The use of probiotics may now be considered as commonplace by most of the world’s shrimp farmers, but if it hadn’t been for the tireless efforts of an Australian with a bright idea and an appetite to defy conventional wisdom, the shrimp farming industry might be considerably less sustainable than it is today.

The man who has since been dubbed “the grandfather of shrimp probiotics” is Professor David Moriarty – a pioneering researcher who was happy to eschew 5-star hotels in favour of pond-side accommodation to ensure that trials on his new health products were carried out to his own exacting standards. After facing disbelief, and even scorn, from many of his fellow academics, David was on a mission. A mission that was to change the face of shrimp farming in Southeast Asia and beyond.

Water quality and the development of a novel idea

David cut his teeth as a microbiology and ecology researcher – following his doctoral studies on the oxidation of sulphides by thiobacilli. In 1969 he was appointed as biochemist/microbiologist to a Royal Society International Biological Programme project on the tilapia-rich Lake George, in Uganda. By the 1990s, after undertaking a variety of projects in Australia, Malaysia, China and India, he was keen to use his extensive experience in the field to look into developing products that could help to improve water quality, and thus animal health, in pond-based aquaculture. It was a decision from which the entire shrimp sector was set to benefit.

David took up a position as a research scientist in a marine division of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation of Australia (CSIRO) in 1975. A major achievement of his time there was the quantification of bacterial growth rates in the water and sediments by determining rates of DNA synthesis in situ.

Fish and shrimp (prawn) aquaculture are major industries around the world, but in many regions are severely limited by disease. It became clear to him in the 1980s that the best way to control disease in aquaculture was by managing microbial processes in the pond and fish tank environments and to use appropriate natural bacteria to assist in those processes.

“Antibiotic abuse was rampant in the Americas and Asia, with large quantities of ‘last-ditch’ antibiotics for treatment of humans being added to ponds in large quantities. That actually made the disease situation worse, as many antibiotic resistance genes are linked with those for pathogenicity. Furthermore, shrimp infected with pathogenic bacteria are more prone to viral disease. The impact of antibiotic abuse, which is a major issue for human health, is now being recognised. For example, McDonald's announced that they will sell chicken meat only from farms that do not use antibiotics for growth promotion,” he explains.

As a result David decided to tackle the issue head-on, initially seeking some research funding.

“I wrote a proposal to CSIRO’s chief executive outlining how research into factors leading to disease and mortality in aquaculture ponds would be worthwhile. But, the government had cut funds to CSIRO so I had to look elsewhere,” David recalls.

So David decided to go it alone – albeit with a little help from his family.

“Leaving CSIRO was a significant risk, but my wife Chris supported me, and our eldest daughter, who had just finished her BSc, assisted with the research for developing the probiotics,” he says.

He set up a small private company— Biomanagement Systems — with Adam Body in Darwin, Northern Territory, where he developed probiotics and procedures to control water quality and pathogens by changing bacterial species composition in ponds and hatcheries and in the alimentary tracts of fish and shrimp, without the use of antibiotics. This was achieved by selecting appropriate, safe strains of Bacillus species that occur naturally in aquatic systems and producing them in large enough numbers at a cost-effective price for commercial application.

“There were other companies producing and selling various bacterial products, but they were mostly ineffective as they were not based on sound knowledge of microbial ecology. This caused shrimp and fish farmers to question the concept of probiotics,” he explains.

In order to counter the latent scepticism of the industry David then had to demonstrate that his products worked in the field.

“The next step was to test our new strains on commercial shrimp farms. Field trials and proof of performance were done in Indonesia in 1995-1996 and then in India, Thailand and Philippines,” David adds.

The results – gained through David’s extensive, meticulous field trials – were promising. But his next challenge was to commercialise his products, which were among the first probiotics in the world to be developed for the shrimp sector.

“The Bacillus probiotics were selected to compete with and displace pathogenic vibrios. Not only were they a replacement for the antibiotics that were rife in the shrimp sector back then, they also worked with other specially selected Bacillus species to improve pond water and soil quality by degrading wastes. That lessened the environmental impact of the farms’ effluent water. The probiotic Bacillus also improve the gut flora of the shrimp, thus lowering disease incidence and increasing food assimilation,” David explains.

Teaming up with INVE

David’s initial claims of success were met with scepticism by the academic establishment, but Patrick Sorgeloos, from the University of Ghent, was intrigued by David’s results and invited him to speak at a seminar in Ghent in 2003. There he met Olivier Decamp – now in charge of INVE’s probiotics programme – who had recently joined the Belgian firm from The Oceanic Institute, Hawaii.

“I still had an academic mindset and had doubts about the efficacy of the formulation, and more specifically the benefits associated with a relatively small number of Bacillus cells. All of us at INVE’s research & development department came from academia, and were used to trials under controlled conditions and were unsure of the results from farm trials,” Olivier reflects.

However, Olivier – like others at INVE – also saw that David’s belief in the project was genuine and was aware that his goal – finding an alternative to antibiotics – was essential if the global shrimp industry was to develop on a sustainable basis.

“There was no doubting that David believed in his results: he took a huge risk, going from a steady civil servant’s job to embark on something he believed in – an alternative to antibiotics. It was his crusade,” Olivier recalls.

As a result, INVE’s management decided to go for it and David was receptive to the idea of cooperating with the Belgian firm.

“INVE approached me about collaborating and I was impressed by their reputation for integrity, their large network for marketing aquaculture health products and their excellent facilities for developing new products and bacterial strains,” David says.

And, in 2003, they embarked on what was to become an extremely fruitful partnership.

“We started with research at Ghent University and INVE’s research centres to select and test numerous Bacillus strains, for activity against pathogenic vibrios. Other properties that were sought in the Bacillus species included a wide range of exoenzyme secretion to assist in degrading wastes, and the ability to grow under a wide range of conditions (salinity, temperature and aerobic/anaerobic). At the same time I worked with INVE teams in Belgium and Asia to develop manufacturing processes to produce the very large quantities of Bacillus that were required for worldwide marketing, especially for use in the very large ponds in the Americas,” David explains.

Meanwhile, they were also working to evaluate the new products in the research centres in Thailand and Ecuador, and then in the field – trials which vindicated INVE’s decision to work with David.

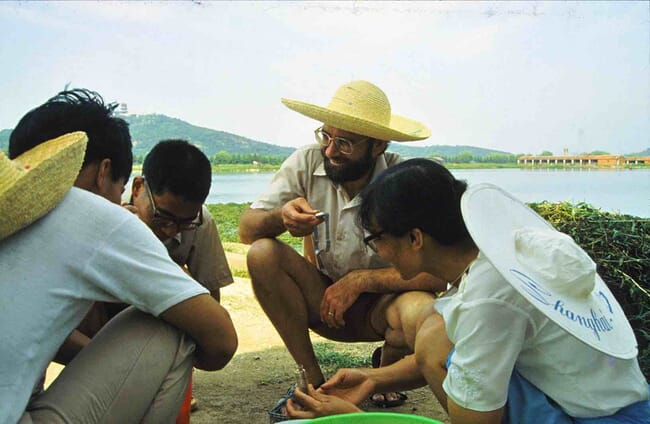

“We gave David four months in India working with Mr S Chandrasekar [recent president of the Society of Aquaculture Professionals in India and INVE’s Area Manager for India] and Mr Nagarajan [INVE’s sales manager], who had been given the use of a large number of ponds by a major Indian corporation in which to trial his probiotics. David worked and slept pond-side. The results were very positive. Working alone he’d achieved more than a whole generation of academics,” Olivier says.

Converting the sceptics

The success of the products in India and other locations justified INVE’s faith in David, but they still had to convince an industry injured in the use of antibiotics that there was a more sustainable alternative on the market. And, as a number of papers published at the time reveal, even many academics remained unsure of David’s claims.

As a result, David and INVE embarked on a series of workshops for the distributors of the probiotics; wrote numerous academic papers on the trials; spoke at conferences around the world, including Fenacam in Brazil, AquaExpo in Ecuador, and the Society of Aquaculture Professionals in India; and visited numerous farms to explain the technology and provide advice on pond and hatchery management.

“Farmers were much more accepting of the concept once they saw how well the products worked and much of David’s advice is now being adopted by the large corporates,” says Olivier.

“However, we first had to try to convince farmers that probiotics were not an ‘instant cure’ medicine, but a way to assist the management of the whole microbial community in ponds and the intestinal tracts of shrimp and fish. The most important management concept that many farmers did not understand was that bacteria played key roles in mediating the relationship between stocking density, daily feeding rates and dissolved oxygen concentration, and their impact on survival and shrimp growth rates,” David explains.

The results

INVE and David have since gone on to develop a whole range of probiotic products including the water treatment product (Sanolife PRO-W), shrimp hatchery (Sanolife MIC) and feed probiotics for shrimp (Sanolife PRO-2 and PRO-S FMC).

“INVE has good teams of technical staff for both production – where quality control and checking product safety are very important – and for marketing: providing advice to customers on how to apply the microbial biotechnology to pond and hatchery production,” David explains.

“We were able to develop products with mixtures of different Bacillus strains that were packaged together and which had a long shelf life. The advantage of Bacillus is that they produce heat-resistant spores, so could be spray-dried and then different species combined into the products for various end uses,” he adds.

The end result has been a huge improvement in the sustainability of the global shrimp sector as a whole – an achievement that David is justifiably proud of – although he’s also quick to thank those farmers who were among the first to adopt his products and techniques.

As David explains: “Until recently, it was hard to convince farm managers and owners that antibiotic use actually made disease worse for them, but our results showed otherwise. Even as far back as 2001 Alex de Wind at Bravito in Ecuador listened to my explanations and changed his hatchery and pond management using the probiotics I’d developed. He achieved high survival rates, excellent feed conversion ratios and improved water quality.

“Similarly in India, Indonesia and the Philippines, good results were obtained on farms where my technology was applied, even before I started working with INVE and was able to develop better quality products.”

“The Hi-Line Aqua group, led by the late Dr Vasudevan, were very supportive in promoting the benefits of my technology in the late 1990s and continued to do so after I started working with INVE. They introduced me as ‘the grandfather’ of probiotics at meetings of shrimp farmers!” he chuckles.

The collaboration, while requiring a lot of time and effort has also worked out well for INVE.

“It hasn’t been easy – we weren’t making any money from probiotics to begin with either – but it’s been worth it. We facilitated his research and encouraged his concept to grow, with a supportive team offering marketing insights and quality control skills, as well as plenty of encouragement – we believed in the idea and were willing to invest in it,” says Olivier.

“And the end result is that David has been involved in the development of numerous products for shrimp and fish, in hatchery, nursery and grow-out, and the uptake has been considerable, especially in Asia, Latin America and – more recently – Europe and Africa,” Oliver continues.

The future

Having achieved a huge amount in aquaculture, after a decade working as a consultant for INVE, David retired in 2013, becoming an Honorary Senior Fellow at the University of Queensland’s School of Mathematics and Physics, where he is engaging in research on eclipsing binary stars.

“I’ve had a lifelong interest in astronomy and, being a scientist, I wanted to contribute to research, not just look at stars,” he reflects.

In the meantime, INVE is continuing David’s crusade and is continuing to develop and improve their range of probiotics – most recently, the improved Sanolife PRO-2, which was developed with shrimp farmers in Southeast Asia and South America – as part of their care for growth concept, much to David’s delight on a recent trip to Thailand.

“Coming back to Thailand five years after retiring as a microbial ecologist, it’s been a pleasure seeing how the application of the microbial technology has expanded under Olivier’s guidance. His enthusiasm, and that of the large team now working with him on probiotics, indeed shows that the future for INVE – with high quality products and sound, scientifically-based advice to the aquaculture industry – is in good hands,” David concludes.

Indeed, as well as Olivier, David’s mission is now being continued by a whole new generation of INVE probiotics experts – including Peter De Schrijver, who is developing new formulae at the company’s R&D centre in Belgium and Marcos Santos, who has been integral to the uptake of probiotics by aquaculture producers in Brazil.