Opinions vary strongly on precisely what proper welfare in aquaculture entails. Even basic principles, such as whether fish are sentient beings that can feel pain, are debated. This has limited progress, both in terms of legislation and in terms of incorporating welfare assessments and programmes across the sector. With seafood buyers and consumers demanding more transparency in terms of the products they buy; a more proactive approach is needed.

We spoke with two experts that are taking an active stance in developing solid welfare principles in aquaculture: Dr Maria Filipa Castanheira, standards coordinator at the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC), and Dr Heather Browning, lecturer on animal welfare at the University of Southampton.

Dr Browning tries to engage the aquaculture sector by publishing position papers on animal welfare. In February 2023 she published an important essay in Frontiers in Veterinary Science titled Improving welfare assessment in aquaculture.

“There remains relatively little attention given to the assessment of animal welfare within aquaculture systems. However, as the sector is growing and expanding quickly, it is crucial that animal welfare concerns are central in the development and implementation of aquaculture,” she argues. “If welfare assessments are not prioritised early on, it becomes much more difficult to adapt in future,” she adds.

Defining welfare

What exactly is welfare and how does one perform a proper welfare assessment? Collins Dictionary defines animal welfare as the protection of the health and wellbeing of animals. The health of the fish being farmed can be quantified relatively easily, by determining if the fish are disease-free and growing well. This is exactly how the first large salmon farming companies defined it for their “welfare programmes”, when they argued that lower mortality levels equate to improved welfare. However, most experts agree a more holistic approach to measuring welfare in the aquaculture sector is long overdue.

This brings us to the second half of the definition, namely determining the wellbeing of farmed fish. “With the exception of a few highly vocal critics, most experts nowadays agree that fish are sentient. This means that fish are considered capable of subjectively experiencing things through their senses,” argues Dr Browning.

This has major implications on developing solid welfare practices that take into account how animals feel. Besides physical welfare, one can – and likely should – also include the psychological wellbeing of the fish being farmed, complicating things further.

A highly diverse sector

Once the definition of welfare has been agreed upon, a set of indicators for welfare needs to be set and it needs to be determined how to measure these indicators objectively. This is a challenge because aquaculture encompasses a wide range of genera and species.

For example, while eels or catfish like to aggregate naturally and can be comfortable at very high stocking densities, this is likely not the case for solitary fish species (among others, most groupers and cobia), resulting in a need for different indicators.

Simultaneously aquaculture involves a variety of production systems, ranging from offshore cages and earthen ponds to land-based indoor recirculating systems. While most catfish would feel at home in a muddy pond, a coral grouper – which typically lives around reefs – would not.

The farmers themselves are also a very diverse group, with a wide range of resources at their disposal. So how to develop a uniform approach to welfare in such a varied sector?

Welfare assessment tools

Dr Browning explains that any strong welfare assessment should consider completeness, validity, feasibility, and setting of reasonable thresholds for acceptable welfare. But where to start as a sector?

Of the major certification labels, Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) took the lead in 2019, by developing a more comprehensive set of best practice indicators to measure welfare. A major shift is underway, as ASC’s species-specific standards will be discontinued soon, and be replaced by a single, global standard. This makes proper welfare a key requirement for all farms that apply for ASC certification and includes new criteria on handling, stunning and slaughter requirements, as well as restrictions on eyestalk ablation for shrimp. Meanwhile, antibiotic usage restrictions mirror WHO’s ‘One Health’ approach for reducing dependence on antibiotics.

Dr Maria Filipa Castanheira is ASC’s standards coordinator on fish welfare and leads the initiative.

“ASC decided to expand and broaden the current content on fish health and welfare because we consider welfare to be a key factor of sustainable production. We fully acknowledge that fish species are sentient beings, and their welfare needs to be addressed,” she explains.

To achieve this, she continues: “The initial phase of the project saw the development of a set of indicators covering fish welfare, with a focus on finfish. These indicators were created in collaboration with a technical working group of fish welfare experts. A second phase of the project followed which took ASC’s work one step further by developing a set of indicators for shrimp and cleaner fish health and welfare.”

The current draft is expected to be published for a final round of stakeholder consultation in April 2024, together with the rest of the new ASC farm standard. This consultation will be used to evaluate an appropriate transition framework for farms, which will be at least 24 months and will be confirmed in September 2024. Following approval, the new farm standard will become operational in early 2025.

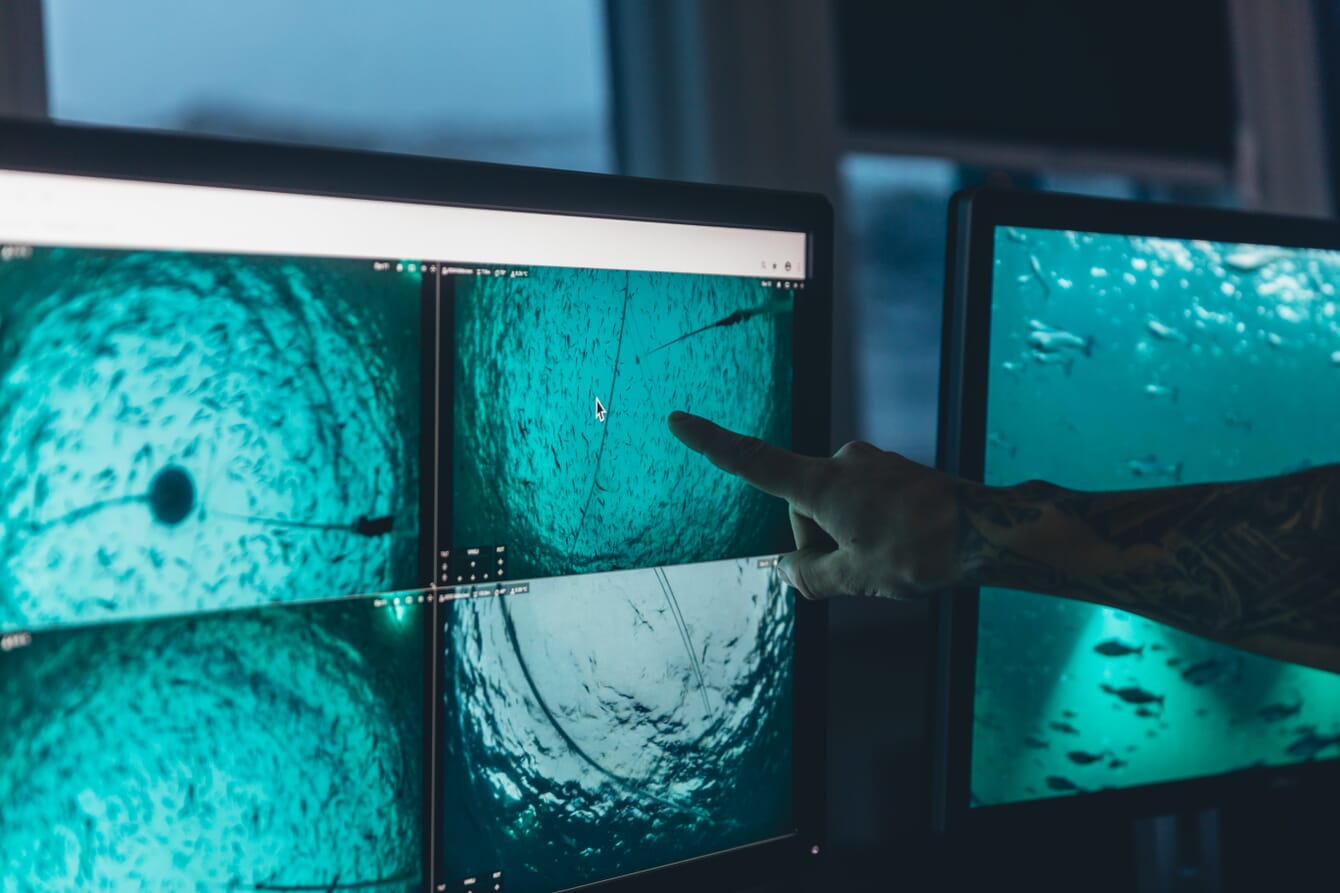

Dr Castanheira explains that ASC’s new approach will require good management practices adapted to each individual farm, as detailed in the health and welfare management plan (HWMP). This plan should always be developed and monitored by the farm, under the supervision of a qualified veterinarian. A set of indicators is specified, allowing farmers to continuously monitor and evaluate their systems and the status of their fish. The key indicators are referred to as operational welfare indicators (OWI), partly as a proxy for stocking densities, and these include water quality, morphology, behaviour and mortality.

“Examples of morphological scoring parameters include assessing eye or skin damage, deformities, and changes in colouration. Behavioural scoring and mortality are dependent on the type of species. If downward trends are observed, farmers must investigate the situation and assess their farming density and modify accordingly,” says Dr Castanheira.

Meanwhile, Dr Browning refers to most of such indicators as partial indicators. As she explains: “These assess some aspect of, or contributor to, welfare and are therefore incomplete on their own. All input measures, such as tank size or oxygen levels, are partial measures; as are many output measures, such as physiological indicators of stress, growth rate, and behavioural changes.”

She ultimately recommends using whole-animal measures, as “these use a single measure to represent the entire state of welfare for the animal. This has the obvious benefit of being a complete welfare measure, inclusive of all the external and internal states that are impacting an animal's welfare. Examples of whole-animal indicators of welfare that may work for fish include qualitative behavioural analysis (QBA), cognitive bias, laterality, and skin mucosa”. These whole-animal measures can be harder to measure and in most cases do require more training.

For those interested in the detailed science behind quantifying welfare in aquaculture and the potential for whole-animal indicators, Dr Browning has outlined a very thorough set of measures and related approaches, which you can find in her paper here. She welcomes ASC’s plans to expand their welfare assessment programme, but expresses concerns that the focus is still much more on the health than the welfare side of the equation.

The RSPCA is currently looking to improve its welfare standards for salmon

For salmon, it is the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) that leads the standardisation and certification of welfare in farming. The organisation developed a detailed standard that includes measures for the hatchery stage up to the slaughtering process. It has also been pondering on how to improve its welfare standard. Around 20 people – mostly farm managers, led by an independent academic expert – have developed 300 amendments and updates to the RSPCA’s standard and these will be released by May 2024. Among others, the updated standard will now include mandatory regular welfare outcomes assessments at both freshwater and seawater sites.

Besides the feedback on the strong focus on input measures, Dr Browning welcomes the wide range of measures on welfare in the RSPCA’s standards. However, she notes that there’s a vagueness most of these standards.

“Even where the specific certification requirements are provided, they often refer to ‘appropriate’ or ‘adequate’ conditions, or ‘minimal’ or ‘unnecessary’ stress and/or suffering, without specifying exactly what these are. There is thus a concern that this will mean different things in different contexts, lacking regularity across the industry, or that they can be set arbitrarily according to the interests of producers,” she observes.

Despite the constructive critique, the release of ASC’s new standard and the RSPCA’s updated standard will help to improve current welfare practices and help to ensure that farmers across the globe will give welfare the attention it deserves, using approaches based on the latest science. This in turn will hopefully lift the welfare status of the billions of fish annually cultured in the sector, while also helping to accommodate the current concerns of consumers.