The man in question, Ken Cain – a professor in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Sciences and associate director of the University of Idaho’s Aquaculture Research Institute – explains the opportunities offered by this extraordinary species of freshwater cod.

What makes burbot a promising candidate for aquaculture?

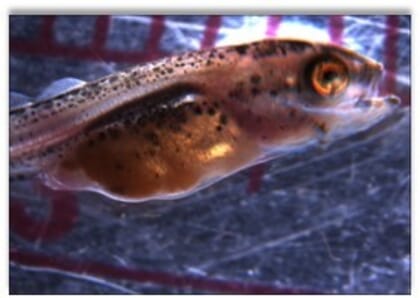

Burbot are the only species of freshwater cod and they grow well under conditions similar to species such as trout. They are also much more resistant to many of the common diseases that salmonids are susceptible to. They are great tasting and have a firm white meat fillet. In Europe, their livers are considered a delicacy and are high in vitamins and minerals, and their skin can be made into leather products. Recent taste tests have indicated that burbot are preferred over other common aquaculture species such as trout and tilapia.

Is the production protocol similar to other commercially cultured fish species?

Since they have a true larval stage, rearing this species from the egg to the juvenile stage would be very similar to marine cod and other marine species currently cultured: they all require live feed such as artemia during early rearing. However, once burbot are weaned to a commercial diet then I would say they are most similar to trout or salmon and appear to require similar water quality and temperatures and can be produced in tanks or raceways.

Why is the University of Idaho well placed to lead the development of the commercial culture of this species?

In the US, the University of Idaho has led all initial efforts to develop culture methods for this species and continues to optimise and refine spawning, early rearing, and grow out conditions. Our involvement started as part of a programme to restore and recover natural stocks in North Idaho and British Columbia. Those efforts were part of a large conservation programme led by the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho (KTOI), Idaho Fish and Game, and the BC Ministry of the Environment. KTOI now has their own burbot hatchery, but the early funding from the Kootenai Tribe and the success of these efforts (both from the aquaculture side and the restoration side) has allowed us to now address the commercial feasibility of this species. As far as I know, the only other groups that are pursuing commercial culture of burbot are in Europe, where one or two private hatcheries that provide juveniles to grow out operations have recently come on board.

© University of Idaho

What steps are required to shift the emphasis of your burbot breeding programme from one of conservation to one of production for food?

We have already taken some of these steps in our facilities on campus. The primary step was to develop a captive population of broodstock, and we now have broodstock that are from three to 10 years of age and were produced here at UI. However, since these fish have a narrow window in which they spawn (at low temperatures in the middle of winter) we are exploring methods to stimulate broodstock to spawn out of season. We know this has been successful for Atlantic cod so feel we should be able to shift the spawning period for a portion of our broodstock.

Another aspect that will be important if this species is to be commercially produced will be to scale up the breeding and early rearing programme. If commercial producers are interested in rearing this species, then juvenile production will need to be maximised and I envision that there will be a hatchery programme that would supply juveniles to grow-out facilities, similar to what is done for other species.

What sort of systems are suited to the grow-out of burbot?

For the broodstock and early rearing stages it is critical to have systems where temperature can be controlled to meet the requirements for spawning and egg incubation. Spawning and egg incubation require temperatures below 5°C and we have found that RAS with chillers work well for this. Once larvae hatch then temperatures can be increased to 10°C or higher. For grow-out of burbot from the juvenile stage (>1 g) these fish grow well at 15°C and we have produced them in circular tanks, troughs, or raceways. RAS would be fine for this, but to reduce costs these fish can be produced in flow-through facilities used for trout or other salmonids.

What are the main challenges to overcome from a production perspective?

There are likely to be a number of challenges, but we know we can produce these fish when they are reared under the appropriate conditions. We are finding that, after the first year, their feed intake and growth may slow down, but this may be overcome as this species is domesticated or selected for growth traits. Spawning and larval production will also require specific conditions to efficiently produce juveniles. If the proper systems, such as those used for marine larval production but without the need for seawater, are put in place then this can be easily overcome. The main challenge is just to get producers to start growing this fish species and begin to market it properly to the US consumer.

Do you believe there’s a market for burbot-based products – in the US and beyond?

Yes, I do. I feel that this species could be easily marketed to a range of customers and high-end restaurants. It may be a more localised market at first but if a steady supply were available then the meat, roe and other produces such as liver and even burbot skin could become available and demand a high price. There are burbot leather products such as wallets, purses, and belts made and sold in Europe from this species.

Do you think there’s the capacity to farm more burbot – both in the US and farther afield?

Absolutely! Commercial production of this species offers an opportunity to expand aquaculture in the US to an additional freshwater species. Although marine aquaculture has great potential in the US, further expansion due to regulatory restrictions is unlikely in the short term. In Canada, other agencies are working to begin culturing burbot for recovery of depleted stocks, but commercial production has the potential to work in many areas or in RAS systems where the appropriate water quality and temperatures can be provided.

© The University of Idaho

What interest/advice have you had from the commercial aquaculture/aquafeed/seafood processing sectors?

There has been much interest but these sectors have questions on the feasibility and the potential costs associated with culture of this species. We are addressing as many of these concerns as possible, but it will take a few investors or companies willing to explore this as a new species and to market it appropriately before commercial potential will be fully realised.

Do you think burbot (and other native species) can, in the long run, help to reinvigorate the US finfish farming sector?

I believe so if we can get producers (such as trout farmers) to commit to a new species and diversify their production then such additional production can only be a plus for US aquaculture. In the US, we saw a successful sturgeon caviar industry develop following early conservation efforts for white sturgeon. Burbot aquaculture could become a similar success story.

What do you think are the key barriers that need to be overcome to decrease the US seafood deficit?

Clearly, the key barriers in this area are related to cost and the need for the government to make aquaculture a priority. Substantial expansion will require us to produce more seafood in marine areas in the US. This can be done in sustainable ways. However, the cost and hurdles that are in place that prevent expansion continue to push investment to other countries where marine aquaculture has been embraced. Currently, our options are limited in the US unless we diversify freshwater products or move to RAS technologies. RAS has a lot of potential, but the jury is still out on how successful such operations can be and there will still be high demand for cheaper seafood products, which will likely continue to be imported from other countries.