In a recent article my colleague, Tanja Hoel, discussed some of the key investment considerations in land-based salmon farming. As detailed by Tanja, there are still a number of technical and operational challenges in this sector. Companies – both solution providers and operators – inevitably create new intellectual property (IP) as they find novel solutions to these challenges. This enables them to offer better, cheaper, quicker products or services than those offered by competitors – whether they be RAS engineering designs for greater biomass production, real-time monitoring of water quality, or new diagnostics for the rapid detection of pathogens. Ultimately, it is this IP which delivers long-term value to the company, its shareholders and its investors.

Freedom-to-operate

While IP can provide competitive advantage for a company, there is a flip side – a competitor’s IP can act as an obstacle to the delivery of products and services to your customers. This can sometimes just be the ability of competitors to offer a better product than yours, but in the case of a patent, this can materialise as an absolute block to offer any alternative product in that area. This is why it is vital that companies ensure they have freedom-to-operate (FTO) for products or services they are developing. FTO offers the reassurance that someone else’s IP isn’t going to block you from providing your products or services.

To patent or not to patent? That is the question

So, in developing new solutions to improve the efficiency, cost base or operation of land-based salmon farming, companies have been creating IP. The question comes down to “how do you most effectively protect that IP?” Although there are a number of mechanisms available to the IP inventor, the most commonly used in aquaculture are either trade secrets or patents.

In many ways these are the inverse of each other. Trade secrets (confidential information which has commercial value and the owner has taken reasonable steps to protect) are based on keeping information secret and are not exclusive. Meanwhile patents are based on full-disclosure, but in return give the inventor 20 years of exclusivity. The decision on whether to keep IP as a trade secret or file a patent is multi-factorial, but is often driven by the nature of competition and revenue model in a particular sector. For example, it is almost a necessity to file a robust patent if developing a new salmon therapeutic, while most salmon breeding programmes are predominantly protected through trade secrets.

What about patents in land-based salmon farming?

Over the last 20 years there have been over 40,000 patents published referring to salmon, while nearly 5,000 of these refer to salmon disease, how many reference land-based salmon farming? Just 370 patent applications grouped in ~70 patent families.

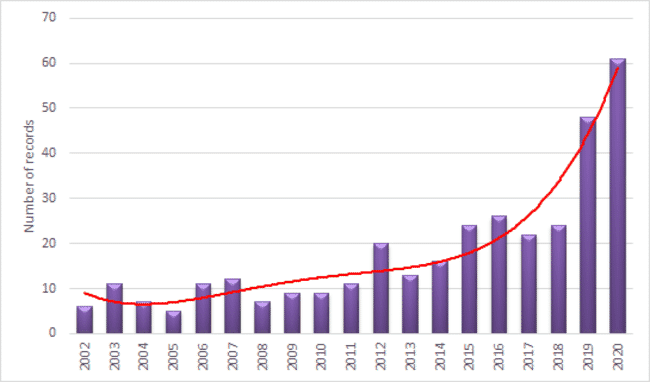

Of these ~30 percent have been granted, while the rest are still being examined. Clearly this is not a large number of patents in such an active market. However, the level of patent activity is on a steep growth phase (Figure 1). For the first 10 years of the 2000s we were seeing around 10 patents published per year, in 2018-2020 this reached 50-60 patents published annually.

It should also be noted that the patenting process, which must be one of the most idiosyncratic systems that humans have ever created, creates a large blind spot, as new patents are only published 18 months after they were originally filed. This means patenting trends are both a lagging indicator (they tell us what companies were doing 1 ½ years ago) but they are also a lead indicator (they can help predict what products or services a company may be launching in the future). So, if the trend in patent activity that was visible 18 months ago continues, when we look back in a couple of years we would expect the level of patent activity in land-based farming at this current moment to be far greater than the statistics suggest.

What has stimulated the growth in patenting?

We often see this trend – a low level of patent activity for several years, followed by a steep increase in activity – in a developing industry. While early players are creating IP through their endeavours they tend to keep these as trade secrets; “why tell the world what you are doing and let them copy your ideas?”. There is also a lot of experimentation and trial-and-error at this early stage so inventors may ask; “why incur the cost of patenting something which may be obsolete tomorrow?”. Finally, as the market is immature and still growing, often the cost of securing a patent (typically €350,000 over the patent’s lifetime) just can’t be justified when compared to the profit that the patented product or service may deliver.

However, as the market matures, the opportunities grow and the competition becomes more fierce, so the balance of that equation starts shifting to “I need to patent my technology if I am going to be competitive in this market”. The other issue as markets and opportunities grow is ‘leakage of IP’. It is one thing to keep your IP secret when it's in your own facility under your own control, it's totally different when you start selling products and services across diverse markets to different companies. Once you know that your IP is going to be distributed widely and out of your direct control then patenting may be the only way to maintain and enforce your rights.

Who? What? Where?

So, who is most active in filing patents in land-based farming? The main protagonists are (not surprisingly) academic institutes across the globe and aqua engineering and technology companies – the likes of AKVA, InnovaSea, Veolia, SeaRAS, Preline FishFarming Systems and Aquamaof. But we also see several of the leading land-based salmon farmers active in this area – notably Atlantic Sapphire, Nordic AquaFarms and Andfjord Salmon.

It’s interesting to look at where these patents are first filed (often an indication of where the IP was created) and where patents are subsequently filed (an indication of where the market opportunity for that invention). In terms of IP creation, the leaders are definitely Norway, followed by the US. In the chasing pack – but quite a way back – are the UK, Denmark and Japan.

However, in terms of where the IP is applied – ie where companies see the opportunity to employ the invention – we see a very different picture: the US is way out of front, followed by a wider spread of countries across Europe, Asia and South America.

In contrast to the global trend seen in so many sectors, China is currently not the major player in either the creation of IP or its application in land-based salmon. With the combination of opportunity in China for land-based farming and the depth of their R&D resources, this is one trend we will almost certainly see change in the next few years.

Finally, in what areas are companies filing patents? One measure of this is to look at the International Patent Classification (IPC) of the applications. The IPC is a hierarchical system for the classification of patents which divides technology into ~70, 000 areas. Looking at patent applications in the area of land-based salmon farming we see that the majority of patent activity is in culturing fish, treating water for fish and receptacles for fish – ie inventions focused on the design or operation of land-based farms.

As the industry grows and becomes more established, as we see more new competitors enter, and as established aqua players target their energies at land-based aquaculture we would expect more patents for tailored applications in areas including genetics, health and feed products that are specific to the needs of land-based farming. An example of this trend is WO20217535A1, filed in 2019 by the Danish company Graintec AS, where the applicant specifically makes claims for “a feed manufacturing system for producing an aquaculture feed … adapted for ... recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) …”. Or EP2788110B1, in which Pentair has been granted a patent for ”a method of operating a pump in a [recirculating] aquaculture system”. We predict this trend is set to grow in the next few years.

In summary

IP assets, including patents, are a key factor in creating and maintaining competitive advantage in land-based salmon farming. It is equally important to ensure that a company providing products and services into the land-based market has freedom-to-operate and is not going to be inhibited from selling its products or services as a consequence of competitors’ IP. Patenting activity in land-based farming is still at a relatively nascent stage but we are starting to see a rapid increase of activity in this area as the market becomes more established, competition increases and products are increasingly globalised. It is critical therefore for companies building businesses in this market – whether they be providing solutions or operating farms – to keep on top of developments in the IP landscape and ensure they have a robust IP strategy. This will allow them to leverage their IP assets (and external IP assets) to deliver their commercial goals, while simultaneously being able to respond quickly and effectively to competitor threats.

A final observation

Clearly patenting is only one piece of the story. The Hatch team has been working closely in this area for many years and constantly evaluating new technologies and solutions. One key observation is that – historically – land-based systems utilised quite standard technology which did not differentiate massively between the different system providers. While the first generation were quite simple mechanical systems, what we see now coming on to the market are much more advanced and include digital technologies – in particular IoT, automation and data management/analysis tools.

A key success factor lies in the effective integration of three different players in this digital evolution:

- The land-based technology and equipment providers.

- The providers of digital tools.

- The land-based operators.

Future success will become increasingly dependent on how effectively we can manage the gathering, analysis and deployment of the data generated in these new land-based systems. This will require investment, not only in new technologies and IP, but also in training programmes, processes and systems to support the full potential of these new digital technologies and optimise operational performance.

*Hatch Innovation Services and The Fish Site are both part of Hatch, but The Fish Site retains editorial independence.