Fish produce a lot of ammonia, which is a waste product from their protein metabolism. Ammonia also pollutes the water in which they live, and in excessive concentrations can even be deadly.

“We humans excrete excess ammonia in our urine, through urea. Fish do so through their gills,” explains microbiologist Huub Op den Camp.

“In Nijmegen we specialise in identifying and propagating ammonia-eating bacteria such as anammox.” The gills were therefore a logical first place to start looking for nitrogen cycle bacteria in fish.

Preparing gills

The research indeed showed that the gills of both zebrafish and carp are filled with micro-organisms.

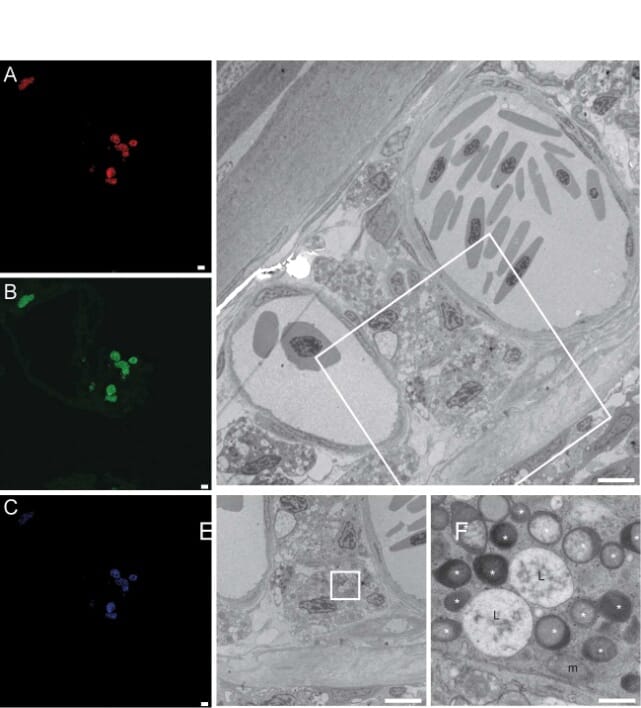

To identify these micro-organisms, microbiologists used a variety of microscopic techniques and isotope measurements, in addition to DNA finger printing.

“Preparing gills for experiments was challenging, it was much different than what we are accustomed to,” says Mike Jetten.

“The cartilage in the branchial arch makes it extremely difficult to slice thin sections for microscopic study.”

But the microbiologists ultimately succeeded: Figure 1 shows electron microscope images of the bacteria in the gill tissue.

Ultimately the biologists removed the gills from the fish for further study. Even then, they still produced nitrogen gas, which means that the bacteria remained active. The biologists also wanted to determine exactly how much ammonia the bacteria eat.

To do this, they had to determine the nitrogen balance in aquariums. This was a difficult task due to the continuous water exchange and biofilters, which also remove some ammonia. In intermittently fed fish, it turned out that 31 per cent of the feed ends up in the water as ammonia. In continuously fed fish this was only 18 per cent; much of the ammonia had been converted to nitrogen gas, which escaped harmlessly from the water.

Feeding tactics

The discovery of a new type of symbiosis does not happen very often.

“At some point during evolution, fish accepted these bacteria, which turned out to be a successful strategy,” says Op den Camp.

“The question is now whether the bacteria are also present in species other than zebrafish and carp. We suspect that this symbiosis is common in freshwater fish, but that remains to be confirmed.”

This study also provides a lesson for aquaculture. “Feeding leads to a peak in the ammonia production. For the symbiosis between fish and bacteria, it is better if the ammonia production is more constant. It is therefore better to feed often with small amounts than with large amounts once or twice a day. The bacteria – and therefore the fish – benefit from this feeding tactic. Nearly all organisms benefit from constancy.”

Environmental Microbiology Reports published an early view of the results this week.