The EU’s protein deficit has been well documented, and it might seem that over the past few years precious little progress has been made in decreasing Europe’s reliance on imported feed. However, the search for alternative sources of amino acids has been leading original minds down some unlikely avenues – not least in the use of black soldier fly (BSF) as a suitable source of protein in fish feeds, an approach that has been attracting growing interest from across the aquaculture industry.

The larvae of this unassuming insect, Hermetia illucens, has proved to be an ideal candidate for supplying fish feed with homegrown protein. Normally hatching in decaying matter such as compost, the larvae (BSFL) have a voracious appetite and are capable of reducing waste into a viable fertiliser in a very short space of time, making them increasingly popular in home composting systems and therefore in plentiful supply. Yet until very recently, their own potential as a source of protein for the animal feed industry could not be realised in the EU. The classification of insects as a ‘production animal’ and the restriction on the use of such animals in feed remained a barrier to commercialisation.

However, a resolution made by the EU in 2011 to address its protein deficit meant the potential could no longer be ignored. In 2013 an EU-funded three-year project, PROteINSECT, was established to assess the safety of insect proteins for use in animal feed and to develop and disseminate production techniques. The European Food Safety Authority deemed the new ingredient to be safe in 2015. But it was not until December 2016 that EU member states finally voted to allow the use of insects in aquaculture feed.

In theory this has given the green light to commercial insect producers to increase production and capitalise on a rush to balance the EU protein deficit. Unfortunately, despite its wide use in domestic and small-scale composting, producing BSF on a commercial scale has proved difficult.

One company that has managed to navigate this bottleneck is Ireland-based Hexafly.

“The real technical challenge was the breeding, getting them to reproduce on a commercial scale all year round has proven difficult,” explains CEO Alvan Hunt.

Hexafly was founded by Alvan and three other young entrepreneurs who met while at university. They launched the company in response to “a lack of innovation in agri-tech” and it now has a the capacity to produce 47 tonnes of larvae per year at its facility near Kells, in County Meath.

Alvan makes it clear that the company’s ability to produce on such a scale is not down to luck. “Although the company is quite young, our R&D has been going on for quite some time,” he reflects.

The company has inevitably attracted the attention of feed producers and investors. “In May last year we were approached by an American venture capitalist fund and we were enrolled in an accelerator programme. This involved four months of intense training, mentorship and commercial insight. It gave us a great boost and we got to work with some of the global leaders in this field,” says Alvan.

The company has also been accepted to the YieldLab agricultural technology start-up accelerator fund, which has recently established itself in Ireland.

And Hexafly is expanding rapidly on the back of this interest. They have already outgrown the existing facility and plans to establish another are well underway. Alvan hopes to bring Hexafly’s total number of employees up to ten by mid-2018. As the company reaches this scale, it will become less laboratory-based and more of a manufacturing plant – increasing output is a major priority.

“The company needs to go global,” explains Alvan. “The requirements are enormous – even if the larvae can account for two or three percent of fishmeal production it’s a massive opportunity.”

Of course, producing such a large quantity is of no use if fish and feed producers prove sceptical about this new ingredient. Alvan is enthusiastic and optimistic that both industries can see the value.

“The price of farmed fish is still rising and, even if it stabilises in the long term, there is an incentive to increase our production because of stricter fishing quotas. Feed manufacturers can’t immediately offer something new but they can understand from a strategic perspective that, if they don’t have other things in the pipeline, in a couple of years they will be faced with a potential disaster,” he argues.

Alvan also addresses scepticism regarding the quality of BSFL meal as a suitable replacement for fishmeal. “Its amino acid breakdown is very beneficial, it’s got high digestibility and a good breakdown of proteins. It’s a good, stable protein source,” he says.

Feeding trials on a wide range of species have shown that replacing up to 60 percent of fishmeal in commercial diets with BSFL meal can return almost equal results in terms of feed conversion ratio and fish quality. Hexafly are set to start their own feed trials soon.

Alvan is also keen to point out the efficiency of producing BSFL when compared to other sources of protein. “We can produce protein in a small area and, if we compare that to the production of soya beans or to fishmeal, what we’re doing is essentially a 90 percent reduction in greenhouse emissions,” he says. “And we are essentially upcycling waste at the same time.”

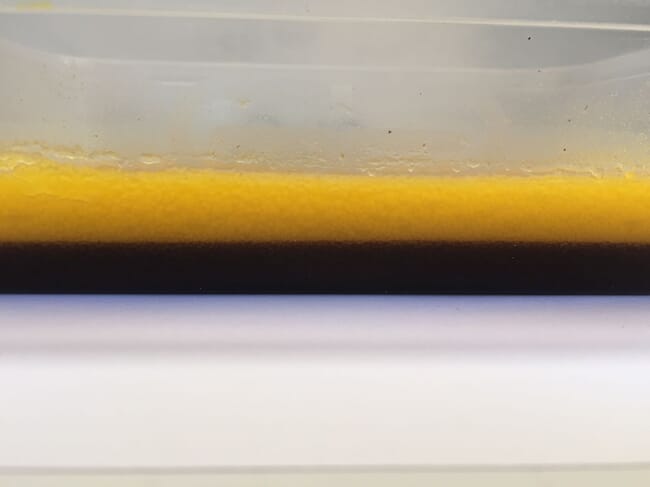

Another advantage to BSFL production is its by-product frass, the larvae’s excrement. It is a fine, odourless powder that can be put to use as an organic fertiliser, giving the whole process further green credentials and opening up another income stream for the producer.

Its environmentally non-invasive nature should also make BSFL an attractive ingredient to the organic salmon industry – which dominates Irish salmon production.

“In the long run we hope to target the organic salmon market,” Alvan says. This requires diets with a high omega-3 content. Obviously fish oil and fishmeal are excellent sources of omega-3s, but we have a programme to boost the omega-3 levels in the substrate [the waste the larvae are raised on] in the future and then we will be able to directly market this to the organic salmon producers.”

The company’s economic potential remains to be seen, but investors seem confident in its success – and Alvan speaks about the entire enterprise with the enthusiasm and energy that only a young entrepreneur can. It’s a passion that’s not only inspired by the potential for financial gains. As Alvan summarises: “If we got this up and running, even to make a small difference would be fantastic. If you look at global food production, we really need to start moving towards something better now. I genuinely think we can have a positive impact on the whole world.”