“For many years working for Nordea was the best job in the world – I had a great degree of freedom in my role and it was very exciting. I could probably have worked there until retirement, but had got to the point where I had seen most of the issues – the sector reports and updates started to feel like they were going in a circle,” explains Giskeødegård, who was the Norwegian bank’s chief seafood analyst for 25 years.

However, amidst the increasingly familiar cyclical trends of the conventional salmon farming sector there was one part of the industry which began to catch his attention.

“In the last two of three years land-based salmon farming was emerging as the most exciting and disruptive part of the sector. I’d talked to many of the players about their plans and roles and licences,” he reflects.

The combination of the entrepreneurial spirit of the RAS pioneers and the development of disruptive new technologies that were needed to enable these systems to produce market-sized salmon appealed to Giskeødegård – and there was one company that stood out.

“It was a group of people I really believed in, including former colleagues – four from finance and four with a deep knowledge of fish farming,” he explains.

The Columbi concept

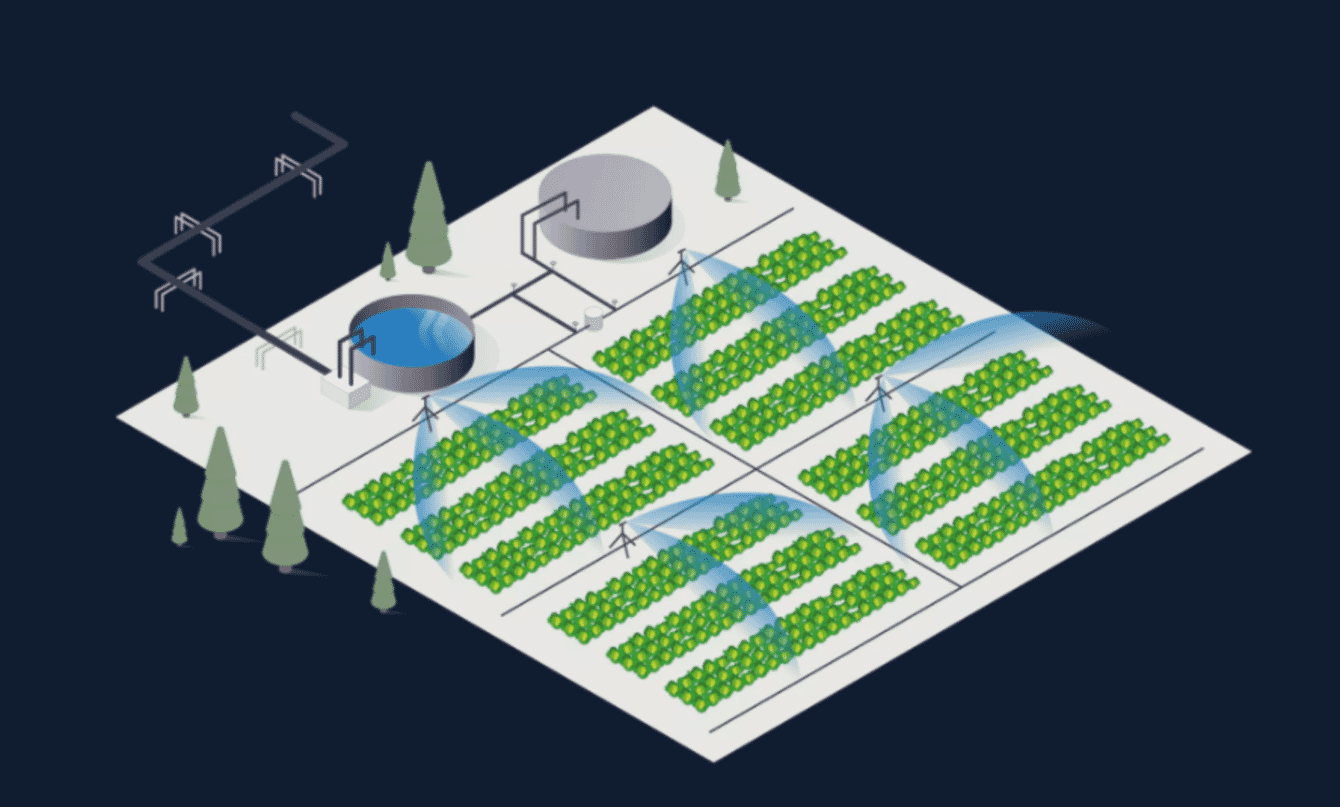

Columbi Salmon’s concept, he explains, involves much more than the standard egg-to-plate business plan of most RAS salmon producers. The circular economy is central to Columbi's philosophy, and plans for the Ostend facility include using the water from the freshwater part of the system to produce salads in an adjacent greenhouse.

“We estimate that – in the freshwater production phase – for every kilo of feed we could produce one kilo of salmon and 5-10 kg of salads,” he says.

While Giskeødegård notes that aquaponics it’s not a new concept, Columbi aims to do it differently from the bulk of the existing aquaponics systems in Europe, which are largely urban and are focused mainly on the production of greens and salads.

“The others are mainly small-scale, mainly urban, often rooftop producers,” he reflects.

In order to test the concept, Columbi is currently taking part in a trial in Norway. Called Carbon Neutral Salmon, it is a collaboration between the startup, the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), Morefish and Biomar. It involves an RAS containing 1,000 smolts and a greenhouse for salad production. It will allow a number of key data points to be assessed before Columbi finalises the design for the Ostend facility.

Turning the fish waste into biogas is another way for the facility to reduce its carbon footprint, although Columbi doesn’t plan to do this in-house.

“We will need to co-operate with a biogas producer, but in turning all our waste and dead fish into biogas we should be able to recover 20 percent of our energy consumption,” he says.

And another renewable might also help to address the facility’s carbon footprint.

“The site in Ostend will most likely have around 50,000 m2 of roof space, which would be ideal for solar and could provide another 15 percent of our energy needs – so, between biogas and solar, a third of our energy needs will be met. And 100 percent of the energy in Ostend is renewable, coming from offshore wind and biogas,” he notes, so the remaining 65 percent will be clean, green energy too.

The company is currently looking to set up a second site, in France, and is already assessing the preliminary requirements for this second phase.

© Columbi Salmon

Raising funds

According to Giskeødegård, Columbi Salmon is looking to raise a total of €180 million to establish its Ostend facility and has so far raised €30 million – 70 percent of which came from Refsnes Laks, the family-run salmon firm that co-founded the company.

“It’s a good capital base and we aim to be fully-funded in the next 12 months. The remaining €150 million will have to be raised through equity funding. Land-based startups are too immature for bank debt financing at this stage. We assume that the banks will be able to provide debt financing when we start to build biomass,” he explains.

But he appears confident that the funding will be forthcoming, a range of salmon RAS have attracted hefty investments in the past few years, and Columbi Salmon have experienced attention and interest from various investors, which bode well for the upcoming fund raising.

“We have been in dialogue with several potential investors for a 'heads-up' on our case. In the capital market, there is a window and we want to use that,” he reflects.

Despite the fledgling state of the salmon RAS sector and the well documented issues of its frontrunner, Atlantic Sapphire, Giskeødegård believes that investment will continue apace, for the time being at least.

“The RAS sector is much more robust than I thought it would be. Two or three years ago we thought that if frontrunners like Atlantic Sapphire started to lose fish then it could be all over for RAS. But the company has now had several mortality incidents and, while it makes investors aware of the risks, it has not taken away the optimism. They see that Atlantic Sapphire is the first mover, we can go in higher up the learning curve and not make the same mistakes,” he reflects.

Giskeødegård also points out that, while the mortality incidents in RAS might sound stark, they are not as terrible as they look at first site.

“If you have one major mortality incident a year in an RAS, you may lose 10-15 percent of your biomass. This is of course dramatic. But other mortality is normally lower that farming in sea. In Norway, total loss of 15-20 percent over a life cycle has been the average over the past years. The numbers are not that different, just that at sea it’s a much more gradual process and not as dramatic,” he notes.

A recipe for success

As well as learning from the mistakes of others, Giskeødegård believes that there are two main criteria to bear in mind to be successful in RAS production.

“You need a strong and flexible design for your facility and you need the right people on the ground in case there are issues, for example if nitrogen levels suddenly go up, you need people who can respond quickly and effectively,” he reflects.

In terms of finding the right personnel, Giskeødegård believes that the company’s connection to the Norwegian salmon farming sector should help them hire talented people, while the Ostend location will also be favourable.

“In the first phase we will need key personnel from Norway, but Ostend is also close to the universities in Ghent and Boulogne, which include technical training courses with a focus on the blue economy,” he reflects.

Long-term ambitions

It’s early days, but Columbi has a vision for what it would like to achieve in the course of the next decade.

“We’d like to be producing 50,000 to 80,000 tonnes of salmon over several sites in Northwest Europe and be established as one of the leading sustainability-focused seafood companies in Europe,” Giskeødegård reveals.

He also believes that Columbi’s production model, and the fact that their first site is still to be built, will allow them to tailor their facilities to meet the demands of an emerging generation of consumers.

“With a blank sheet we can start building the demands of our consumers into our design,” he explains.

However, he is also aware of the need to develop a system that makes economical as well as ethical sense.

“While many people want to build an ultimate green dream, in the end it is important to do what is practical and it needs to be economically sustainable as well as environmentally sustainable – we need to strike the right balance,” he emphasises.

The bigger picture

Given Giskeødegård’s former role at Nordea, it seems rude not to ask him two of the key questions that are never far from the minds of all those with an interest in RAS.

“In terms of production costs at Columbi, our preliminary forecast is in the high 40s NOK per kilo, which is slightly higher than the current average production cost of salmon at sea. But we will have lower transport costs, no import duties to reach the EU market and we won’t have to pay a levy to the Norwegian Seafood Council. This will reduce the cost by at least 3 NOK per kilo, and would bring us very close to cost parity with conventional production,” he explains.

“And we will also be able to reach the market 3-4 days quicker than a salmon producer in northern Norway, for example, which will give our salmon a longer shelf life,” he adds.

And, as for his forecast for the trajectory of the global salmon RAS sector, in volume terms?

“There will probably be lower volumes than consensus in the market is anticipating in the next 7-8 years, but then greater volumes than anticipated after that – that tends to be the way with emerging technologies,” he says.

“So, shooting from the hip, I’d say that there will be around 100,000 tonnes of salmon produced annually in RAS in five years’ time, up to 600,000 tonnes in 10 years and between one million and 1.5 million tonnes within 20 years,” he predicts.

Which of the multitude of emerging startups in this increasingly crowded field will be responsible for the bulk of this production remains to be seen. But the arrival of rational industry veterans such as Giskeødegård on the scene suggests that either lockdown is taking its toll on the collective sanity of the seafood sector, or that the time really has come to grow meaningful volumes of salmon on land.