Photo: Fisheries Research Service

Almost immediately after the virus was reported in the Shetlands, fish from infected farms were removed and inspectors were making their way around the 42 fish farming sites within the newly established Control and Surveillance Zones. The efficiency of the reaction belies the severity of the problem, and may come to save this industry from the graver impacts that have come to dominate salmon fisheries elsewhere in the world.

It will take approximately six weeks to culture the samples and establish definitively the presence of the virus, but the first indications of the results should be known much sooner. The Scottish Industry has also initiated an investigation into the source of the outbreak, saying it will be "the subject of a scientific study to determine the source of this new infection, the distribution of the disease in the environment and the risk of further spread."

There has to date been one previous outbreak of ISA in Scotland, which occurred over the years 1998-99. According to figures from the Fisheries Research Service (FRS), the estimated cost to the industry was in the region of £30 million. In this initial incident prompt action succeeded in eradicating the disease, but other countries have been less fortunate.

Since it was first detected back in Norway in 1980's, ISA has posed a number of resilient problems for salmon farmers. To this day, it still hampers the Norwegian industry.

In the same year that Scotland managed to eradicate ISA for the first time, the average annual cost of the epidemic in Norway was US$11 million, while in Canada the virus was estimated to cost an average of US$14 million per year. The Faroe Islands paid the price of their entire industry when the virus hit in 2000, while the Chilean industry currently toils from a particularly severe series of ongoing outbreaks.

Chilean salmon exports are currently one of the country's most dynamic businesses, boasting over 800 salmon farms, with an annual turnover of more than US$2 billion. However, since the 2007 more than 100 Chilean fish farms have been affected. According to reports, approximately two per cent of farmed Chilean salmon die as a direct result of the virus.

The industry has since deteriorated drastically and consumer confidence is falling. SalmonChile reported that production could drop by as much as 20 per cent in 2009 – possibly to as low as 275,000 tonnes (13/10/08), a far cry from its heights in 2007 - when it was estimated to have produced just shy of 400,000 tonnes of salmon and reported export earnings of US$2.247 billion. As a result of large-scale unemployment and governmental failures unionists have been protesting on the streets Puerto Montt. Chile

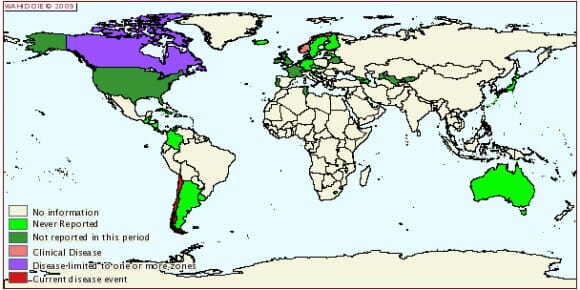

The Chilean salmon industry portrays the depth of this problem and there appears to be no solution in sight. Far from coming under control the virus continuously alludes preventative measures, passing through the safety net of the most stringent control measures in the world. According to figures from the World Animal Health Information Database, over the course of 2008 the ISA virus claimed an outbreak in Canada, 20 outbreaks in Chile and 14 outbreaks across Norway. Now, with the inclusion of Scotland, all the big salmon farming countries have recently suffered.

Disease Distribution Over the Last 6 Months

Image: World Animal Health Information Database

Image: World Animal Health Information DatabaseThe One that Got Away

Based on biochemical, physical, chemical, and structural characterization, ISA virus is very similar to members of the "flu" family, says the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Although there are no human food safety concerns, the mortality rates of salmon infected are highly variable, ranging from two to 50 per cent over one production cycle, but potentially affecting an entire farm in a matter of months.

Signs of infection in salmon include: lethargy; loss of appetite; gasping at water surface; pale gills; dark liver; accumulation of fluid in the body cavity; hemorrhage in internal organs and high of levels of mortality, but the global impact of the virus shows not only how devastating it can be, but also how difficult the problem can be to eradicate once it has firmly set in.

The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) says that vaccination against ISA was carried out in North America over five years, but the available vaccines did not offer complete protection. Similarly, the use of antibiotics is another ineffective solution and is one of many other factors that could lead the industry into deeper, longer lasting troubles.

There is evidence that poor sanitation, unnatural growth conditions, and environmental pollution are at the root of this problem. ISA is thought to affect fish in stressful conditions in highly increased rates. It has also been suggested that over crowded pens placed in close contact with one another are adding to the weight of this problem, whilst making it easier for the virus to harbour in large numbers and pass from one farm to the next.

The most effective way to combat the disease may well be with natural ecologically sound measures, quick response to outbreaks, removal of fish from site, sound disposal, clean farming conditions and well managed operations, but the cost to create these conditions will arguably be high and restructuring well rooted industries will not be easy to manage.

Whether the cost of implementing such procedures balance out in comparison with the current price of salmon on the market is yet to be realised.

Fishing for the Source of the Problem

Despite of previous investigations it has been difficult to pinpoint the exact factors pertaining to these outbreaks and even to source where the virus originated.

* "The subject of a scientific study to determine the source of this new infection, the distribution of the disease in the environment and the risk" |

|

Quote from the Scottish government.

|

According to the FRS of the Scottish Government, the ISA virus is spread through water. Once infection is established in a farm, other farms in the area are at risk. The risk of transmission is associated with infected biological materials such as animal wastes or discharges from normal culture operations and "untreated blood released into the sea", but there has also been evidence of "vertical transmission" via eggs or milt, says the FRS. It has also come to light that "other species of fish may be carriers" also. However, although other fish can harbour the disease, it only really affects the salmon industry.

The FRS say that the extensive testing of wild fish at the time of the outbreak in 1998/99 did find some evidence evidence of ISA virus in salmonid species, but prevalence of infection was low and there was "no evidence that this caused disease and no observations of clinical signs". There is no evidence from Norway, where ISA has been present since 1984, that ISA causes disease or harmful effects in wild Atlantic salmon at all.

According to a Geologic Survey conducted by the National Fish Health Research Laboratory, sea lice may play an important role as vectors that can enhance contagion during epidemics and evidence has pointed to certain species of fish and shellfish that can either accumulate the pathogen or transmit the disease. This research indicates that wild fish may become carriers and serve as potential reservoirs of infection

while the first Scotland outbreak proved inconclusive, it raised many questions about how ISA managed to penetrate the industry. Consequently it led to many perceived solutions that have since been implemented. The Scottish government says that importation of live salmonids is normally prohibited except from areas of equivalent health status and imports of live fish into Scotland have not been allowed from Norway, Chile or Canada as no salmon populations there satisfy the fish health requirements for import into the UK. Yet, with this second bout of infection, new questions are bound to be raised.

One report to come from the Fisheries Research Services Marine Laboratory in Aberdeen identified the critical role that the long-distance transport of pathogens plays in the emergence of novel diseases. Shipping is a major contributor to such transport, and the role of ships in spreading disease has been recognized for centuries.

"We present evidence of invasive spread of infectious salmon anemia in the salmon farms of Scotland and demonstrate a link between vessel visits and farm contamination", claimed the report..

Whatever the outcome, the source of these outbreaks must be traced and understood if the industry is ever to close it and secure their operations from this disease. Perhaps only then will the long apprehensive wait of salmon farmers in the Shetlands and the world-over ever come to an end.

January 2009