While fairly good, data-based advice does exist for the most popular seafood choices, the same often cannot be said about less familiar species increasingly promoted as “abundant and underutilized.”

Americans should eat more fish for both their own health and the health of the environment, but ardently building demand for some lesser-known species can have the opposite effect when data are lacking or ignored.

The focus on so-called “trash fish,” bycatch and species that do not earn enough at the dock to warrant harvest, is often promoted as the intersection of the three pillars of sustainability—people, planet and profit. When plentiful fishes seldom harvested come into vogue, some argue pressure can be alleviated on overfished stocks, while embattled commercial fishers can land what the ocean is providing rather than what consumers are demanding.

To many sustainably-minded seafood consumers it’s a no brainer that dovetails with the popular local food movement. Eating less familiar species that are seasonally abundant in local waters is akin to eating what nearby farmers produce and sell at the local farmer’s market. Many assume that along with environmental and economic advantages that may come with consuming what is locally abundant, there are also health benefits. While this may sometimes be true, it is not always the case.

Eating more seafood is good for one’s health, and having locally abundant options can make consumers feel better about eating more seafood. It’s critical, however, to also acknowledge the complexity of offering consumption advice.

Creating demand and building markets for “trash fish” is an uphill battle, but it’s one in which many national media outlets, NGOs, advocacy groups, politicians, and fishing industry advocates have engaged. Unfortunately, they have not always done so in the most responsible, data-centered manner.

Promoting the Least Popular Seafood for Dinner

“In a time when the demand for fresh, local food grows steadily, it’s a wonder that most people still eat the same grocery-store fish staples—salmon, tilapia, flounder, tuna—regardless of where they were caught,” wrote chef Joseph Realmuto earlier this month in a New York Times Style Magazine article titled “Montauk’s Least Popular Fish—for Dinner.”

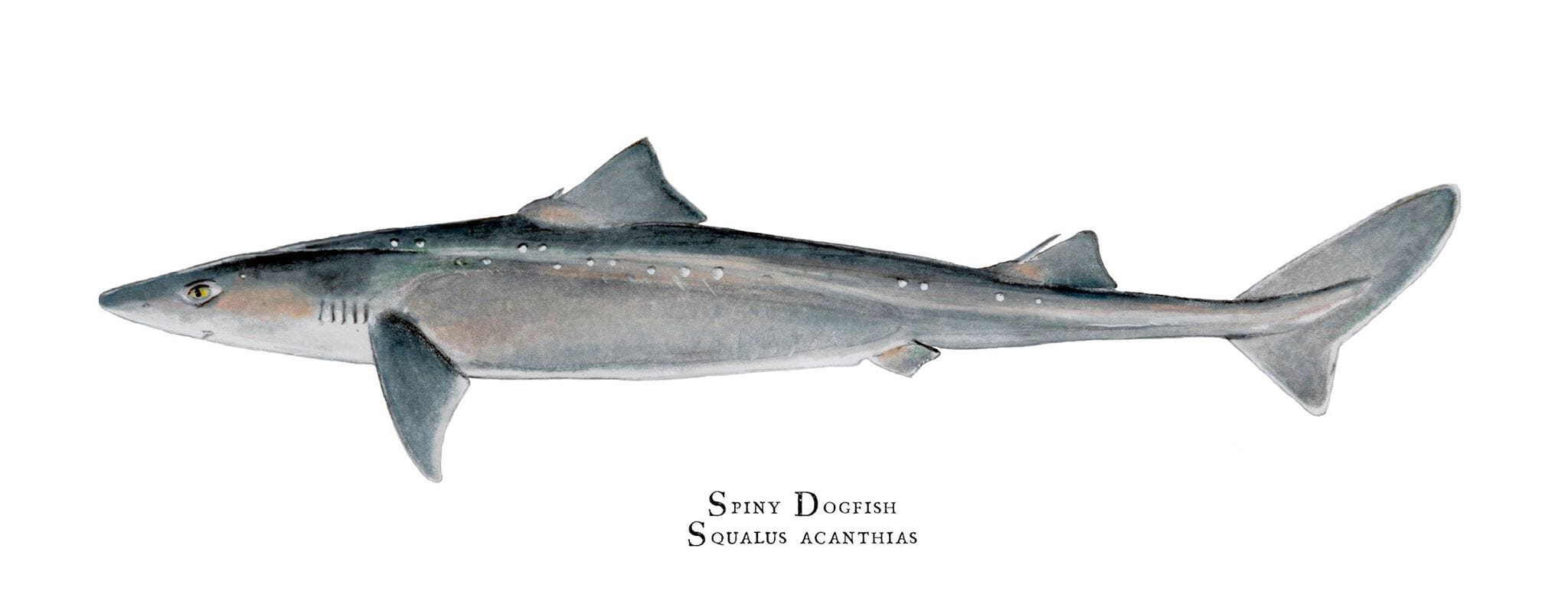

Realmuto’s advice? Try smooth dogfish (pan-roasted with white wine and garden vegetables). The following week, in a blog post titled “Out of the Blue: Diversify Your P(a)late,” the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) promoted the Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s (GMRI) ongoing initiative to raise consumer demand for the closely related spiny dogfish.

“Responsible consumption of underutilized species like dogfish supports the regional fishing industry while maintaining a healthy Gulf of Maine ecosystem,” states GMRI in its literature, recommending roasted dogfish with red curry and bok choy.

Then in late July, Cooking Light magazine, the nation’s leading cooking magazine and a self-proclaimed authority on nutrition and health, named spiny dogfish as one of 12 fish species “you should eat now” (grilled on late summer caponata).

Referring to the article, which is titled “Eat More Fish. The Right Fish. Here’s How.”, editor Hunter Lewis writes, “I hope it inspires and empowers you to try new fish—for your own health and for the health of the oceans.”

What the Data Show

So is eating dogfish good for both your own health and for the health of the oceans? Because there has never been serious domestic demand for dogfish, there is not a lot of published species-specific health and nutrition data.

Still, dogfish is a shark, and sharks are generally known to have elevated concentrations of mercury that pose a risk to human health, especially in at-risk populations.

The Food and Drug Administration and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) advise women of reproductive age and young children to avoid shark altogether, and the published peer-reviewed data show that both spiny dogfish and smooth dogfish exceed the EPA’s threshold for mercury in seafood.*

Some would argue that is a critical piece of information for consumers to know when being advised to eat dogfish, yet the New York Times, CLF, GMRI, and Cooking Light all fail to mention it.

When we begin to pivot toward underutilized species, we need to remember that these species’ health and nutritional profiles may be data-poor. Take, for example, the fact that there are more than 2000 individual samples of cod cited in the most comprehensive published database regarding mercury in seafood.

Now consider that there are fewer than 300 samples of dogfish, and even fewer when it comes to other underutilized species like wahoo and monchong, both of which are promoted in the Cooking Light article and both of which exceed the EPA threshold according to the available data.

While one-third of the species recommended in the Cooking Light piece have mercury concentrations high enough for both state and federal agencies to advise at-risk populations to avoid them, there is not a single mention of any health risks in the article.

.jpg)

In addition to the human health considerations, creating markets for underutilized species in the absence of sufficient data or fishery management can lead to over-exploitation.

One need not look very far back in landings data to identify boom-bust cycles clearly showing that when demand increases, an underutilized species may not remain underutilized for long. This is how “cussed dogfish,” best known for fouling fishing gear in the early twentieth century, became overfished when European markets soared in the late 1980s.

It’s how New England sea urchins went from being considered a pest infamous for clogging lobster traps and clear-cutting kelp beds to fishery collapse when Japanese demand skyrocketed. The story of the oyster toadfish in New York waters is a more recent cautionary tale linked to domestic markets. Hopefully fisheries managers have learned their lesson—data-based adaptive fishery management needs to be in place before a market for a so-called underutilized species is developed.

This is especially the case when dealing with a vulnerable species like the spiny dogfish, which is relatively slow-growing and has the longest known gestation period of any shark species.

Eat More of the Right Kind of Seafood

In our collective enthusiasm to promote sustainability, support local fishers and eat more healthily, we must not ignore the complexity associated with issuing responsible advice. Just because a fishery is certified sustainable doesn’t mean the seafood harvested in that fishery is a de facto healthy choice. Just because a fish is local, doesn’t mean that the health risks associated with consuming it are automatically less.

Just because a species is touted as “abundant and underutilized,” “underloved” or a “trash fish,” doesn’t mean that every consumer should be advised to eat it.

Eating more fish is crucial to our health, the health of the Earth and to the future of global food security, but we must not focus myopically on just sustainability or just health when issuing advice.

Many species of seafood are low in mercury, high in Omega-3s and sustainably harvested or farmed.

For a variety of reasons ranging from overfishing to global climate change, we are going to be eating more unfamiliar species, but before jumping headlong into a marketing campaign for abundant and underutilized species, we must be sure we have the data that will allow us to both manage the fishery and make informed decisions about our own consumption and how it may affect our health.

In short, we must eat more of the right kind of seafood.

August 2015

*The EPA’s threshold of 3.0 ppm for mercury in seafood is based on the reference dose—a maximum acceptable daily oral dose of a toxic substance such as mercury. Unlike the FDA threshold of 1.0 ppm, which is intended more as a regulatory “eat-don’t-eat” action level, the EPA threshold allows for quantifying different levels of risk.