© CSIRO

Called Supporting a strong future for Australian aquaculture, the report found that Australian aquaculture is a growing industry with a strong positive outlook, but that unlocking its full potential will require the removal of a number of barriers to growth.

The report notes that: “Australia’s aquaculture industry is small by global standards, accounting for less than 1 per cent world production. But Australia has a reputation for producing safe, sustainable, high-quality and high-value aquaculture products. The Australian aquaculture industry has many advantages over its competitors: the ability to culture a large number of species over a range of climatic zones; access to relatively inexpensive land and water; and freedom from many of the diseases that affect aquaculture in other countries.”

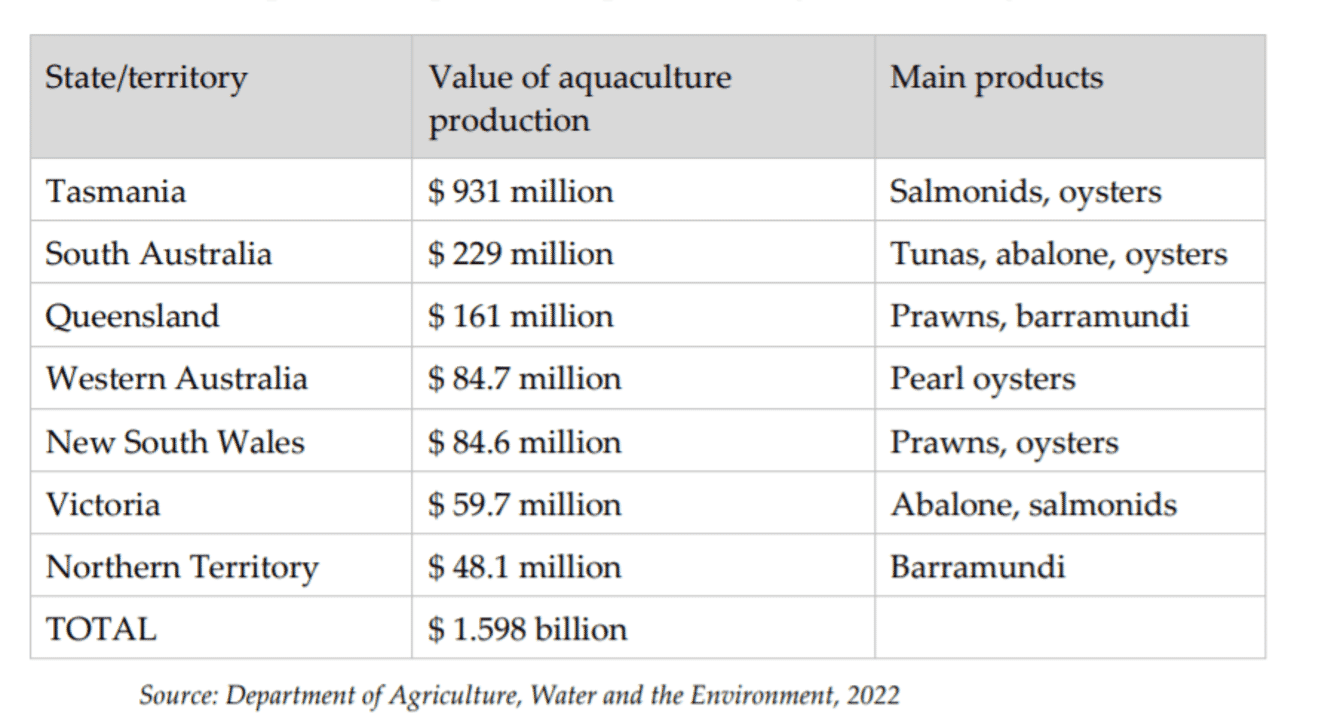

It reveals that Australian aquaculture sector production in 2019-20 was valued at $1.6 billion, an increase from $1.5 billion from the previous year. In volume terms, production reached 106,139 tonnes. By comparison, wild-catch production was valued at $1.58 billion, a decrease of 12 per cent from the previous year.

“The higher dollar value of aquacultural output was reflected in the fact that it represented 38 per cent of the total volume of production of fish but 51 per cent of total value, compared to 62 per cent and 49 per cent respectively for wild-catch production,” the report states.

The report notes that most of the value of Australian aquaculture production comes from high value species such as pearls, salmonids, tuna and oysters, but over 40 species are commercially produced. The top five aquaculture species groups, in order of production value, are: salmonids, tuna, edible oysters, pearl oysters and prawns. Other species groups include: abalone, freshwater finfish (such as barramundi, Murray cod, silver perch), brackish water or marine finfish (such as barramundi, snapper, yellowtail kingfish, mulloway, groupers), mussels, ornamental fish, marine sponges, mud crab and sea cucumber.

Committee chair, Rick Wilson MP, said: “There are many exciting opportunities for the growth of Australian aquaculture. The growth of the industry will help meet domestic demand for seafood, boost exports and provide thousands of additional jobs, especially in regional areas.”

“Innovation is a key to the expansion of output and increased domestic and global market share. The committee noted the example of offshore aquaculture. With investment in research and the development of new technology, together with appropriate regulatory changes that encourage investment, offshore aquaculture can contribute to a significant increase in total production,” he argued.

“Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS)… have many potential applications within Australia’s aquaculture sector and could play an important part in the industry’s future,” he added.

Barriers to expansion

Wilson also noted the hurdles that the industry needs to overcome – including biosecurity measures and a shortage of skilled workers in the sector.

“The issue of biosecurity and potential threats from imported disease stands out as a key issue for the industry and for regulators. Strong biosecurity regulations are imperative for the growth of aquaculture because they are a prerequisite for investor confidence, while protecting Australia’s reputation for high quality product. Responding to consumer and community concerns about environmental standards and the ecological sustainability of aquaculture needs to be a high priority, both for producers themselves and for governments,” Wilson reflected.

“Future growth in the sector also depends upon the capacity to attract and retain skilled and unskilled workers, including provision of the education and upgraded skills to manage new and innovative technologies,” he added.

Wilson also drew readers’ attention to the need for better labelling regulation.

“One of the central issues in the inquiry was the naming and labelling of seafood. The committee was made aware of flaws in standards that could cause confusion amongst Australian consumers. To cite an example, 60 per cent of Australia’s barramundi market is filled by an imported fish known internationally as Asian sea bass but sold in Australia as ‘barramundi’. Most consumers would not be aware that they are likely to be eating an imported product. The Committee therefore supports reforms to labelling standards, including labelling of imported seafood products in foodservice settings,” he observed.

Furthermore, Wilson noted the confusion caused by current rules around the country of origin labelling of seafood.

“Consumers are unable to know whether they are buying imported or Australian fish at their local fish and chip shop. Consumers have the right to know where the seafood they buy originates from. It is nonsensical that there are no country of origin labelling rules for the food service industry, and this must be addressed,” he urged.