Although most private-sector aquaculture investors are focusing on the culture of highly prized carnivorous species, Filipino scientist Dr Westly Rivera Rosario and his team have been busy developing new culture methods for herbivorous marine finfish.

© Dr Westley Rosario / BFAR

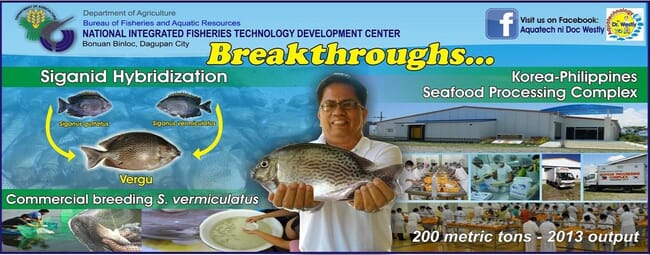

After perfecting the culture of milkfish (Chanos chanos) and creating marine-tolerant strains of tilapia (Oreochromis spp.), he and his team have now succeeded in developing a hybrid rabbitfish (Siganus spp.) with a higher growth rate and improved disease resistance.

Globally, the culture of carnivorous marine finfish and crustaceans receives the most interest from investors, with species groups like sea bass, salmon and shrimp showing double-digit growth rates. These species are enjoying high demand from western and Chinese customers and fetch relatively high prices. Their culture, however, comes with high environmental impacts. Large amounts of fishmeal are typically required as feeds, and it is estimated that, at present, a quarter of all fish landed globally – a whopping 21 million tonnes annually – are caught for the fishmeal industry.

With the planet facing a global environmental crisis, improving the sustainability of our farming methods is critical. Together with more efficient ways of farming fish, a serious part of the solution is to critically consider just which species we should be farming.

© Dr Westley Rosario / BFAR

Though it is definitely an option to develop vegetarian and lower-impact diets for farmed carnivorous species, shifting away from top predators like salmon and sea bass to herbivorous fish and shellfish seems like a far more logical solution. Bivalves, for example, require no external inputs to be farmed. Due to their massive filtration capacities, their culture actually has a positive effect on the water quality around farms. Similarly, the culture of marine herbivores has a significantly lower impact on the environment surrounding fish farms. When stocked at low densities, there is also the potential to culture herbivore finfish without external inputs. This has been common practice for the culture of carp in freshwater habitats and milkfish in backwater fishponds for centuries across South-East Asia.

Aside from lower environmental footprints, culturing marine herbivores is crucial for ensuring food security in developing countries surrounded by vast amounts of seawater – like Indonesia, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

In the Philippines, a nation of over 7,000 islands, finfish play an important role in the daily diet of people living in rural communities. With a population exceeding 100 million people in the Philippines, large amounts of fish must be produced. Since the country has limited freshwater resources but nigh-endless coastal marine areas, the country’s Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) has for years been wisely focusing on promoting the culture of marine herbivores. Its main focal point has been the culture of milkfish, with the Philippines now producing around 400,000 tonnes annually, making it the country’s top aquaculture species in terms of volume.

Dr Westly Rosario, lead scientist for BFAR’s aquaculture research station in the province of Dagupan, is one of the scientists behind the successful culture of milkfish. In recent years, however, he and his team have also seen the need to diversify the country’s aquaculture sector. For the past years, they have been putting a lot of effort in the culture of rabbitfish. Actually, as he explains, it was his father who first experimented with and saw the potential of these fish.

Rabbitfish (Siganus spp.) are medium-sized herbivorous fish native to the Indo-Pacific region, thriving in coastal areas. Some species prefer brackish-water mangrove habitats while others live in and around coral reefs. Locally known as danggit and samaral, these fish are very popular and sought-after food fish. As Dr Westly explains: “The Philippines is the top producer of wild-caught and cultured rabbitfish, with annual landings of around 30,000 tonnes. The demand for export within South-East Asia and other markets like Hawaii is very high. However, few Filipinos are raising rabbitfish due to the low supply of fingerlings and un-disseminated technology. Their popularity as food fish is leading to the decline of their numbers in the wild.”

About 10 years ago Dr Westly and his team started working to close the life cycle of these fish in captivity. Eight years ago, they successfully cultured two of the most commercially interesting candidates, the golden rabbitfish (Siganus guttatus) and the maze rabbitfish (Siganus vermiculatus), for the first time. Both species are popular food fish, growing to about 50cm with a maximum weight of 1kg for the first and 2kg for the latter. Fresh, they fetch around PHP 325 (US$6.20) per kilogram farm gate, and PHP 380 ($7.20) per kilogram retail, which in comparison is almost double the price of milkfish.

Their experimental hatchery is now achieving very reasonable survival rates of 5 percent from larvae to fry sizes in 45 days. The fry are stocked in nursery ponds and reach fingerling size in about 90 days. Fingerlings can then be further cultured in brackish-water ponds, pens or floating sea cages. In lower densities, the fish can be fed with filamentous algae, seaweed and sea grass which grow luxuriously in brackish-water ponds. However for large culture volumes, a local plant-based pellet feed that ensures good growth and survival rates been has already released by local feed producer Tateh Aquafeeds. Fish can be harvested at 250g within five or six months of culture from fingerling size.

Rabbitfish are also ideal candidates for polyculture systems as they are non-aggressive and feed mostly on filamentous algae and other vegetation. In the Philippines they are already co-cultured with both milkfish and shrimp. They have also been experimentally co-cultured with grouper, with small numbers of rabbitfish added to grouper cages to keep the floating nets relatively free of algae and seaweeds.

Dr Westly explains how, to further improve growth and survival rates, he came up with the idea of developing a hybrid between the golden rabbitfish and the maze rabbitfish. This took some trial and error as S. guttatus spawns during the first quarter of the lunar calendar, while S. vermiculatus spawns during the last quarter (as the team later found out, the hybrids will only spawn during a new moon). These findings on lunar cycles will enable rabbitfish hatcheries to maximise production year-round. These hybrids should grow better than the parent species because of hybrid vigor and show stronger disease resistance while fetching the same price in fresh fish markets. However, some questions remain on the potential of these hybrids escaping and reproducing in the wild. It is important to never let this happen.

Despite the strong foundations laid down by Dr Westly and his team, the Philippines was still producing a paltry 303 tonnes of rabbitfish through aquaculture in 2018, however this is almost 90 percent of global production, plus the figure is up 56 percent compared to the 194 tonnes produced in the country in 2017.

Still it cannot be denied that the culture of lower-trophic marine herbivores has enormous potential to feed the world’s steadily ballooning population, while simultaneously reducing the environmental footprint of the food we produce. This is a path more aquaculturists and investors should explore.