South Africa’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) recently launched a “Citizen Science Survey for Nile Tilapia”, with the purpose of sourcing knowledge on the distribution of the exotic species in the country’s watercourses.

The deadline for submissions has been extended to 28 February 2018. According to CSIR environmental scientist Lizande Kellerman, the survey forms part of a national Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) to promote sustainable aquaculture development in South Africa. Aquaculture is considered to be one of the fastest growing food production systems in the world and Oreochromis niloticus and its hybrids account for approximately 80 percent of worldwide tilapia production.

Hybridisation concerns

However, the introduction of the potentially invasive O. niloticus into South African river systems, via escapees from aquaculture facilities, is a cause of concern for the conservation of indigenous tilapia, such as Oreochromis mossambicus (Mozambique tilapia, also known as blue kurper in South Africa), which are at risk through hybridisation and competition. In South Africa, aquaculture has contributed to 17 percent of the invasive fish species that have been introduced, but the nutritional needs of local communities mean that the culture of O. niloticus and its hybrids is increasingly being promoted across the continent.

South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT) has placed a moratorium on farming O. niloticus in the provinces inhabited by O. mossambicus – namely the Limpopo, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. Nile tilapia farming is only permitted in six of the nine national provinces. Fish farmers in the other three provinces, which have the ideal climatic conditions to farm tilapia, are appealing to government to allow them to use niloticus.

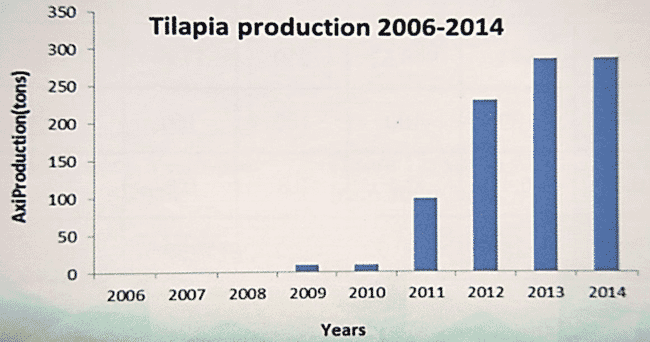

Figure 1 depicts the increase in tilapia production from 2011 to 2014, reaching 300 tonnes per annum. If Nile tilapia were permitted to be farmed in the other three most suitable provinces, production could increase dramatically. Farmers are also frustrated that potential investors are being driven to neighbouring countries with similar climates, such as Zambia, where farming of this species is permitted.

© Sourced from the DAFF Aquaculture yearbook 2015 – South Africa

Zambia has managed to balance the needs of both commercial fish production and conservation. Although the species is present in a number of water bodies, including rivers in Luangwa and Kafue national parks, they have been excluded from Lake Bangwelulu, which is a World Heritage site. The country has a thriving aquaculture industry, with some farms harvesting over 100 tonnes a month. South African fish farmers, meanwhile, are frustrated by being limited to producing O. mossambicus. A commercial strain of Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT) reaches about 500g in eight months, while an indigenous O. mossambicus takes 11 to 14 months to attain the same weight, and has a number of disadvantages including early maturation, precocious reproduction and poor body shape. O. niloticus, on the other hand, has had the benefit of 30 years of selection and improvement on body shape, fillet yield and disease resistance, which has great implications for economic viability. Most African countries have accepted the fact that the benefits of farming with improved strains of Nile tilapia, outweighs its environmental threats.

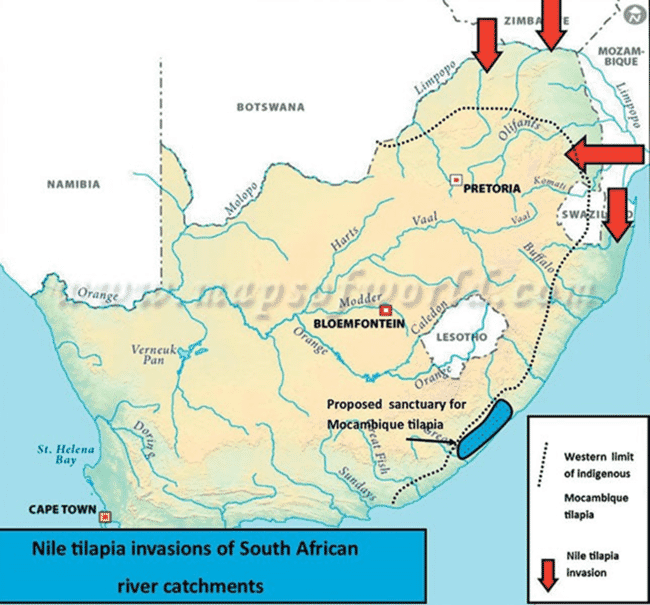

The farmers’ appeals are supported by the argument that Nile tilapia are already in the waterways of the restricted provinces. There are major rivers that cross into South Africa from neighbouring countries, such as Mozambique and Zimbabwe, that have been farming Nile tilapia for decades (Figure 2). Originally stocked in Zambian community fish farms by the Peace Corps, Nile tilapia were translocated to Zimbabwe in the 1990s, spreading to South Africa via the Limpopo River system.

© Nicholas James, 2017

Dr Ben van der Waal, an aquatic scientist, collected samples of O. niloticus, O. mossambicus and O. niloticus and O. mossambicus hybrids in the Limpopo River system in 2000 (see photographs above). The status of the O. niloticus invasion in South Africa has been classified as a Category D2, which denotes an established self-sustaining population, with individuals surviving and reproducing a significant distance from the original point of introduction. O. niloticus requires a permit for purchase, sale, movement and stocking. In South Africa the establishment rate for invasive fish species was 80 percent for inter-basin water transfers, followed by angling (79 percent), biocontrol (75 percent), conservation (73 percent), ornamental purposes (67 percent) and aquaculture (33 percent).

© Stellenbosch University

Characteristics which make O. niloticus a successful invasive species include aggressive spawning behaviour; high levels of parental care including mouthbrooding; the ability to spawn multiple broods during a single season; and a broad diet which includes phytoplankton, zooplankton, detritus, epiphyton, insects and fish. Potential impacts associated with the introduction of O. niloticus may include the following: changes in community structure including decreased abundance and extinction of native species due to habitat and trophic overlaps and competition for spawning sites; introduction of pathogens and parasites; habitat destruction; changes to water quality; hybridisation resulting in loss of genetic integrity and loss of biodiversity. Loss of genetic integrity was shown in a study of individual tilapia identified taxonomically as O. mossambicus, which turned out to carry the mitochondrial DNA of several introduced Oreochromis species, when genetically analysed. Reduced fecundity has also been observed in some hybrids, which may result in reduced fish yields with potential socioeconomic impacts.

© Ben van der Waal

© Dr Ben van der Waal

Nicholas James, a South African ichthyologist and hatchery owner, proposes that sanctuaries should be established which could protect the indigenous O. mossambicus populations from the spread of Nile tilapia (see proposed area in Figure 1). O. mossambicus is the most tolerant of a range of salinities of all tilapia species; it tolerates brackish or even hyper-saline water in estuaries, where it can survive lower temperatures than in freshwater. The Nile tilapia does not thrive at high salinities (above 20ppt) and low temperatures (below 12°C), so these areas exclude invasion and therefore offer a safe refuge for O. mossambicus. While Mozambique tilapia may survive temperatures as low as 9°C, research shows that the improved strains of Nile tilapia cannot tolerate temperatures below 12°C.

In the restricted provinces, the high-lying areas are too cold for Mozambique tilapia, but O. niloticus could be farmed in greenhouse tunnels. Fish grown in biosecure recirculating aquaculture systems (RASs) are of little risk to the environment if correct control measures are implemented. These systems are designed to ensure that no effluent water can ever reach nearby rivers. Such systems would have to be legally situated away from natural watercourses, and all movement of live fish into or out of such systems restricted to permit holders. If these protocols are followed, the use of the species could stimulate a growing and highly desirable freshwater aquaculture industry in South Africa.