking the myth that the recent expansion of shrimp farming operations has led to widespread mangrove destruction.

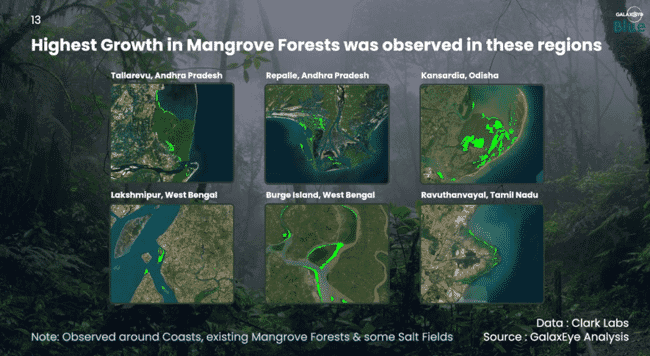

The majority of India’s shrimp farms are concentrated on the east coast, especially in Andhra Pradesh, but also in West Bengal, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu. This coast’s primary mangrove forests include the Sundarbans (West Bengal), the Bhitarkanika Mangroves (Odisha), the Godavari-Krishna Mangroves (Andhra Pradesh), and the Pichavaram Mangroves (Tamil Nadu).

It’s true to say that India’s east coast shrimp farms and mangroves compete for scarce land and data on mangroves from Clark Labs and analysis using GalaxEye Space’s database show that between 1999 and 2022, the land covered by fish and shrimp ponds expanded by 87 percent, while the total area covered by mangroves increased by 8 percent (see image below). In 2022, around 385,000 ha on the east coast was covered by fish and shrimp ponds, and around 260,000 ha was covered by mangroves.

© GalaxEye Space

Political support for mangroves

Amidst strong conservation and afforestation efforts, by both the Indian government and the private sector, as well as natural expansion of mangrove forests, the total area of land covered by mangroves increased by 20,000 ha between 1999 and 2022. However, while the total area under mangroves increased, around 8,800 ha of mangroves were lost, because of factors such as climate change, tropical storms, industry expansion, and agriculture. Over the same period, mangrove conversion to fish or shrimp ponds was limited to an area of 750 ha. To put this in perspective, this figure represents just 0.3 percent of the total land covered by mangroves and only 0.2 percent of the total fish and shrimp pond area. Placing these figures in context makes claims against India’s shrimp industry not only unfair and misrepresentative, but also unfounded.

A closer look at two of the states where mangroves and shrimp farming exist side-by-side: Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal. Andhra Pradesh is home to some major rivers: the Godavari, the Krishna, the Pennar, and the Vamsadhara. The majority of the region’s mangrove forests can be found in the estuaries of these rivers, but they also occur in smaller patches along the coastline. Despite the rapid expansion of the shrimp industry, and around 450 ha of mangroves being converted to fish and shrimp ponds, the area covered by mangroves in Andhra Pradesh grew from 32,047 ha in 1999 to 42,493 ha in 2022, an increase of 33 percent. This increase is a strong confirmation of conservation and aggressive afforestation efforts of India’s federal and state authorities.

Extensive shrimp farming has occurred there since the 1980s, but the mangroves have been protected from any encroachments from the industry since 1999

The majority of India’s mangroves are located in West Bengal, which is home to around 192,665 ha of mangroves, including a portion of one of the most famous and largest mangrove forests in the world: the Sundarbans.

Traditional shrimp farms have been active since the 1980s around the Sundarbans. These are large, multi-hectare ponds where farmers grow shrimp in low densities. The Sundarbans are now well preserved, and no significant destruction of mangroves due to shrimp farming expansion has occurred between 1999 and 2022.

This is slightly different in other coastal districts in West Bengal, where more intensive shrimp farming has expanded recently, and, despite local regulations, some mangrove conversion has occurred. The total land covered by mangroves in West Bengal slightly increased from 189,555 ha to 192,665 ha. This, again, illustrates the success of India’s mangrove conservation and afforestation efforts.

Why focus on the last 25 years?

You might ask why, I’ve chosen to focus on the period after 1999. Indeed, mangrove deforestation also occurred before 1999. But the COP 7 Conference in May 1999 was a key moment in the conservation of mangrove forests: many governments made firm commitments to mangrove conservation when the Ramsar Convention was approved. In the period before 1999, there was little consensus about protecting mangroves. Mangrove conservation wasn’t high on governments’ agendas, and mangrove conversion into uses including aquaculture was a more widespread practice.

Organisations like the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) also recognise 1999 as a benchmark moment in wetland conservation and ASC's standard prohibits the clearing of mangrove forests for the purpose of building shrimp farms. The standard also states that farms that were built before 1999 on land that was previously covered by mangroves, must rehabilitate 50 percent of the area cleared for the farm.

ASC also recognises that farms might have changed ownership multiple times in the last 25 year period, making it challenging to hold particular companies to account for previous deforestation. I, too, support this logic and therefore exclude the period before 1999 from the scope of this analysis. What’s more, I feel that looking back further does not feel particularly useful or relevant when we are talking about the accusations that are circulating today of “continuous” and “widespread” mangrove deforestation.

My personal view is that, when it comes to who is being accused, we should take the historical context into consideration, especially when making serious claims against particular players—in other words, it’s hard to hold the industry’s current leadership to account for practices that occurred such a long time ago, when the industry was still in its relevant infancy. These constitute practices that today’s leadership couldn’t influence or control, and that have since become highly regulated.

While the shrimp industry is vital for India because of its economic significance and the number of jobs it creates, mangroves are essential for coastal protection, biodiversity, and carbon sinking. It’s in the interest of the industry and the wider Indian society that the shrimp industry and the country’s mangrove habitats not only coexist but also flourish. If we take a moment to consider the market challenges the Indian industry faces in the wake of these claims, committing itself to supporting increased mangrove conservation and afforestation projects could significantly enhance its market image and consumer perception. According to Indian legislation, companies must spend 3 percent of their net profits on corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities; mangrove conservation projects would be a good place to start for some of the country’s shrimp exporters in light of this situation.

While some deforestation has indeed happened over the past 25 years, contrary to common belief the numbers show that the scale of conversion does not justify the accusations being put on the Indian shrimp industry: as proved in this analysis, the industry’s impact has actually been quite limited.

In my view, these claims are, therefore, unfounded, unfair and unjust. Even more, while the shrimp industry expanded rapidly during this period, the land covered by mangroves increased significantly. It’s essential to spread this message within the industry, to retailers, and to consumers worldwide: accusations like this don’t only damage the Indian shrimp industry but the global shrimp industry more broadly.