Recently we took an in-depth look at the lack of uptake of tuna farming technology in the Mediterranean region, and what we found inspired us to investigate whether there is a commonality between the depressing status of closed-cycle tuna farming in Europe and the status of fish farming in the European Union (EU) in general.

Recent news articles suggest that aquaculture in the EU is thriving. In order to evaluate this view, we consolidated a number of production figures from a variety of reliable sources, while also having a look at the level of subsidies made available to the sector. We believe that doing so gives a clearer comparison of the costs and benefits generated by aquaculture in the EU.

To us, the outcome was rather shocking.

EU production in terms of volume and value

Consolidating production volumes by country and species from information provided in reports by FEAP and APROMAR – two reliable sources for long-term production figures – we can see that from 2008 to 2017 total finfish production in the European continent increased from almost 1.8 million to just under 2.3 million tonnes. Surprisingly, however, output by the EU member states decreased from 667,733 tonnes to 648,935 tonnes.

Although some European countries have increased their production volumes over the past decade, the major contributors to this growth – namely Norway and Turkey – are not members of the EU. For example, by far the largest contributor to the growth in European aquaculture production has been the salmon sector, which in Norway alone grew from under 900,000 tonnes in 2008 to 1.3 million tonnes in 2016. Turkey, which is also included in the European statistics provided by FEAP, increased its production of sea bream and seabass from 149,000 tonnes to 247,000 tonnes in a similar timeframe.

With respect to EU member states, finfish production is dominated by Mediterranean countries like Spain and Greece, which focus on farming gilthead sea bream and European seabass. From 2008 to 2018 production of these two species fell from 214,733 tonnes to 180,921 tonnes (within this figure there is an inclusion on 4,000 tonnes of meagre). Interestingly, at the same time, total production of these two species, from all Mediterranean countries including non-EU states, increased from 300,000 tonnes to 450,000 tonnes, largely due to growth in Turkey.

The stagnation in production does not seem to be a consequence of seed availability. In fact, during the same period (2008-2018) juvenile production of gilthead sea bream and European seabass in EU-based hatcheries increased from 740 million to 815 million fish – a 10 percent increase (APROMAR 2019). Most likely, the excess production from EU hatcheries is being sold to fish farms in North Africa as well as Gulf states, and consequently these countries reap the benefits from growing these fish out and selling the final produce.

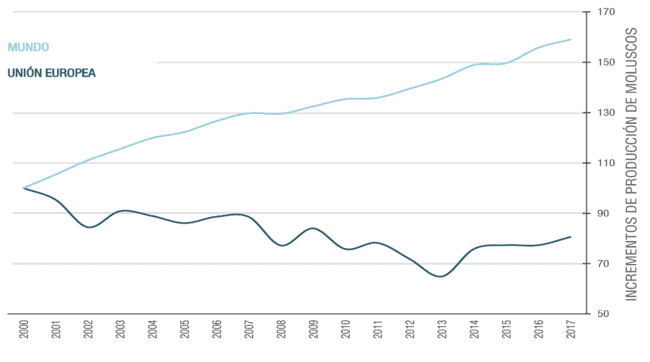

This trend in production volumes is not only true for finfish, but it is also the case for shellfish. Mollusc production in the EU has declined over the last two decades at a rate of 0.8 percent per year – from a maximum production of 826,140 tonnes in 1999 down to 621,004 tonnes by 2017.

Despite the reduction in production volume, a recent study by Guillen et al (2019) points out that the value of finfish production in the EU has increased over the past two decades, from roughly €3 billion in 2000 to €4.2 billion in 2016, which is indeed a considerable achievement. The same study highlights that, based on interviews and projections, most EU member states are expecting significant production increases in 2019 and 2020, which would finally show that the EU’s intensive support programmes of the past 20 years are starting to pay off.

However, these projections were made before the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. Plus these production increases would most likely have resulted in – at best º a recovery to 2008 production volumes.

EU support programmes

Despite this apparent limited improvement in production results, the EU continues to finance a number of programmes to drive growth in the sector – though for many who work in this sector it is unclear how much has been spent and on what.

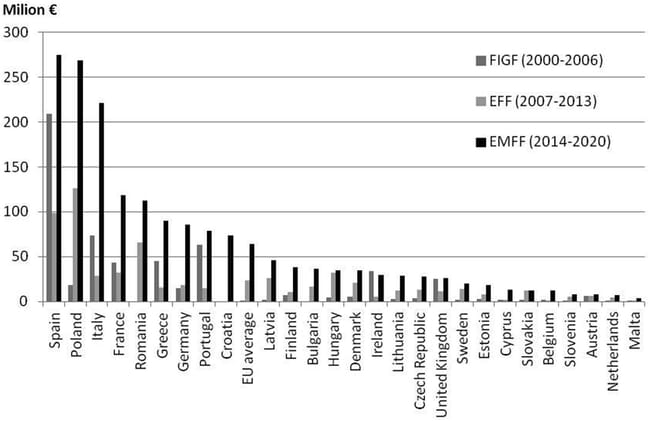

Guillen et al (2019) recently presented the first major analysis of EU aquaculture subsidies, which calculated that the EU invested €1.17 billion from its structural funds between 2000 and 2014, and is spending a further €1.72 billion between 2014 and 2020 on boosting the aquaculture sector. Taken together, these investments total €2.89 billion.

Evolution of the EU structural funds devoted to aquaculture per EU member state, as per Guillen et al (2019)

Although compared to other EU budgets this amount is not that notable, the EU aquaculture sector is not that notable in size either. Guillen and his colleagues calculated that, on average, each aquaculture company in the EU received €41,000 in public funding (2007 to 2013), and that this figure is expected to increase to a staggering €123,000 per company in the period from 2014 to 2020. As the authors point out, this corresponds to about €7,000 per employee from 2007 to 2013, and will amount to over €21,000 per employee engaged in the sector from 2014 to 2020.

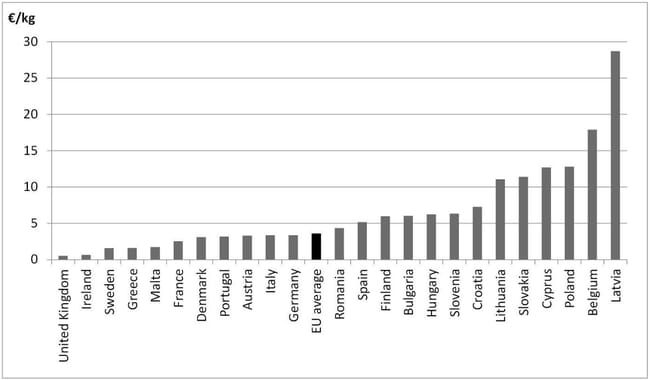

A second key finding relates to the relatively large amounts of aquaculture funding that have been heading towards Eastern Europe and former Soviet states – countries that do not really stand out for their aquaculture production. For example, after Spain it is Poland which has received most aquaculture funding from the EU during the past two decades. Also, when looking at the efficiency of EU spending in comparison to actual increases in aquaculture production, Mediterranean countries performed relatively well, while former Eastern Bloc countries – such as Lithuania, Slovakia, Poland and Latvia – performed the worst. Are these funds really being spent to drive aquaculture in Europe? Or is there some form of post-Cold War geopolitics at work?

Public funding as a projected production increase in kilogram-per-euro spend, as per Guillen et al (2019)

Costs and benefits of EU aquaculture: where do we go from here?

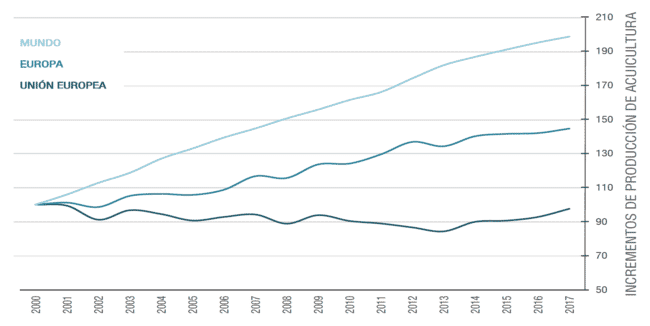

Relative to the unprecedented global growth of aquaculture output over the last 20 years, EU production volume continues to stagnate, as shown clearly in the three graphs below, from the 2019 APROMAR report. While world aquaculture output is expected to attain a 150 percent increase at least from 2000 to 2020, EU output is probably best described as flat. Based on these production figures and the analysis of outgoing subsidies, one might wonder whether these results justify the amount of public money spent, and which actions should be taken to revive the sector? Perhaps equally interesting, why do non-member states, such as Turkey and Norway, who use the same waters and target similar species and consumers, thrive while most EU member states stagnate?

Relative growth of world, European and EU total aquaculture output, starting in 2000

The Guillen paper, in line with numerous EU-associated consultants, proposes to further increase effort and subsidies towards increasing the value of EU aquaculture rather than production volume. However, it is questionable as to whether this achievement adds any benefits to the EU as a whole.

Relative growth of EU mollusc output as compared with world production

When looking to the future of EU aquaculture, there is a fundamental need to increase the volume of seafood produced in order to ensure future food security. Importing 80 percent of EU demand, as we currently do, is not sustainable and the current COVID-19 pandemic has bought this deficiency to the forefront. Relying on global supply for basic population needs, such as food, is precarious. Increasingly hostile geopolitics, climate change or the disruption of transport routes can all have a devastating effect on the nutrition intake of a population. This problem has moved to the foreground during the current pandemic, highlighting the need to increase the volume of seafood produced in the EU and thus provide opportunities to EU member states and private-sector enterprises to benefit from this production.

Equally important, the increase in value noted by Guillen et al is related to a transition from low-value species, such as carp and mussels, to high-value species, such as salmon, sea bream and seabass. Obviously this has nothing to do with reducing imports. Furthermore, moving from filter feeders and omnivores, such as mussels and carp, to high-value carnivorous species only reduces the EU drive towards sustainability, as carnivorous fish require higher-energy diets with a higher inclusion of fish oils and fishmeal.

In addition, increasing the value of the product does not generate new jobs. At present, Mediterranean member states are experiencing high unemployment rates, which are projected to increase further as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Focusing on increasing the value of aquaculture production generates little to no additional employment, while a focus on increasing production volume would.

Simply continuing to throw more money at the sector won’t solve the structural problems it is facing, as these often seem to be systemic issues that can only be addressed at the core of the bloc’s organisation. Major bottlenecks faced by aquaculture producers include the increasingly complex bureaucratic octopus that the EU system has created (specifically with regards to environmental legislation), as well as the maze of local rules and regulations that needs to be navigated. Other factors include high labour costs, the hesitance of banks to invest in EU aquaculture and general economic uncertainties. Before spending more public funds, it is perhaps advisable to prioritise, pinpoint and address the exact root causes underlying the flatlining of the EU’s aquaculture production.

In order to make this happen, more radical solutions are needed: to rethink how the EU aquaculture sector is operating and developing, and how EU subsidies are spent. Of equal importance is the need for a greater diversity of inputs in this debate, so that policy-makers in Brussels will get this job done. Finding the solution to these problems will not only benefit the aquaculture sector but will also help to keep Europe’s fragile union together and provide tangible benefits to all its member states.