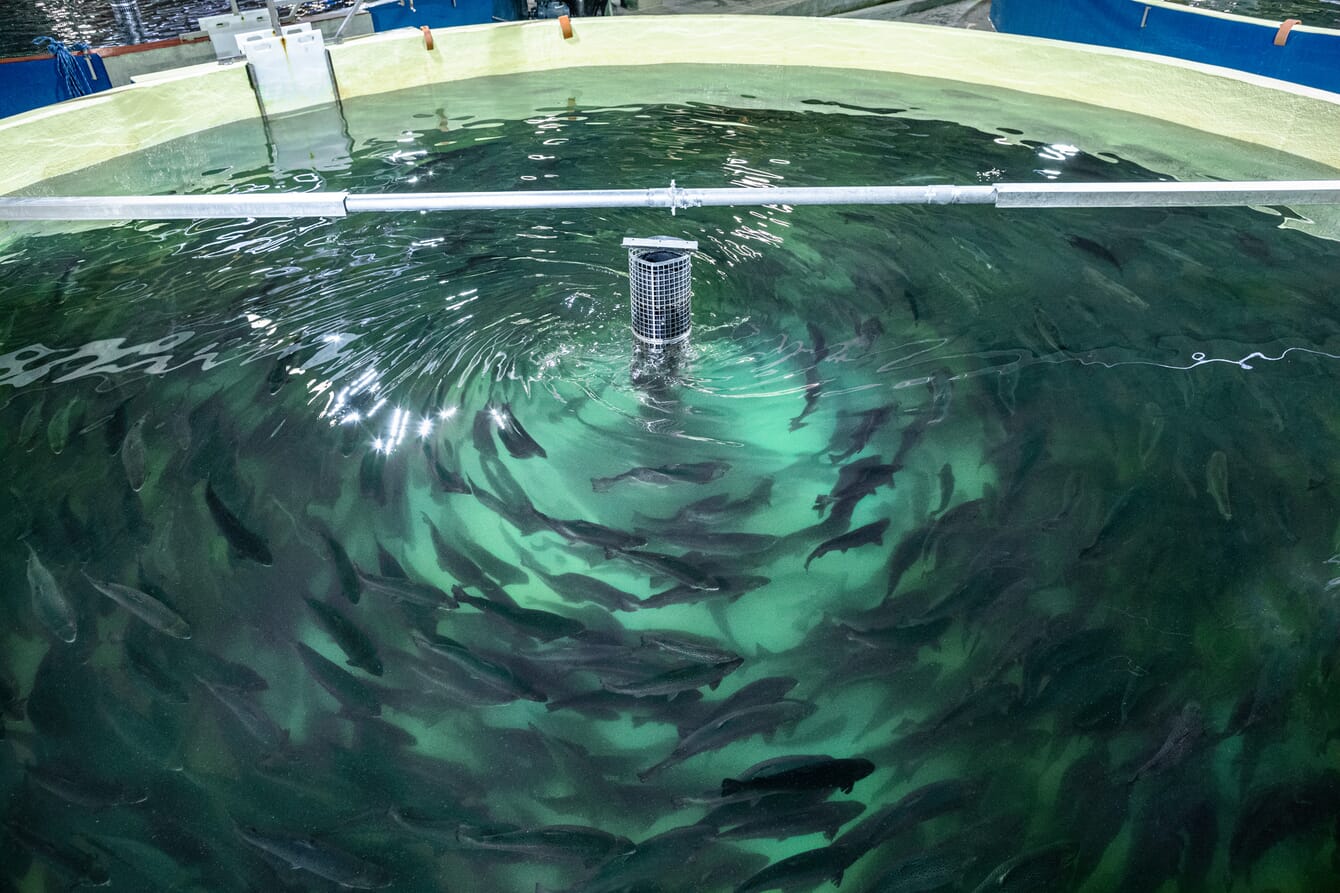

© Coppens

Recently, a Chinese friend gave me a call. His company has developed a low-cost recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) for the domestic market and something kept bothering him.

“Jonah,” he asked, “You’ve worked in aquaculture for a long time in both Asia and Europe. Can you tell me why Western RAS companies seem so successful, while in China we continue to find it challenging to create large RAS production units that are reliable and profitable?”

For years, he had read the optimistic news stories about RAS, specifically on salmon growout facilities, which made a lasting impression. Although recent headlines have hinted at challenges—including bankruptcies and halted projects—ambitious new projects keep being announced as well.

“They must have strong numbers and solid technology to back up their plans as investors keep pouring in new funding, what’s their secret sauce?” my friend asked.

Big investments, even bigger questions

Over the past decade, at least $5 billion has been invested in 150+ RAS projects, with $1.6 billion committed in the past two years alone. The majority of this capital has been directed toward large-scale (>10,000-tonne) salmon grow-out systems in the United States, Europe and the Middle East. So, how have these salmon projects performed so far?

A mixed bag of results

Concrete production figures are notably scarce and the majority of available reports refer to theoretical production capacities. Several pioneers from the early days—such as Langsand, Jurassic Salmon, and AquaBounty—have already disappeared from the scene without ever producing considerable volumes of fish. Nordic Aquafarms recently pivoted away from salmon to yellowtail kingfish, while Swiss operator Salmon Lachs has been quiet since August 2023.

One of the few remaining pioneers that is still in operation is Florida-based Atlantic Sapphire, which started out in 2010 and is considered a first mover in the sector. Its 2023 annual report lists a production volume of 1,545 tonnes, increasing to 4,400 tonnes in 2024—a 284 percent rise. However, only 670 tonnes were harvested in Q4, a traditionally strong sales quarter. The latest reported standing biomass (Q3 2024) was 2,830 tonnes, which doesn’t fully match the ambitions of the company; it aims to grow 220,000 tonnes annually by 2031. For 2025 the company expects to harvest 8,500 tonnes, which would be accompanied by its first positive EBITA of $1.50 – 2.00 per kg of fish sold. However, the catch is that the company needs another $94 million to achieve these results, which is on top of the $734 million it has secured on the stock exchange since 2018 and the $187 million in loans it has received since its inception in 2010—pretty substantial figures for a single fish farm.

Danish Salmon is another early RAS operator that has been able to survive this far. It started in 2012 and rebounded from struggles in earlier years and harvested 1,100 tonnes in 2023, reporting a gross profit of $783,000. Production increased to 2,700 tonnes in 2024, with profits expected to exceed $1.5 million. As far as I know this would make it the first company to operate a profitable salmon RAS growout system.

Meanwhile, Fish Farms in Dubai, a small but focused operator that prefers to remain under the radar, has been operating a 500-tonne capacity facility for several years now. It has been able to consistently produce fish, however at this limited scale it is hard to be profitable. Newcomers like Skagen Salmon (Denmark) and Pure Salmon (Poland) are rumoured to have promising early results, but production figures do not seem to be publicly available.

© Pure Salmon

Scaling expectations versus reality

Based on these figures, it appears that global salmon production from RAS has risen from near zero in 2020 to an estimated 15,000-20,000 tonnes in 2023 and maximum 20,000-25,000 tonnes in 2024. Some industry experts estimate that the investment made to date will translate into 25 percent of all salmon production coming from RAS facilities by 2030; up from the current 1-2 percent. Even if global salmon production from cages stagnates at the current 2.87 million tonne level, it seems highly unlikely that RAS can contribute an additional 750,000 tonnes within seven years.

To get back to my friend’s question of how these large salmon RAS farms are making money: the answer is that most of them currently aren’t. He correctly observed that making a profit from farming a rather slow-growing commodity like Atlantic salmon in a global market dominated by low-cost cage producers, is very hard. Adding the risks associated with relatively unproven technology and requiring over $100 million in infrastructure investment makes it even harder.

As Professor Caroline Engle, who has focused much of her career on the economics of aquaculture, recently noted: “Overall, the RAS models were not profitable when all costs were accounted for… substantial increases in yields of RAS would be necessary to make more efficient use of energy, water, capital, and labour resources to reduce costs to a profitable level.”

Why the investment mania continues

These limited production results and very limited proof of financial viability do not seem to have dampened the enthusiasm of investors. The main reason for this is that the global market for salmon in terms of value is expected to double in the coming 8 years from $18.09 billion to $36.31 billion; which is a lot of steaks and sushi to produce and sell!

On the supply side, wild fisheries for salmon continue to decline, while salmon cage farming operations are under severe pressure to slim down or even close their operations. Several states and provinces in North America have already put a ban on cage farming in place. Many salmon cage farms are also facing troubles from biological stresses (e.g. sea lice and diseases) and increasing seawater temperatures. With few alternative production systems available—some offshore open and closed containment concepts for salmon exist, but few have successfully demonstrated a viable proof of concept (only hybrid flow-through systems come to mind)—RAS remains the most promising—and most effectively marketed—solution for most investors.

To add to this, high-tech farming concepts like RAS, vertical farming, and aquaponics have much appeal to institutional investors looking to meet Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) goals, as it ticks all their boxes. Many investment funds are required to allocate a portion of their portfolio to sustainable projects, making RAS a relatively easy and attractive, yet misunderstood, option.

A final and perhaps uncomfortable thought is that the substantial investments required for each RAS project create lucrative opportunities for designers, builders, suppliers, consultants, marketers, and early investors—even in cases where success is never achieved. This is much the less the case with other farming concepts.

© Local Coho

Alternative investments and missed opportunities?

I think we can agree that for the billions of dollars that have been invested in salmon RAS units there is currently painfully little to show in terms of output or profitability. To put this in perspective, an offshore cage farm for your average marine finfish requires a capital expenditure of approximately $10-15 million per 1,000 tonnes of capacity. The $5 billion spent on RAS in the past decade could thus have funded offshore farming capacity of 300,000-500,000 tonnes annually. A similar investment in pond-based tilapia or pangasius farming could have increased this production capacity fourfold.

Imagine what a difference in terms of sustainability, food security and employment a $5 billion investment could have made when, for example, invested in offshore Seriola farming in the Mediterranean, or in tilapia farming using HDPE ponds with partial water recirculation in sub-Saharan Africa or South America?

However, true, this won’t solve our future salmon supply problem.

Looking ahead

While this investment comparison very much oversimplifies the situation, I believe it does underscore the ambitious nature—and perhaps unrealistic expectations—of some of the salmon RAS projects out there. That said, although it is true that RAS has made few dreams come true, I do believe change is coming. The second generation of industry players has learned valuable lessons from early pioneers and this has resulted in improved farming concepts.

As we see the first salmon RAS projects carefully succeed, the next chapter for RAS is likely to revolve around two critical questions: can these farms scale up production to a level required to provide the promised financial returns to their investors? And, more importantly, can RAS eventually transition from a niche innovation to a mainstream, replicable system, actually capable of replacing traditional cage farming?

I will explore this further in my next opinion piece, set for release next month.