This is one of the key takeaways in Rabobank’s H2 Global Aquaculture Update, which was published this week, although the report’s lead author believes that the longer term prospects are more positive.

The report, which comes with the ominous title “On the brink of recession”, warns of weaker demand for seafood compared to both the proceeding six-month periods, coupled with an increase in shrimp production leading to a significant drop in prices. When combined with the ongoing high feed, freight and energy costs, many farmers – especially shrimp farmers – are likely to struggle, it predicts.

Rabobank expects demand and prices to decrease in H2 © Rabobank

Concerns in the shrimp sector

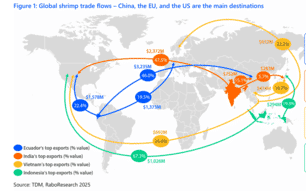

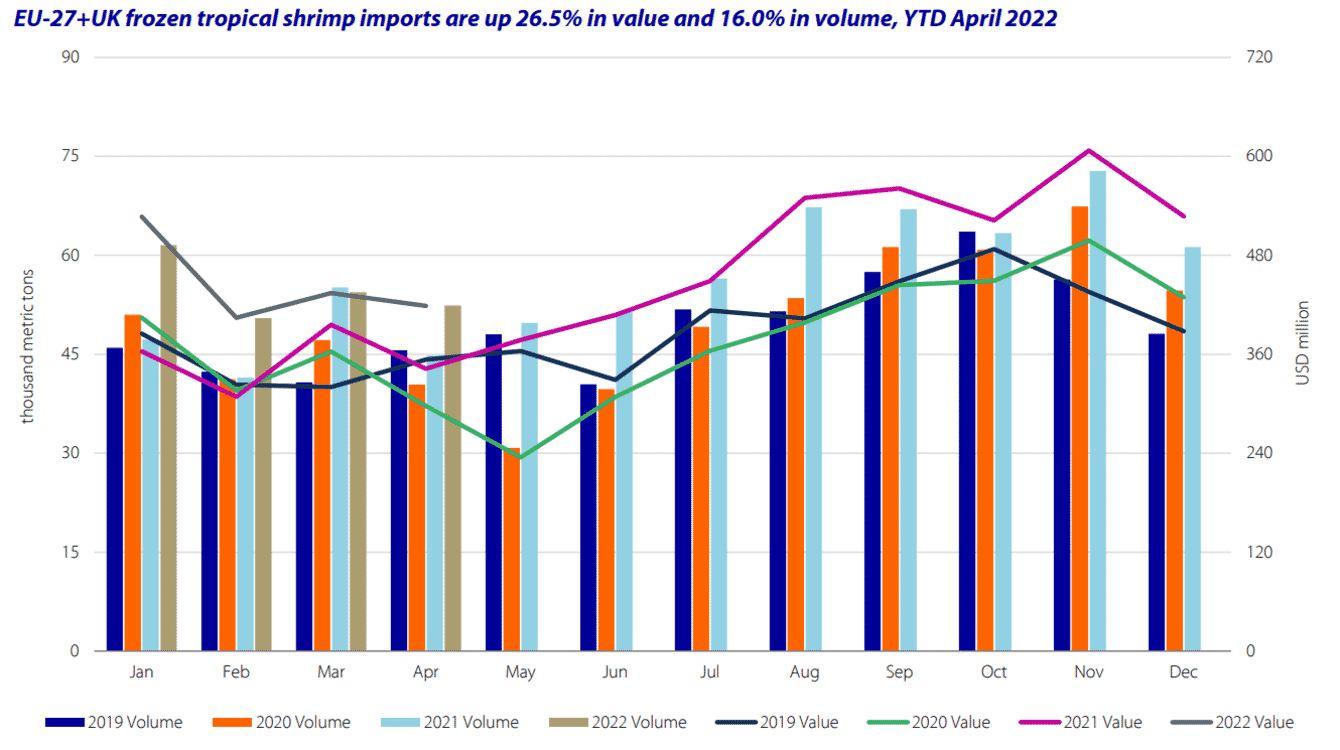

While the US and EU drove shrimp demand in 2021 and the early part of 2022, demand is likely to cool off in the remainder of the year, especially in food service, as inflation has reduced disposable incomes. Meanwhile, although China’s shrimp imports have improved strongly, Covid lockdowns and import restrictions remain unpredictable, it warns.

In terms of production, the report notes that shrimp supply still has strong growth momentum Indonesia, Vietnam, and especially Ecuador, even as 1H prices have corrected and costs have increased.

“If shrimp supply continues to expand as it did in 1H or if demand further declines due to recessionary consumer behaviour, we may see prices below breakeven for farmers. In some cases, this has already occurred,” notes report’s lead author, Gorjan Nikolik.

In terms of the performances of individual countries Ecuador is continuing the remarkable growth rates seen last year.

Despite considerable price declines and a 15 percent increase in feed costs in the region, Nikolik thinks that Ecuador’s production for 2022 will reach a new record – potentially as high as 1.3 million tonnes.

An additional 35 percent in Ecuador’s shrimp production is equivalent to adding the entire of Thailand’s annual production to Ecuador’s already record 2021 production, or producing enough extra to fulfil Japan’s entire demand, Nikolik observes.

Meanwhile, Southeast Asia’s shrimp producers might be more vulnerable to the combination of a drop in demand and an increase in feed prices. As Nikolik notes, the change in feed prices has been slower to hit producers in Asia than it has in South America, so it’s very possible that these were not factored in when producers were stocking their ponds in April and May.

“Did they scale down? I expect that they were still feeling bullish when stocking their ponds in H1 – hoping to repeat the 2021 situation, when the second half of the year saw a huge growth in demand,” Nikolik suggests.

"Normalisation" in the salmon sector

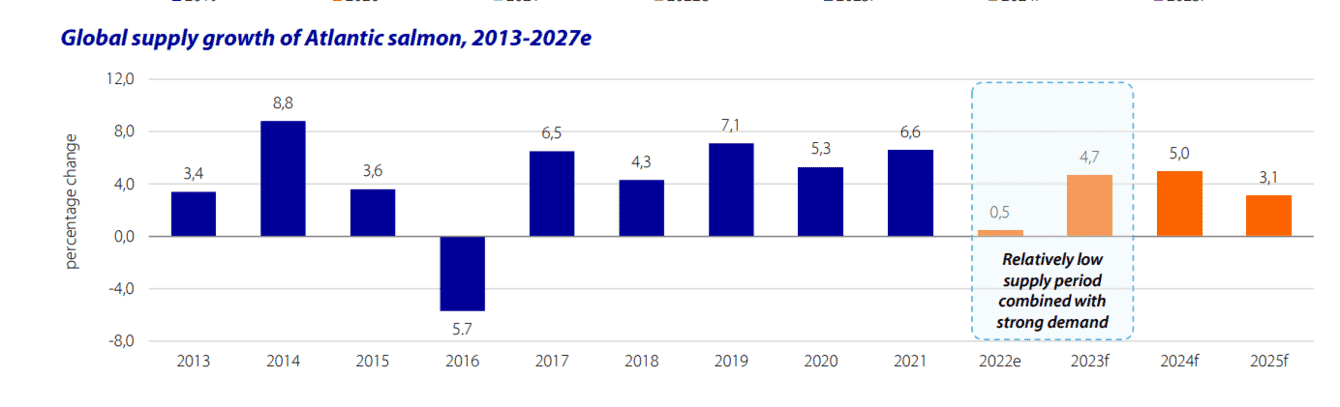

While the salmon sector is likely to see a reduction in prices during H2, Nikolik doesn’t expect this to be too drastic for producers.

“For salmon it’s more of a normalistion. H1 was so unique in terms of profits. It was a perfect storm combining the growth of food service, the overheated US economy, inflation had not yet made a major impact, and supply had fallen by 6 percent – the biggest drop since 2016 – which explains why the sector achieved unprecedented spot prices of 130-140 NOK per kg,” notes Nikolik.

“But for H2 the supply side is likely to see a 6 percent growth, demand is starting to fall in bars and restaurants in the US, inflation and the increasing feed prices will all have an impact,” he adds.

Despite this he points to the fact that contracts will mean that many companies’ fortunes will be less drastically reduced, while farmers won’t yet have been hit by the worst of the feed price hikes, as those fish being harvested now will have mainly been given feed bought at pre-inflation prices.

“The profitability of the sector will still remain strong in H2, although the cost of production per kilo of fish produced will continue to increase well into 2023, negatively impacting profitability also next year,” he predicts.

Rabobank expects an increase in supplies in H2 to cancel out the decrease seen in H1 © Rabobank

A longer-term forecast

Although the short-term outlook looks better for salmon than shrimp, Nikolik argues that, for those shrimp farmers who are able to ride the economic downturn, long-term demand prospects remain bright.

“It’s a product that has so much strength. It is loved by almost every culture globally – Americans love them and Chinese love them – and these are the world’s two largest economies. They’re easy to process, there are no bones, they’re perfectly bite-sized and they come in so many convenient forms – from salads, to dips to entrees, to dumplings. They have no fishy taste, so kids love them, old people love them, there’s no religious constraints. They’re even more popular than salmon, which is more dependent on Western culture and Western infrastructure, while shrimp is traded frozen and can stay in frozen inventory for months,” he points out.

And he notes that there’s scope to hugely increase production too.

“There are virtually no constraints on the supply side either. While salmon has serious constraints – not least the difficulty of obtaining concessions – there’s no such thing in shrimp. India alone could more than triple production to produce 3 million tonnes. If you look at Ecuador’s production for its size, think how much Brazil and Mexico – which have maybe 20 times longer coastlines – could produce if they even get close to Ecuadorian productivity,” Nikolik argues.

He also points to the much larger spread of wealth in the shrimp sector – wealth that really makes an impact given the fact that most shrimp farming occurs in developing nations.

“Think of the social impact too – it employs so many people in relatively poor regions and produces so much relative wealth for them," he adds.

As a result of these factors he believes in the long-term success of the sector.

“We expect a challenging period in the short term, but remain optimistic about the long-term prospects of the shrimp industry – it tends to be very supply elastic and can respond within a 100 days, whereas salmon takes two years to respond,” he concludes.