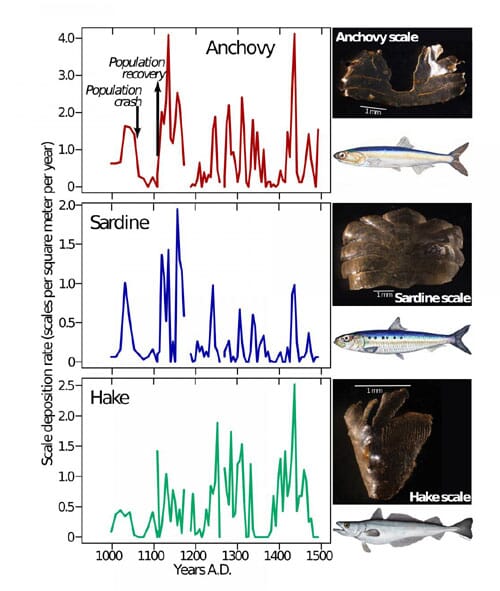

Natural population fluctuations in Pacific sardine, northern anchovy and Pacific hake off California have been so common that the species were in collapsed condition 29 to 40 per cent of the time over the 500-year period from A.D. 1000 to 1500, according to the study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Using a long time series of fish-scales deposited in low-oxygen offshore sedimentary environments off southern California, the authors from NOAA Fisheries and the University of Michigan described such collapses as "an intrinsic property of some forage fish populations that should be expected, just as droughts are expected in an arid climate."

The findings have implications for the ecosystem, as well as fishermen and fisheries managers, who have witnessed several booms, followed by crashes every one to two decades on average and lasting a decade or more, the scientists wrote. Collapses in forage fish can reverberate through the marine food web, possibly causing prey limitation among predators such as sea lions and sea birds.

"Forage fish populations are resilient over the long term, which is how they come back from such steep collapses over and over again," said Sam McClatchie, supervisory oceanographer at NOAA Fisheries' Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, California. "That doesn't change the fact that these species may remain at very low levels for periods long enough to have very real consequences for the people and wildlife who count on them."

Downturns in sardine and anchovy linked to changing ocean conditions have contributed to the localized stranding of thousands of California sea lion pups in recent years.

Looking back in time

Scientists traced the historic abundance of sardine, anchovy and hake by examining deposits of their scales collected on the floor of the Santa Barbara Channel from A.D. 1000 to 1500. While previous studies had shown that forage fish exhibited collapses prior to commercial fishing, the new research used methods developed by climatologists to examine the frequency and duration of the fluctuations in finer detail.

"The Mediterranean climate of California with wet winters and dry summers produces a sediment layer we can pull apart like pages in a book," says Ingrid Hendy, Associate Professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. "Although these sediments have been studied before, we are using new technology to examine them in unprecedented detail."

The scientists described a collapse as a drop below 10 per cent of the average peak in fish populations, as estimated from the paleorecord. Anchovy took an average of eight years to recover from a collapse, while sardine and hake took an average of 22 years.

The record also showed that sardines and anchovy fluctuated synchronously over the 500 year study period. Combined collapses may compound the impact on predators and the fishery, the scientists said. The finding runs counter to suggestions that the two species' cycles alternate.

Variable fishing responds to change

Sardines and anchovy have at times been the most heavily harvested fish off Southern California in terms of volume. Hake, also known as Pacific whiting, spawn off California but are harvested in large volumes off the Pacific Northwest and Canada. The new study concludes these forage fish are well-suited to variable fishing rates that target the species in times of abundance, "while recognizing that mean persistence of fishable populations is one to two decades, and that switching to other target species will become a necessity."

Collapses last, on average, "too long for the industry to simply wait out the return of the forage fish."

The study authors concluded that "well-designed reserve thresholds" and adjustable harvest rates help protect the forage species, the fishery and non-human predators for the long term. However, they added that "reserve thresholds only protect the seed stock for recovery, and cannot prevent collapses from occurring."