© Seapa

It all started with a late-night television show.

Garry Thompson, founder of Garon Plastics, was watching a segment on the struggles faced by oyster farmers in South Australia. At the time, farmers were bending extruded mesh into shape to hold oysters, but the gear wasn’t lasting. The harsh environment was unforgiving, and maintenance was a constant battle.

Mesh bags become bulky and heavy once stocked and fouled; without regular handling the oysters settle, stack and get compressed, with some lying on top of others. Left like this, shells can “print” with the mesh and deform, growth can be stunted, and sizing turns irregular because individuals don’t have even space or access to flow and feed. Periodic handling and gentle rotation breaks clumps, keeps the cohort moving so growth stays more uniform, and lets the sun and air dry off macroalgae and other fouling that would otherwise choke water flow. It’s a crucial routine, but still a labour-intensive one for most farms.

“There just was not a solution that would grow a great oyster, but also be easier on the farmer,” explains Monique Pienaar, Seapa’s marketing manager. “And Garry, who didn’t know much about oyster farming, thought: well, I know plastic – maybe I can help.”

He picked up the phone and called the farmer featured in the programme. That initial conversation sparked what would become Seapa’s founding principle: practical, co-designed solutions, developed with those who use them.

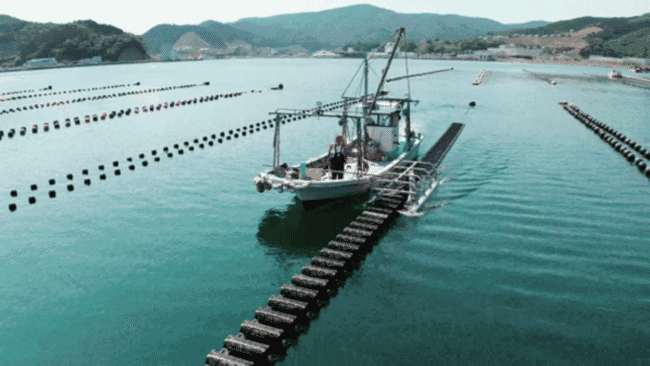

The core of Seapa’s offering is now a range of robust plastic baskets designed to securely hold oysters during their grow-out phase. These baskets are designed to be used in various growing methods and environments, long lines, subtidal, floating or drying systems. They’ve also been engineered to be flipped, rotated and handled with minimal effort.

By balancing the baskets, currents and waves help rumble the oysters around naturally. This helps break down the sharp outer shell and allows for more aesthetically pleasing - and safer to handle - rounded oysters. It also helps redirect the energy of the oyster to growing the meat, rather than the shell, resulting in a generally higher meat to shell ratio.

Australia’s challenging and differentiated oyster farming environment – marked by high energy waters in Tasmania, isolated sites in South Australia and estuaries or river based environments in New South Wales – shaped Seapa’s design. Right from the start the goal was to allow farmers to grow a better oyster, while addressing core challenges such as labour intensity.

© Seapa

“The systems were developed with the farmers,” explains Pienaar, “to reduce the manual handling and create more consistency in growth.”

Reducing the physicality of farming makes it more accessible to older workers, women and others who might not have considered it before. And for younger generations seeking more purpose-driven, innovative jobs, the cleaner, more ergonomic systems are a welcome upgrade.

"It’s not just about efficiency," states Pienaar, "it’s about making this work appealing to the next generation."

It also means working with nature rather than against it. The baskets allow for better spacing and positioning, which improves water circulation and access to phytoplankton. This not only supports healthier growth but also helps with consistency and managing mortality rates.

"We see less disease and better growth at lower densities," says Pienaar, "and the gear helps you maintain those ideal conditions."

While the upfront cost is higher than traditional mesh bags, according to Pienaar, many farmers see a full return in less than three years – particularly once they scale up operations and begin selling more uniform oysters.

"Yes, it’s a bigger initial investment," she notes, "but you get that back quickly with lower labour costs and higher prices for better quality oysters"

© Seapa

Global reach

Almost three decades on, Seapa supports oyster farms in over 30 countries – from Australia to Japan, France to Canada – each with its own environmental, regulatory and cultural complexities.

“Selling in France is nothing like selling in Korea or Japan,” Pienaar remarks. “The culture is completely different – so is the way they farm.”

In France, centuries-old practices and slow regulatory shifts mean adoption takes time. “You can’t just show up with a new tool,” she explains carefully. “You need to show you understand their way of working. You need boots in the mud.”

That commitment to local understanding has led to long-term relationships – like the one Seapa has built in Normandy. “We first introduced our baskets there 15 years ago, but storms made the clips wear quicker,” Pienaar recalls. “We stayed in touch and eventually co-developed a new clip and clamp bearing that could withstand the conditions. Now that farmer uses Seapa baskets adapted to his trestle system.”

Elsewhere, change often moves faster. In the US, younger farmers tend to be more open to innovation – especially when the return on investment (ROI) is clear. “They’re looking for ways to grow faster,” Pienaar observes.

Japan, meanwhile, has undergone a dramatic shift. Traditionally, the industry relied heavily on wild-caught oysters, but after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami devastated coastal areas, many producers were forced to rethink their entire approach.

“There was growing pressure to produce consistent, premium oysters – not just a bulk commodity.” Pienaar explains.

While natural spat still remains the largest section of the market, this prompted a broader transition toward hatchery-based, single-seed farming, which allows for greater control over quality, uniformity and yield.

© Seapa

Revo and the offshore frontier

As prime coastal zones become saturated or environmentally constrained, oyster farming is pushing offshore. SEAPA anticipated this shift with the development of the Revo range – gear specifically engineered for deeper water to finish off oysters.

With reinforced hinge points, adjustable buoyancy, and compatibility with mechanical flipping systems, After extensive field trials in Australia, the gear is now being tested in France, Japan and beyond.

“For instance, we just recently deployed our first 400 Revos in Texas with the Oyster Bros,” notes Pienaar. “First surface drying systems in the state!”

“In Australia, most intertidal leases are already used,” she adds. “If you want to expand or acquire new leases, offshore is the next step. We see the same trend in Japan and parts of the US”

France, by contrast, remains largely intertidal due to environmental and regulatory constraints. However, Seapa is seeing a slow evolution in growing systems, with younger farmers trialling innovations like adjustable longlines and adapting gear to fit existing trestle infrastructure.

“Each market is different,” says Pienaar. “What works in Alaska – submerged systems under ice – isn’t what works in the Gulf of Mexico or on the East Coast. In the end there is no 'one size fits all', your gear needs to work for you and based on the site and the seed you have.”