Every year, aquaculture increases its contribution to global seafood production. The sector generated 110.2 million tonnes in 2016, valued at US $243.5 billion and constituting 53 per cent of world seafood supply. According to FAO data, 90 per cent of production volume was produced in Asia. To maximise investment growth while minimising ecological impacts, it pays to identify and analyse upcoming opportunities.

© FAO

Western approaches

The growing middle-class in China, India and other developing nations is boosting demand for higher-value western seafood such as Atlantic salmon – traditionally farmed or caught wild in colder regions. China, in particular, is becoming a major salmon importer, with 70,000 tonnes of salmonids consumed yearly, mostly imported from Chile, Denmark and Norway. To reduce import dependence and prices, Chinese farmers are attempting to raise salmon and other temperate fish like trout.

Among the most ambitious salmonid projects is a US $143.9 million farm currently operating in the Yellow Sea using a 30-metre high and 180-metre wide cage. This is the world’s largest submersible cage and can change depth from four to 50 metres for optimal temperature. Operator Wanzefeng Fishery aims to produce 1,600 tonnes of salmon by 2020, with plans to eventually upscale production to 20,000 tonnes yearly. Another government-backed farm aims to annually produce 20,000 tonnes in an inland recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) facility in Ningbo, eastern China.

There are ever-growing opportunities for collaboration as many of these projects are conducted with the aid of European aquaculture experts and technology providers. Chinese companies are also considering making direct investments in foreign salmon producers, with distribution and marketing eyed as priorities. This makes sense since China is poised to be the world’s top salmon consumer.

Smarter shrimp farms

Southeast Asian shrimp farming has had mixed fortunes in recent years after growing from less than a million tonnes in 1995, to 7.8 million tonnes by 2016. Unfortunately, traditional shrimp farms are among the most destructive to brackish water and marine ecosystems, particularly mangrove forests.

© Gregg Yan / Best Alternatives

An increasingly popular solution is to grow shrimp using recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) techniques. In Thailand, Charoen Pokphand Foods is looking to produce all its whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) in indoor RAS by 2023, dramatically reducing both water consumption and pollution while minimising the risk of diseases which typically come with water pumped in from nearby rivers.

According to CP Foods executive vice-president Premsak Wanuchsoontorn: “In the future, shrimp farms will be more dependent on automation to save man-hours and reduce water contamination.”

More Asian shrimp firms are following suit, realising that RAS, along with automation, can raise yields.

Canadian technology provider XpertSea, on the other hand, is pioneering AI-led facility management systems to optimize production, reduce disease outbreaks and reliably meet production dates. The system uses optics and machine learning. “This is a new concept which has the potential to unlock significant yields for shrimp and fish farmers. It’s about making more with less,” notes CEO Valeria Robitaille.

More advances in technology aim to make shrimp farmers more profitable while controlling impacts.

The rise of the carnivores

Formerly dominated by low-trophic herbivorous fish like carp, which thrive on algae and plants, aquaculture in Asia continues to move towards the intensive farming of higher-value carnivores like shrimp, grouper and tuna, as well as salmon, according to FAO statistics.

Though usually more profitable, these predators also have higher feed conversion ratios, ranging from about 2:1 for salmon (meaning two kilograms of fish meal is used to add a kilogram of weight) to upwards of 18:1 for bluefin tuna.

This means that instead of simply augmenting global seafood production, these forms of aquaculture may continue to eat into wild seafood stocks, since low-value pelagic species – loosely-termed as trash fish – are continuously needed to sustain farmed stocks of high-value predators. With wild-capture fishery volume having stalled since the late 1980s, this is a major concern because dwindling wild stocks will translate to higher feed prices.

Feeding the fish

Farming operations aim to produce the most seafood in a given volume of water in the shortest time at the least cost. The first aquaculture systems were simple ponds which could sustain herbivorous species like carps with little or no additional input and in Asia these extensive farming systems remained popular until recently. Now, however, there is a strong decline in the share of non-fed cultured seafood.

© Gregg Yan / Best Alternatives

Though the feeds for these carp are plant-based and have lower environmental footprints than fishmeal-based feeds, plant-based feeds require large tracts of land, plus significant amounts of water, fertiliser and fuel for processing and transport. Among the plants used for herbivore feeds are rice, corn, soy, plus floating vegetation like water hyacinth and duckweed. This shift is resulting in big opportunities for feed manufacturers and companies that are developing alternative feed ingredients that come with lower environmental impact, such as yeast and algae which can synthesise omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

Other attempts to reduce dependence on trash fish for feeds are being made. A Stanford University-led study revealed that using byproducts discarded from Chinese seafood processing plants can reduce the country’s dependence on trash fish by between 30 and 70 per cent – especially when ingredients like algae or yeast are added to the mix.

Thailand’s CP Foods successfully lowered the fishmeal content of its shrimp feeds from 35 per cent to just 7 per cent as of 2017 by sourcing from a combination of seafood industry byproduct plants and certified fishmeal fisheries.

Conclusions

All these trends clearly reveal the ever-increasing environmental footprint of Asian aquaculture. With China and Southeast Asia responsible for up to 90 per cent of global production, this can be dangerous if left unchecked – but major players have realised this and are taking steps to curb their ecological impacts.

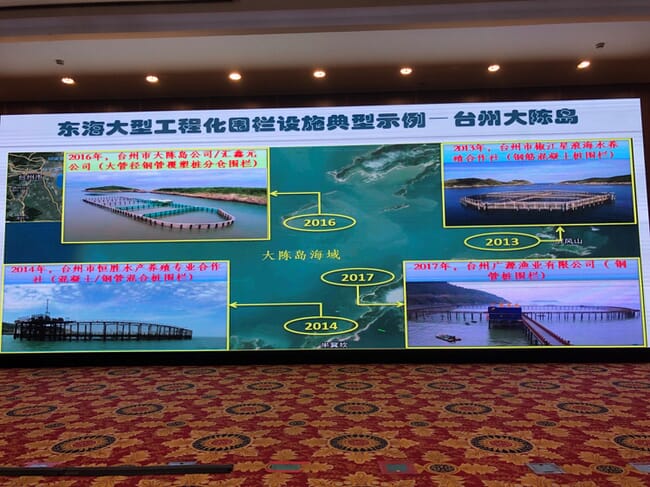

The Chinese government, for example, is attempting to shift from inland freshwater aquaculture to offshore mariculture while cracking down on illegal and polluting aquaculture operations. In a bold move, it ordered the removal of all 3,005 crab pens in eastern China’s Taihu Lake by December 2018 to protect the lake’s water quality, while also encouraging operators to shift to open-sea mariculture. Vietnam is considering the merits of extensive rather than intensive aquaculture, which produces lower seafood yields but has less impacts on both riverine and mangrove habitats.

Aquaculture is both growing and maturing. These emerging trends show how farmers, feed producers and investors can plan and prepare for the coming year.