Salmon stays steady

“Salmon is the safe haven of the seafood industry and has been impacted less than other sectors,” explains Nikolik.

“In Norway the forecast was for fairly limited growth – of about 3-4 percent – in the sector during 2020. Prices were very high in Q1, at over NOK 70 per kilo, and producers have benefitted from several strong years of prices, making the sector fairly resilient,” he notes.

“In Europe, which accounts for 50 percent of salmon consumption globally, most of the business lost from the foodservice sector has been taken up by retail sales. However, the decline in exports to China and the US from the pandemic has led to an oversupply in Europe and a corresponding drop in prices from almost NOK 80 in January to around NOK 54 last week. But, in historical terms, this is still a reasonable price and, importantly, it still covers the production costs,” Nikolik explains.

“While we expect prices to be lower than 2019, in Norway there have been no major disruptions in terms of feed delivery, handling and processing sectors, meaning the sector is comparatively well placed,” he adds.

“However, the situation in Chile is a bit different as its main markets for fresh salmon are the US and Brazil, while China, Russia and Japan account for the bulk of its frozen salmon sales. This meant that, during January and February, the Chilean industry was doing very well – exports to the US actually increased in February as the supply from Europe contracted – and it only started to be impacted by COVID at the end of March / early April when the lockdown restrictions hit the US and Brazil,” says Nikolik.

“More recently, however, US demand has slumped dramatically – 68 percent of the US seafood sector is food service, rather than retail, and this figure is probably around 60/40 for salmon sales, so the retail sector has not been able to make up for the disappearance of food service sales,” he explains.

As a result of this drop in demand, according to Nikolik, Chilean producers are trying to hold onto their fish until the end of this year or early next year – either by delaying harvests and reducing feeding rates to minimise growth, or by freezing those salmon they do harvest. As a result he’s expecting a reduction in Chilean salmon exports globally by as much as 30-50 percent during the peak of the crisis, from mid-March.

And, as demand drops in Russia and Japan, so the Chileans are looking to sell a higher proportion of their frozen salmon to China.

There have also been considerable disruptions to the supply chain, with some processing plants needing to be closed or modified and the cost of airfreighting salmon to the US increasing by 200-300 percent for several weeks, although that has now normalised, says Nikolik.

“Salmon is a well-financed sector, coming from years of strength, so the pandemic is unlikely to have lasting effects,” he concludes.

Shrimp shortages?

Nikolik notes that COVID-19 has had a much harsher impact on both the supply of and demand for shrimp.

“It’s been the opposite of salmon, as the shrimp sector has already been suffering from two years characterised by oversupply and falling prices, which means there’s not much of a buffer for it,” he observes.

“The start of the year saw a considerable reduction in demand from China, as the COVID restrictions coincided with Chinese New Year, and this caused producers to look to offload shrimp that had been destined for China to other markets – notably North America and Europe,” he adds.

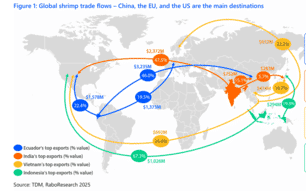

In the first two months of the year, according to Nikolik, exports to the US from India, Indonesia and Ecuador rose by 30 percent, 25 percent and 54 percent respectively.

“The drop in Chinese demand also led to producers taking a major hit in terms of prices in January and February and this was compounded by a second price correction in March and April – from below production value, to even further below production value – when demand in Europe and the US slumped due the issues with COVID in these regions,” Nikolik explains.

He also points to disruptions to the production side caused by the lockdowns – in India, for example, producers have been struggling to source seed stocks and feed, while issues in the ports mean that its harder to fulfil export deals.

“Meanwhile in Ecuador, absenteeism is having a huge effect, with up to 50 percent of the workforce in the processing, and packaging not turning up to work, despite being exempt from the lockdowns, due to fear of the virus,” Nikolik reflects.

Despite seeding rates increasing year-on-year in January and February in both Vietnam and India, by April seeding rates have dropped across the world – in some countries no seeding has taken place for weeks on end, notes Nikolik.

“If producers don’t seed soon they will miss the key June-August growing season (when production usually peaks) and we heard predictions by producers that annual shrimp production in SE Asia may be 20-50 percent lower than in 2019,” he explains.

In Ecuador, on the other hand, the larger players are planning to seed as normal, in the hope that they’ll be able to achieve high prices, despite the risk of low demand continuing should COVID-related restrictions continue in their key markets.

“Either way supply will decline quite a lot and so the inventories of (frozen) shrimp that have been stockpiled in markets such as the US, China and Europe will be consumed,” Nikolik predicts.

“It’s even possible that people will be allowed to return to restaurants before the end of the year and find that there’s no shrimp available,” he adds.

“I think there will be a major price recovery: we have already seen interesting price movements in Vietnam, when China opened its border, but – to put it in perspective – it’s still below the cost of production,” he concludes.

Brief thoughts on tilapia

Finally, he notes that China is likely to account for any growth in the markets for farmed whitefish, such as tilapia and pangasius, as its domestic seafood market recovers and it looks for alternatives to the protein previously provided by the pork sector before the outbreak of African swine fever.

“The main international tilapia trade is from China to the US. This was hit by trade war-driven tariffs during 2019, which – combined with African swine fever leaving a gap in China’s domestic protein market – led to greater domestic consumption of Chinese tilapia.”

“The US lifted its tariffs on Chinese tilapia in 2020, which led to an increase in Chinese tilapia exports to the US for the first time since 2014, but when China’s domestic market recovers as the lockdown is lifted, sales to the US are likely to decline again, due to an increase in domestic consumption,” Nikolik observes.