Wallace sees aquaculture as helping to bolster the islands' economy and a way to responsibly make the most of their natural resources. © James Wallace

According to its supporters, the planned £350 million project would help to revitalise the archipelago’s struggling economy and create new employment opportunities in a community that’s over reliant on governmental jobs. However, recent history shows that there’s also vocal and effective opposition to aquaculture within the islands' 3,000-person population, leaving the fate of the project hanging in the balance.

The initiative is a joint venture between Falklands fishing firm Fortuna and Danish aquaculture consultancy company F-Land ApS. And representatives of these companies James Wallace – an eighth generation Falkland Islander – and Morten Bjørn, who brings 20 years of aquaculture experience to the table, explained to The Fish Site their ambitions for the project and the obstacles it needs to overcome.

The seed is planted

According to Bjørn, who has worked for companies including Akva, Pentair and Pisco, the idea to start salmon farming in the South Atlantic came to him at an aquaculture conference in Norway 2016, when he saw a presentation that covered the zones of the world that were suitable for salmon farming. All but one had farms already established – and that spot was the Falklands.

Further research revealed that the archipelago had in fact been home to a small salmon farming business from 1987 to 1990. Despite challenges based on logistics, input supplies and inexperienced personnel, the project showed that, from an operational standpoint, salmon farming is indeed possible in the Falklands, with suitable temperatures and sea states – although it was eventually killed off by the crash in salmon prices that took place at the time.

It was also a time, as Bjørn observes, that there was still huge scope for industry growth in the established regions, such as Norway, Scotland and Chile, which were hard for the isolated farmers to compete with. However, these days, opportunities for establishing traditional net pen farming operations in pristine coastal locations are as rare as hens’ teeth. As a result, Bjørn decided to investigate further and soon established contact with Wallace, whose company owns the largest fisheries quota in the islands, who was quick to grasp the opportunity.

“From Fortuna’s side, we are not aquaculturists, but we’ve been encouraged by years of government support for diversification — aquaculture fits that brief, and as the leading company in the Falklands, we’ve always believed it is our job to actively pursue serious opportunities. So when we were approached by Morton and his colleague, we thought that we should do the responsible thing and to look into it properly,” Wallace recalls.

The sites will be supplied with smolt from hatcheries in Mare Harbour and Newhaven

Local opposition and a shock result

Wallace and Bjørn duly looked into - and found - plenty of suitable locations for both land-based smolt facilities and net pen grow-out sites. However, following the initial announcement of their plans, Wallace was surprised to encounter vocal opposition and shocked by how effective this opposition proved to be – particularly given the long-term governmental encouragement of aquaculture.

“Aquaculture was a key part of the Island Plan, which is our government's top level strategy document, for many, many years. And just after we teamed up with Morton and his colleague and pulled together this proposal we were in talks with the government, and were arranging fact-finding visits and other exercises to help the government inform themselves. But the process was hijacked essentially by a small group of local activists, which led to the government banning aquaculture in March 2022,” he explains.

Unity Marine decided to mount a legal challenge, as they felt that the project had not been given a fair hearing.

“The concern was that they [the government] just tried to essentially overlay what has happened in the Chilean aquaculture sector into the Falkland Islands without actually carrying out any foundational research,” Wallace points out.

The court agreed and the government have now been tasked with reevaluating their decision.

“They were ordered to make a fresh decision, was based on evidence, not on fear-driven opposition. So we're in the middle of that consultation process now and the government will be taking a fresh decision towards the end of the year. So we've got a bit of a battle on our hands,” Wallace explains.

© Unity Marine

What’s at stake?

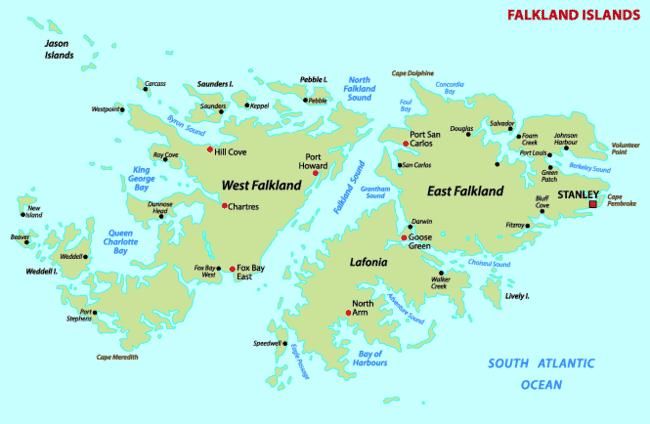

Unity Marine’s proposal includes two hatcheries on East Falkland, which would produce smolt for 16 sea sites – roughly divided between the island’s east and west coasts.

While the planned production capacity is 50,000 tonnes – which is essentially critical mass for a farming company operating in such an isolated location, according to Bjørn’s calculations – he notes that carrying capacity studies suggest the potential for the area to produce up to 130,000 tonnes a year.

The sea sites are likely to be equipped with technology similar to that used by Huon in Tasmania, with tall predator nets to keep out seals and sea lions, and bird nets with escape hatches.

Third party processing vessels – akin to the Norwegian Gannet – will be used to process the fish, before transporting them to Chile for distribution and Bjørn says that he's been in contact with several interested players to fulfil that role.

However, he stresses that the company would need its own wellboat, as it would not want to compromise the biosecurity of a pristine site with vessels that had been handling live – potentially pathogen-carrying – fish in Chile. Meanwhile a small processing facility on the islands is planned to serve the local population, the military, and cruise ships.

The project is expected to create 160-170 full-time roles, and Bjørn expects about a quarter to be filled by locals, a quarter by expats, and half by rotational shift workers from Chile – a model that largely mirrors the local fishery sector.

“There's basically no unemployment on the islands, but what we do think is that it will give opportunity to young Falkland islanders in the future to actually have a broader range of jobs available for them when they return from their studies in the UK,” Wallace explains.

He’s hoping that such positives will be evident to the island’s authorities after seeing for themselves the opportunities that salmon aquaculture – done well – has generated in other areas.

“We're organising a fact-finding mission to visit a salmon facility in Norway, which will be happening in May. We're going to be taking some local stakeholders, including government officers and hopefully some local politicians to see how to see what a well-run salmon facility looks like. Which is important because the closest reference of course is Chile, which is not the reference we should be using,” Wallace points out.

© Morten Bjørn

Next steps?

The trip to Norway is likely to be critical to the outcome of the project, as the final decision on whether to allow salmon aquaculture to return to the archipelago will be made by three members of the Falklands Executive Council, based on information gathered by government officers.

Should it be green-lit then the initial step is a £4 million environmental impact assessment (EIA).

“I think that's the only responsible way to actually determine whether or not the environmental risks can be managed,” notes Wallace.

“From the beginning, we've looked at as many things possible to make it the highest standard in the world. So we've looked at how to minimise or mitigate a lot of those environmental challenges. We advocated that we had to do it right from the beginning and not do the mistakes that have been done in other jurisdictions with an organic growing industry on the basis of no legislation,” adds Bjørn.

If the EIA goes well, then investors capable of providing the £350 million needed to reach the 50,000 tonne mark will be sought out in earnest.

“There is interest in the market for projects like that. It most likely will be a combination of investments but also there'll probably be loan guarantees from government like export credit financing from the Norwegian or potentially the Danish government,” explains Bjørn.

They will also consider investments from established salmon companies and, if approved, the first salmon produced in the Falklands since 1990 is expected to be available by the end of the decade, potentially paving the way in the longer term for the Falklands to grow into a major new source of salmon.