The first farmed Pacific yellowtail kingfish to be commercially produced in Europe is due to be available this autumn. Farmed in a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) in the Netherlands by Kingfish Zeeland, the availability of fresh Seriola lalandi could mark a new chapter in European aquaculture and inspire fresh hope that land-based production can be economically viable.

“It was in a previous role, when I was working as a VP in business development for a private investment company,” recalls Kingfish Zeeland CEO Ohad Maiman, “that I developed an obsession with land-based farming, having conducted a feasibility study into a land-based venture.”

“While the numbers didn’t add up in the operation we were considering,” he continues, “the concept of land-based fish production resonated with me – it reminded me of the growth of greenhouse technology in the ’90s.”

As Ohad explains, while it wouldn’t make commercial sense to grow huge volumes of wheat in greenhouses, high-end hydroponics and organic fruit and vegetable production has since done well in such units and he sees parallels between these systems and aquaculture using RASs. However, he was also painfully aware that the majority of land-based aquaculture ventures had lost money.

“The next step for me was to investigate why so many land-based fish production ventures had failed,” Ohad continues.

And, after poring over the history of scores of unsuccessful land-based operations, he identified three main factors that contributed to their downfall.

“Firstly, too many operators were farming the wrong species in the wrong locations – producing low-value species like tilapia and catfish in RAS systems makes no sense. So we decided to borrow a page from the Teslaplaybook and thought we should start with the highest-value species possible,” he explains.

Kingfish – which are highly prized by sashimi lovers in particular – was identified as being a suitable candidate, but to ensure that the product appealed to as many high-end consumers as possible, he felt that it was essential to emphasise its sustainability as well as its quality.

“Although a recent EU report suggested that only 15 percent of seafood consumers care about the provenance of their fish, we figured this percentage would be higher amongst consumers of premium products,” explains Ohad. “So, to ensure a premium product we decided to power the facility purely on renewables, avoid using antibiotics or chemical treatments and utilise only organic feeds that include a sustainable marine component (trimmings from fish processing).”

He also identified that growing a saltwater species could be an advantage, due to the fact that fewer restrictions are placed on the use of this plentiful resource, and that having large volumes at their disposal should lead to a radical rethink in the design of the RAS.

“The second key consideration relates to the design of the land-based facility. Freshwater RAS systems tend to have access to a limited amount of water, and therefore aim to minimise their exchange rate. However, as we’re using seawater, which is so plentiful, we have opted to go for as high an exchange rate a possible, in order to keep the fish as healthy as possible – fish health is crucial,” he continues.

“The third factor we noticed was a trend towards mismanagement,” says Ohad, “largely due to the fact that most of these ventures were established from the ground up – with most of them being run from a farmer’s perspective rather than a business developer’s one, leading to poor CAPEX and OPEX performance. As a result, we have had a CFO involved from the start and have paid as much attention to business as to biological planning.”

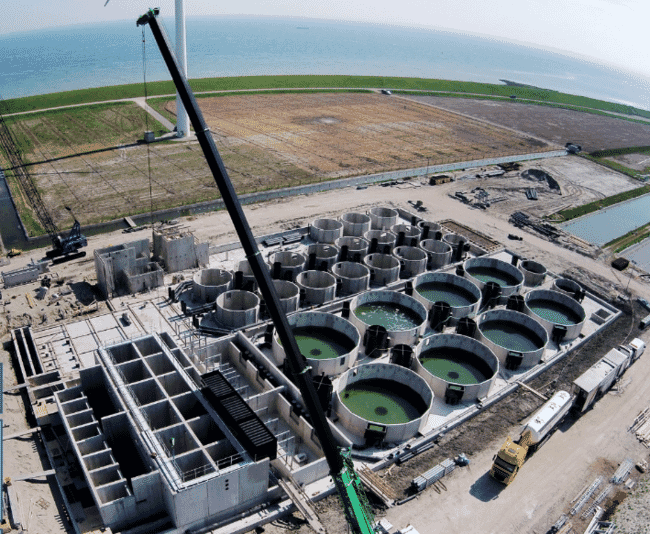

Now, three years after Ohad first devised his formula, the company has two production sites. While the principle one is still under construction, they managed to snap up a smaller-scale site nearby in order to speed up the production of their first batch of yellowtail.

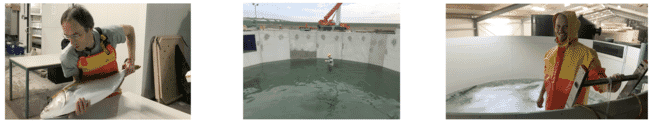

“We bought a site next to our main one that had been producing oysters using RAS,” Ohad explains, “and this enabled us to hit the ground running and will allow us to introduce the product to the market before we start producing large volumes. We should have our first few tonnes available by October of this year.”

Most of this, Ohad adds, will be destined for suppliers of high-end restaurants in Europe, although he is planning to set aside a quantity with which to test the US market too.

“We are keen to gauge the US market as, in the long run, we would like to set up another production facility in the States,” Ohad reveals.

Yellowtail may not be a species new to aquaculture – they are currently grown in marine net pens in Australia and Japan, while one other European venture, called Sashimi Royal (in Denmark), is looking to grow them in land-based systems akin to those used by Zeeland. However, the actual production process itself is by no means straightforward, especially as Ohad plans to grow his fish right through from eggs to market size.

“The more expensive a fish – in general – the harder it is to farm,” he reflects, “and we think kingfish is probably two to four times more demanding than salmon to grow, with much higher exchange rates [of water, oxygen and CO2] needed than for other species farmed in RAS. While we’ve used similar equipment to that used in RAS salmon farms, it all has to be on turbo mode – the design requirements and associated cost levels are much higher than for salmon.”

Kingfish Zeeland is basing its proprietary first-hand growth assumptions on its partner Kees Kloet’s previous pilot experience at Silt Farm – to date still the only RAS facility to successfully complete several grow-out cycles with yellowtail – and has recently made a promising breakthrough.

“We weaned our first batch of fingerlings onto dry feed yesterday, so it seems our hatchery manager must have listened in class,” jokes Ohad.

When both sites are up-and-running, they will employ 15 people directly, as well as help generate business for a number of local service providers, and there may well be scope for these figures to grow over time.

“The [former oyster] site will enable us to produce around 50 tonnes a year, while the main site will have the capacity to grow 600 tonnes annually – rising to 2,000 tonnes when the project enters its second phase,” says Ohad.

Such an ambitious project, has clearly not come cheap, but has been backed by a selection of “high-net-worth individuals”, says Ohad, as well as benefitting from support from the company’s local bank.

“We approached 16 banks for funding, but Rabobank was the only one with the vision required to venture into an RAS operation. Such investments are important to help develop the next frontier of aquaculture,” Ohad reflects.

As Ohad is aware, producing market-sized fish in RAS systems is challenging from both a biological and financial perspective. What’s more, attempts to diversify the aquaculture industry in northern Europe have also met with mixed results. However, at a time when niche high-end food products are thriving in Europe and beyond, if his business insights can be combined with the biological know-how of those involved in the farming side, there may be scope for commercial success.