India’s cultured shrimp exports have been growing at ~30% per annum at times since 2010, yet only 9% of suitable brackish water is being utilized. Are such growth rates set to continue?

India does indeed have substantial capacity to continue to expand production. There are new areas to develop for shrimp farming in every state, including the main production area Antra Pradesh. The west coast, in particular, has many untapped hectares which can be committed to shrimp farming; in the north, the West Bengal region can become an even larger producer; and there are also options in the southern part of India, where three harvests per year are possible.

Secondly, we should consider the extensive nature of most operations. The most intensive farms in India stock 50-75 shrimp per m2, which is only half of the stocking density used in China or Thailand. However, many parts in the east and north stock at densities as low as 5-25 per m2. With investment and training, even without new areas devoted to shrimp farming, production can increase in these regions.

Recently the WWF called for the intensification of shrimp production, claiming it can yield better environmental and economic results. Do you think this is the case in India?

At the moment, there is a diversity of intensity in shrimp production systems, both globally and within regions. I do not think that we can say that intensification automatically leads to lower or higher disease risk.

In India, I understand from conversions with local players that the relatively low density is a tool to mitigate disease risk. But with more knowledge at farm level, appropriate legislation and investment in technology, intensification can be achieved without increasing disease risks or negative environmental impacts.

The key, however, is not to rush towards more intensive production systems without fully understanding the effect on the shrimp and the water conditions. Previously in India there wasn’t a consistent blueprint to accommodate more intensive systems, but the industry is more developed today.

What are the main limits on the growth of the industry?

We have two main concerns when it comes to growth of the sector in India. The first depends on how well the industry deals with disease issues as the sector becomes more mature and a greater density of shrimp farms develops.

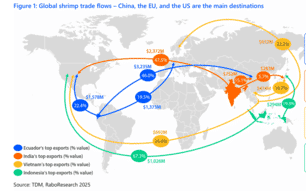

The second relates to whether the industry can deal with a potential downturn in price. Inevitably, as with all agro-commodities, the shrimp sector will experience a price decline at some point in the future. This could be due to a rising supply somewhere else in the world – perhaps from Thailand, China, Indonesia, Brazil or even a new producer such as Australia. When this occurs some farmers globally will not be competitive and be forced to reduce their shrimp production, therefore balancing the market.

Our expectations are that the Indian shrimp industry would remain competitive and profitable even in a downturn, but we do not have accurate cost data to analyse. Also, given the changing disease and technology landscape it would be very difficult to predict how cost competitiveness develops in the future.

What supporting sectors have the most to gain from the continued growth of India’s shrimp industry?

To accommodate the growth of the shrimp industry, both in terms of developing new regions and making existing production sites more intensive, support from the entire aquaculture value chain is needed. We have heard that here were bottlenecks with feed a few years ago, but currently this seems to be less of an issue. We have also heard of issues surrounding a lack of quality juveniles.

Another recent development has been the industry’s decision to increasingly focus on exporting more processed products, creating more value locally and increasing its competitiveness. Lastly, what is needed – not just in India but across the entire Asian shrimp industry – is a degree of consolidation to create larger, more geographically diverse, shrimp producers.

Geographical diversification is difficult in shrimp due to the different business models deployed in the key regions and the large cultural differences between them. But it can help mitigate the volatility – not just in terms of diseases, which can change a region’s competitiveness, but also in trade legislation, and other unforeseen difficulties, such as the widespread practice of slavery in the Thai fishmeal fleet.

About Gorjan

Gorjan Nikolik has been an industry analyst focusing on the global seafood sector including aquaculture, wild-catch, seafood trade and processing at Rabobank for more than a decade. He is a regular speaker on global seafood and aquaculture conferences and has published numerous research reports covering the seafood industry.