After a 40-cage Nile tilapia farm opened on Ghana’s Lake Bosomtwe in 2012, environmentalists immediately raised concerns over potential non-native fish escapes into the lake. The farm also drew criticism for opening without prior approval from Ghana’s Water Resources Commission and Environmental Protection Agency. Though the farm ceased operating in 2015, local fishermen have reported catching non-native Nile tilapia along with native fish species.

© Efua Konyim Okai

To verify the fishermen’s claims, researchers sampled over 1,500 fish from the lake – hoping to estimate the relative density of Lake Bosomtwe’s Nile tilapia population. The case study, which was published in BioInvasions Records, shows that the introduced Nile tilapia are rapidly colonising the lake’s habitats and competing with native cichlid species for resources.

The study and results

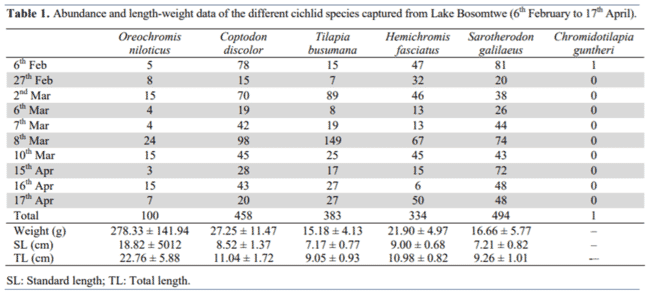

The researchers wanted to estimate the presence and abundance of the various fish species in Lake Bosomtwe, taking 10 samples from the lake between February and April 2020. They dragged a 100m x 6m seine net through the lake and counted and categorised the fish they captured. They used FishBase as a reference for their classifications.

Of the 1,770 individual fish sampled, 100 were Nile tilapia. Based on these results, they estimated that Nile tilapia constitute between 2 and 10 percent of the captured cichlid species in the lake. They also noted that adults of native cichlid species tended to be significantly smaller than the introduced Nile tilapia.

Why it matters

The researchers note that Bosomtwe’s native cichlid species have lower fecundity rates and are already vulnerable to fishing pressure – any habitat or resource competition from Nile tilapia could threaten the species’ long-term outlook. Since Nile tilapia are able to “colonise” new ecosystems by carrying fertilised eggs to new locations, the invasive tilapia population will likely spread. The fact that Lake Bosomtwe is only 8km wide further enhances these risks.

Though aquaculture operations can mitigate the risk of fish escapes by adopting strict biosecurity measures and investing in closed-containment systems, this isn’t always economically feasible. When fish are raised in floating cages escapes are inevitable.

In this case, the factors that contribute to Nile tilapia’s success as a farmed product are the very reason it poses a risk in non-native environments. The study’s authors stress that Ghana’s poorly defined conservation goals and lax biosecurity measures at fish farms are threatening the country’s aquatic biodiversity. As there have been other reports of fish escapes in Ghana’s Lake Volta region, the problem will likely persist in the future.