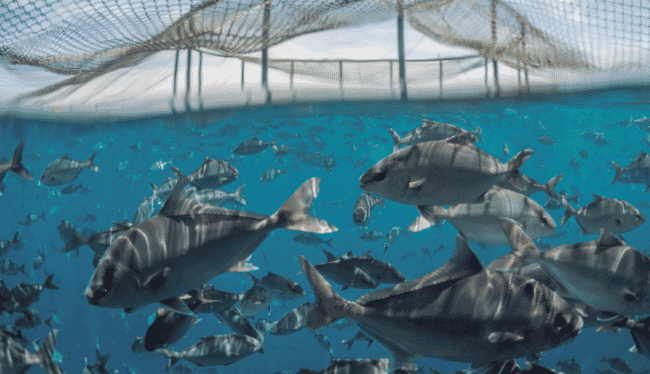

© King Kampachi, Mexico

The European Union (EU) is known and respected for its high-quality products, stringent sustainability measures and good consumer-protection standards. Its aquaculture sector accounts for around 20 percent of its overall seafood production and employs 70,000 people. But is the union putting its roe in too few baskets?

Instead of diversifying and experimenting with new species, the EU aquaculture industry is concentrating on just a few species, such as salmon, seabass, seabream and trout. This can be risky when market prices fluctuate or if species-specific diseases break out.

Increasing aquaculture diversity by investing in the culture of native fish species is a sound business solution. It can revitalise the industry while introducing more competitive and sustainable products. The Fish Site’s Jonah van Beijnen and Gregg Yan present five potentially game-changing native species for European aquaculture operators.

Groupers

Always popular and highly valued across the Mediterranean region, groupers range in size from 20cm to over 2m. They are traditionally caught wild using nets, traps and baited hooks, but rising global demand, declining natural stocks and a more sustainable mindset has forced the industry to shift from wild-caught to farmed fish.

The Mediterranean has two good grouper candidates. The dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatus) reaches 1.5m in length and tips the scales at up to 60 kg, while the smaller white grouper (E. aeneus) reaches 1.2m and weighs up to 25kg. Both are highly sought after by both commercial and game fishers as they fetch between €20 to €25 per kilogram in local fish markets, leaving wild stocks at an all-time low.

According to a recent study, landings of dusky grouper have declined by 86 percent in the past 24 years. Dusky groupers are now listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as vulnerable, while white groupers are considered near threatened.

While groupers are not yet cultured in Europe, their culture and trade is in full swing in Asia. Around a dozen grouper species are now being raised using hatchery-produced seedstock. In 2015, production peaked at 155,000 tonnes, with a total farmgate value of $630 million (Rimmer and Glamuzina 2019).

While most farmers grow groupers in marine cages, more companies are shifting to recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). A China-based company called RecircInvest Biotech, for instance, has been operating a model grouper farm since 2013. Farming Mediterranean grouper should be fairly easy, as culture protocols are similar for Asian species. The lethargic fish don’t require much space for swimming, perfect for RAS farms. Moreover, their feed conversion ratio (FCR) has, over time, been brought down to between 1 and 1.1.

A big obstacle is that Europe currently has no grouper hatcheries, though Turkey is keen to test the waters. In the past, Kilic produced over 100,000 fingerlings annually for internal growout purposes. RAS-type grouper aquaculture is definitely a great way to alleviate pressure on wild grouper stocks while catering to Mediterranean consumers.

Amberjack

Well known to game fishers, kingfish or greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili) are prized for their fighting ability and their firm pink fillets. Native to the Mediterranean, these sleek predators grow nearly 2m and can weigh as much as 80kg.

Excellent choices for sushi and sashimi, greater amberjack are raised in commercial volumes in Japan, with 38,700 tonnes produced in 2014. The species can make excellent alternatives for European seabass farmers because they grow much faster while fetching higher prices. Farms should be able to produce 6kg fish with artificial feeds in just three years, retailing at a minimum of €16 per kilogram whole.

Kingfish Zeeland is working with a closely-related cousin of this species, the yellowtail amberjack (Seriola lalandi), which grows slightly faster and is more disease-resistant, but less valued by sushi restaurants.

Though numerous European aquaculture companies have expressed interest in trying to farm greater amberjack, progress has been ponderous, with only Malta, Spain and Greece currently producing small numbers of farmed fish. This might change soon as Futuna Blue’s hatchery in southern Spain is upscaling production of greater amberjack fingerlings while also constructing its own RAS growout facility. A similar project is being planned in Alicante, about four hours south of Barcelona, with construction starting this year for a 500-tonne RAS facility.

In June 2020, an experiment conducted by the Hellenic Centre of Marine Research and Argosaronikos Fish Farms proved that greater amberjack reared in sea cages and placed in large tanks during the spawning season can mature and spawn just as readily as hormone-treated fish, paving the way for organic production. For this reason, it was one of the species selected by the EU-funded Diversify programme to bolster European aquaculture.

Both species are highly carnivorous and their culture might raise some questions on sustainability. Carnivorous species generally require the inclusion of fishmeal in their feeds, and create more waste.

With the EU’s green deal for aquaculture and Farm-to-Fork strategy currently being launched, it is crucial to focus EU aquaculture on lower-trophic herbivorous and omnivorous species. Mullet, sea cucumbers and certain seaweeds make excellent examples. All three can be combined in a polyculture and integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) approach. These species are well suited to cleaning up a considerable portion of the waste produced by the main species in cages, ponds or raceways, while generating additional revenue streams for farmers.

Mullets

Though not yet too popular with fish farmers in Europe, mullets are excellent sustainable fish choices because they are primarily herbivorous, efficiently convert food to body mass and can handle a wide variety of culture conditions, as previously explained on the The Fish Site.

Over 70 species swim worldwide, most of which have high-quality meat and eggs. A big plus is bottarga, the salted and dried roe of gravid females, which is a pricey and sought-after delicacy across the Mediterranean.

No European hatcheries currently produce mullets, while Egyptian aquaculture facilities are producing 160,000 tonnes annually. This is a shame because, as Nash and Shehadeh remarked in 1980, “Mullets have the brightest future of all marine and brackish-water finfish in the developing technology of aquaculture.”

The flathead grey mullet (Mugil cephalus) was also one of six species selected for the Diversify project, a five-year programme to advance knowledge and practical applications in the culture of new and emerging finfish species. Spinoff projects will hopefully jumpstart their commercial culture in Europe.

Sea cucumbers

Never judge a book by its cover. Sea cucumbers may be unappetising to look at, but they’re among the most valuable critters in the sea. Dried premium-grade sea cucumbers can fetch from €300 to €1,500 per kilogram.

Chinese pharmacies and restaurants covet these unassuming invertebrates for their supposed healing properties and distinct rubbery texture. Like groupers however, rising global demand has decimated many wild stocks. Sea cucumbers are typically caught using inefficient and destructive bottom trawls. They are exploited in over 70 countries, with 70 percent of wild stocks overfished, yet they are easily bred and raised. Aquaculture operators produced 90.4 million tonnes in 2012, almost equal to the 93.7 million tonnes produced by capture fisheries. As both scavengers and filter-feeders, they’re useful additions to polyculture systems stocked with fish and shrimp – becoming biologically useful and profitable value-added products.

Sea cucumber culture is well developed in Asia and Europe can definitely follow suit. One of the European groups developing protocols for sea cucumber culture is MaReSMa, which has identified Holothuria arguinensis and H. polii as the best culture candidates for the Mediterranean region.

The University of Cadiz is also working on Holothuria arguinensis, explaining how the species used to be relatively common across the Atlantic, from Portugal to the Canary Islands. As the species fetches up to €350 per kilo dried, though, populations have been decimated. Their study investigated the aquaculture potential of the species and they recorded generally good results in their experimental hatchery, noting that the density in growout was a limiting factor.

Ranching hatchery-bred juvenile sea cucumbers in the sea, through the help of local fishermen, has already been trialled across Asia and could pose a viable option for the Mediterranean as well. Besides providing an alternative income for local fishermen, the culture of lower-trophic protein sources like sea cucumbers is a great way to lower the ecological impacts of the EU’s aquaculture industry.

At the moment there are no commercial sea cucumber producers in Europe. In Saudi Arabia however, NAQUA is placing more focus on farming sea cucumber, while Blue Ventures in Madagascar has just marked the 10th anniversary of their sea cucumber farm.

© Atlantic Sea Farms

Seaweeds

Seaweeds are harvested as food for both people and livestock, while also providing useful chemical compounds like iodine. Several seaweed species are commonly harvested in Europe and are in-demand enough to be cultured commercially. About 30 million tonnes of seaweed are cultured annually, with just 1,500 tonnes of that being produced in Europe.

A recent study of the seaweed industry in Europe revealed the most important species in terms of landings and value to be Laminaria digitata, L. hyperborea and Ascophyllum nodosum. The United States sees heavy culture of sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima), which grows fast, large and has a mild and versatile flavour. Branding seems to be important to be able to penetrate consumer markets. In the USA, for example seaweeds, are sold online as Maine Coast Sea Vegetables.

Although commercial-scale monoculture seaweed farming might be difficult, farming seaweed to reduce the environmental impacts of cage-farming operations for marine finfish, while simultaneously improving the income of fish farms, has serious potential.

As presented in the recent study “Towards sustainable European seaweed value chains: a triple P perspective”, seaweeds can contribute to a circular food system in Europe, while helping transition the continent to a bio-based, low-carbon protein consumer region. As the authors note, from a “People, Planet and Profit” perspective, there is no need to focus on producing large volumes of seaweed per se. What’s needed are nature-inclusive production systems to produce just the right amount of the right seaweed species, based on the carrying capacity of European seas.

Who will step up?

Many of Europe’s native fish, invertebrates and seaweeds show serious potential for the much-needed diversification of Europe’s aquaculture sector – including freshwater pike-perch, red mullet, Mediterranean red snapper, wreckfish and even Atlantic bluefin tuna.

By trying these native species and diversifying its product base, the EU aquaculture industry can bolster its competitiveness in the global seafood market and make its domestic production more resilient and self-sufficient.

All that’s needed is for a few brave players to step up. The Chinese, among the world’s oldest fish farmers, have a saying: “Don’t be afraid to grow slowly. Be afraid of never growing.”