Armed with a quarter of a century of aquaculture experience gained across four continents, he has succeeded in assembling an economically viable and environmentally friendly system that can regularly produce 4 kg/m3 of shrimp at harvest.

Here he explains to The Fish Site that it’s been quite a journey, but his patience has finally borne fruit.

Can you give a brief overview of your aquaculture experience?

I started work in aquaculture at Auburn University in 1996, where I was creating all-male populations of tilapia and catfish. I then moved on to working with the spawning of red snapper before I began work with my dissertation which involved computer controlled aeration rates, organic matter in pond soils and pond recirculation rates in relation to the response of the growth and survival of shrimp in lined ponds. After graduation, I did a brief post-doctorate fellowship at Auburn and then moved to Florida where I did a two-year post-doctorate fellowship at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, both times working with ion supplementation in freshwater to improve the growth and survival of shrimp.

I toured aquaculture projects and consulted in New Zealand and Australia during 2003-2005, before taking up a three-year position as the sole aquaculture scientist at SeaArk in South Africa. There I developed record levels of shrimp growth and biomass in large raceways and lined ponds.

I then acquired an investor and moved to Panama, where I conducted six years of research on growing a variety of species such as shrimp, the Pacific spiny lobster, koi, tilapia, reef fish, corals, oysters, a sea hare and edible saltwater plants, all in zero water exchange systems. Currently I have developed all new technology to grow shrimp and tilapia commercially in low salinity water without any expensive components or materials, and it is going just awesome!

What inspired you to establish a farm in Panama?

Panama is out of the hurricane belt, politically stable, uses the US dollar, has a well-established shrimp aquaculture industry, with readily available disease-free post-larvae and good feeds, reasonable land costs and inexpensive labour.

What have the main challenges been?

There have been many fresh challenges for this project. First the rainfall is about 2.5 meters per year and designing and building an inexpensive greenhouse ($3/m2) with just PVC and plastic, that can survive the insane rain and winds was challenging. I’ve done it, but I have to pay careful attention when I am working on the greenhouse or any of the pools – the greenhouse needs to be re-assembled perfectly or the wind and rain can make quick work of it.

Obtaining materials and equipment in a timely manner is another real problem here. Most of the time equipment has to be shipped in, as Panama does not make or sell many of the things I need. In addition, the power goes out sporadically, sometimes for 12 hours at a time. You have to have a good generator back-up. And believe me, I have developed an incredible amount of patience.

The site is 25 miles from the sea, so it took time to find the right salt compounds as well as inexpensive tests to measure the six main ions. This had to be perfect for both acclimating post-larvae as well as being adequate for growing larger shrimp. Also, I live in the mountains, about 700 metres above the sea. I knew the elevation would not be a problem in terms of temperature, as I grew shrimp this high up before, but with seawater that was hauled in from the ocean.

In addition, all systems are zero water exchange so all nitrogen you put into the tank has to be accounted for coming out. There is a balance that exists between the anaerobic and aerobic portions of the tanks that can easily be upset if it is ignored. However, I don’t think I could have ever built a more economically viable or environmentally friendly system that can regularly put out 4 kg/m3 of shrimp at harvest without any expensive components. Settleable solids are periodically taken out and added as a fertilizer for economically viable plants.

Can you give a brief overview of the sort of systems you're using?

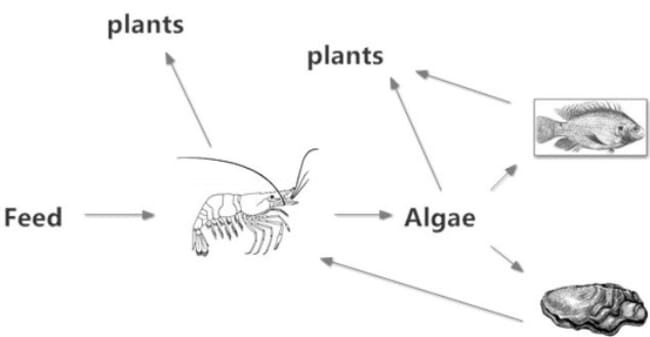

First off, the target market is all local, shipped directly to the consumer, which exactly fits the current circumstances, during the Covid-19 lockdown and quarantine. As a result, I chose above-ground pools, which are readily available and have been fitted with the previously mentioned specially designed greenhouse structures. I do not use any expensive filters, biomedia or long chain RAS components. I use gravity, natural aerobic and anaerobic processes, while occasionally manipulating carbon/nitrogen ratios through feed addition. My systems are all algae-based, which allows me to grow an equal amount of tilapia from waste algae, as the shrimp that are continually fed. Because the shrimp and tilapia all eat algae as a main component of their diets, they are a naturally anti-inflammatory food.

Shrimp are harvested as needed from pools every 1-2 weeks at 80 kg in total. Tilapia are cultured in 1 m3 floating cages within the shrimp tanks and are routinely harvested at about 1 kg each for a total of about 25 kg per cage, per year. The total cost for each individual unit, which produces about $4,000 worth of shrimp per year, is $1,200.

Where do you source your post-larvae and fingerlings from?

I source all my post-larvae from hatcheries here in Panama, which are now run by managers and staff from Ecuador. They are leasing many facilities here, due to economic complications in their own country. I have to travel about six to eight hours by car to get post-larvae regularly, which is difficult with the quarantine and you have to have papers – if you don’t you have them you can get in big trouble and papers are hard to obtain here, you have to know people. The shrimp genetics are just ok for RAS, not nearly as good as the US, while the tilapia hatcheries have sadly fallen into a bad state, as the previous tilapia hatchery manager passed away some years ago and the quality of fingerlings has deteriorated considerably.

How's the country coping with Covid-19?

Panama has gone through the strictest quarantine in the Americas during the past four months – only allowing people out of their houses for two hours, twice a week. I had to hustle to get what equipment I could while buying food. That was stressful. Luckily, I live where I work and the construction and aquaculture continued. Much of the country is still locked down, with over 25,000 active cases, mostly in Panama City. Quarantine will likely continue, as cases are developing at a rate of more than 1,000 per day, according to data posted regularly by the Minister of Health.

Shrimp aquaculture has been continuing without much interruption, as large shrimp farms and hatcheries have permission to circulate as needed, independent of day, time or area. These same conditions apply to all areas of large companies involved in agriculture – including feed manufacturing, distribution, sales and delivery. Shrimp processing is also continuing in Panama unabated. All commodity-sized shrimp grown in Panama are packaged and frozen for export, primarily to Europe.

What's the main market for your shrimp?

My market is all local. I have lived here for 10 years now and I know thousands of people through the businesses my wife and I own. We have solid reputations for offering quality service and our customer service skills are outstanding, and as such, one business easily lends itself into another. The demand so far has been overwhelming. There is a tremendous potential for a niche type market, as there are no seafood stores here where you can get quality shrimp. The local raised commodity shrimp are all for export and are all frozen with preservative added, while the large wild-caught shrimp have variable quality and irregular availability. So Panama Fresh Organic comes in with a 25 g shrimp, super fresh, delivered straight to the consumer at a great price of $7/lb and people love it. The response has been immensely positive and all shrimp are currently presold before harvest. The comments I regularly receive from my customers are “excellent”, “sweet flavour with a lobster-like taste” and “the freshest and best shrimp I have ever eaten” so I could not be happier about the progress we are currently making.

© Dr Bill McGraw

How do you fit into the wider Panamanian aquaculture sector?

Panama produces about 6,000 tons per year of commodity shrimp for export. The prototypes I have built will put out about 7 tons of 25 g shrimp per year for the first phase. There is plenty of room here to develop larger systems for phase two at the same or an alternative location. I will likely go into lined ponds, as I have contacts to get that done quickly and cheaply. We have our own tilapia broodstock and we will get a shrimp hatchery going soon with our own genetics, but it takes years to train hatchery personnel and there are no shrimp hatchery or grow-out operations here in the Chiriqui province of Panama.

What are your ambitions for the current project and where would you like it to be in five years’ time?

Panama Fresh Organic will expand as the current, chaotic Covid-19 situation allows. As climate conditions worsen, with floods destroying croplands, trade wars disrupting the accessibility of seafood and supply chains slowing certain types of food availability, smaller, more local, biosecure, totally contained and fully integrated systems will become more important.

I think people are beginning to understand the importance of a good diet. Food grown organically from algae is naturally anti-inflammatory. I have grown more than 10 different edible species in various models of these zero water exchange, algal-based systems so there are tremendous opportunities to integrate a greater diversity of plants and animals in terms of polyculture.

In five years, I see the development of a shrimp hatchery and a new line of genetics, adapted to this algal-based system. There will be further integration of computer control, with alarm signaling and feedback loops. The market will expand and become more organized – with ordering, product labeling and tracking availability through the internet.

I want to expand the permaculture section where we grow peppers, bananas, yucca, squash, pigeon pea and smaller amounts of a variety of other edible plants. The high pH, clay-based soils that are more than 50 percent rock are not good for growing much, but I have shown through many years of research, that the fertility of soils can be greatly improved with the organic input from the low salinity, zero water exchange aquaculture system waste. Everything that comes out the system is utilized and everything that goes in is accounted for.