With seven seas surrounding the region, including the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea, the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea and the Arabian Sea, the Middle East is not short of sources for fresh seafood. However, total production in the region amounts to only 2.17% of the total worldwide production.

Middle eastern capture fisheries are characterized by a large number of small-scale fishers, with estimates that the small-scale sector provides about 80 to 90% of the total landings.

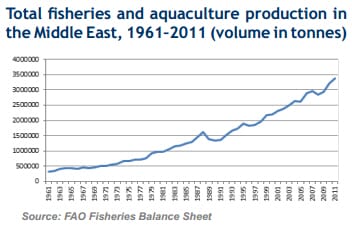

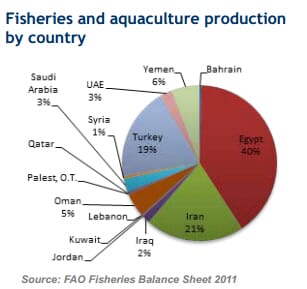

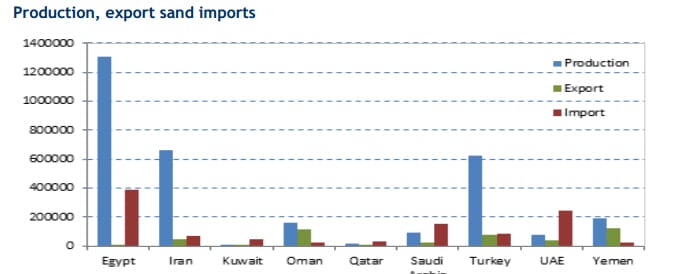

Since 1961, fish production in the Middle East has gradually been increasing at a growth rate of 16%. Egypt is the biggest producer in both capture fisheries and aquaculture, supplying 40% of the total volume. This is followed by The Islamic Republic of Iran (21%), Turkey (19%), Yemen (6%), and Oman (5%). Kuwait, Qatar, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan are the lowest producers.

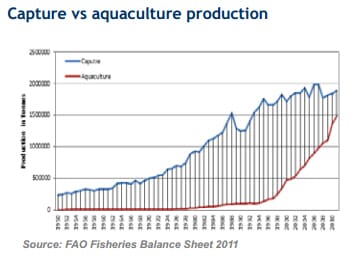

Following global trends, aquaculture has played an increasing role in Middle Eastern production. Indeed, in 2001, out of a total of 2.4 million tonnes produced in the Middle East, 78.6% was from capture fisheries while only 21.4 % was from aquaculture. In 2011, out of a total of 3.4 million tonnes, 56% was from capture fisheries while 44% was contributed by aquaculture.

The main aquaculture producers in the region are Egypt, Saudi Arabia and The Islamic Republic of Iran. In 2011, 72% of all production in Egypt was from aquaculture, while Saudi Arabia and The Islamic Republic of Iran produced 41% and 33% from aquaculture respectively. Aquaculture production is mainly used for domestic consumption.

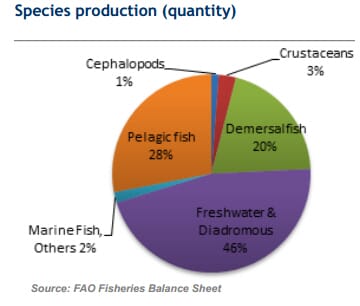

In terms of fish species, fresh water and diadromous fish make up 46% of the species produced in the Middle East. This is mainly due to the aquaculture production in Egypt. In 2011, Nile tilapia production from Egypt contributed to 18% of the total fisheries and aquaculture production in the Middle East at 610 000 tonnes.

Interestingly, if Egypt is not considered, small pelagic species such as sardines, anchovy and mackerel are the highest produced species in the Middle East.

Overall, production in the region is lower than demand. To improve this situation, government support for aquaculture production is growing. In 2013, the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries said it would provide USD 10.6 billion for aquaculture projects with the goal of producing one million tonnes of fish in the next 16 years. Similarly, the Sultanate of Oman announced it would provide USD 1.29 billion for development. The Ministry of Environment in Doha, Qatar, also has plans to boost production and is building a large fish breeding farm and research centers.

Consumption and consumer trends

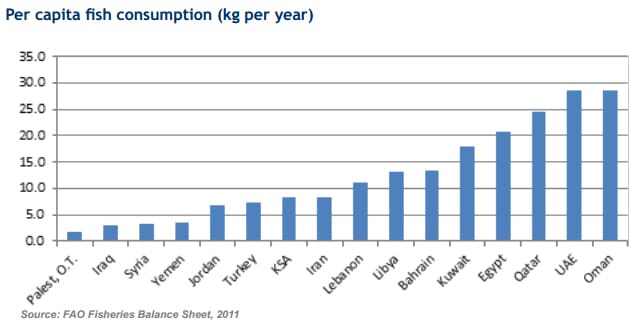

The Middle East, especially the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) region (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and UAE), has seen a substantial rise in per capita seafood consumption. The average per capita consumption for the Middle East in general was 9.9 kg per year in 2010. When taking only the GCC region into consideration however, the average per capita consumption is significantly higher at 14.4 kg per year.

In the UAE and Oman, seafood consumption is one of the highest worldwide, estimated at 28.6 kg per year. Other countries in the region, such as in Qatar and Egypt, also have high seafood consumption rates at 24.5 and 20.8 kg per year respectively.

Overall, small pelagic fish such as sardines and mackerel and large pelagic fish such as tuna and barracuda are the most highly consumed species throughout the Middle East. Freshwater species such as tilapia and Nile perch are also popular and consumed significantly by the Egyptians, Iranians and the Iraqis. The richer oil producing GCC states highly value their local demersal species such as grouper, travelly, emperor and pomfret. Imports of high value seafood products such as scallops, shrimp, lobsters and caviar have increased as a result of the growing economy and tourism sector.

As in other parts of the world, consumers in the Middle East are increasingly purchasing their seafood from supermarkets and shopping malls. Though not widely available, online fish retail stores are also a growing market presence, and work to deliver seafood directly to households in metropolitan cities such as Dubai.

In terms of preferences, an important factor taken into consideration by the Middle Eastern consumer is whether a product is farm raised or wild caught. A large section of consumers prefer wild caught due to the perception that it is more natural, fresher, tastier and healthier. Another emerging trend is consumer interest in sustainability. In the UAE, the government launched a campaign in partnership with the WWF entitled “Choose Wisely”, educating consumers on the sustainability of fish. Similar to other sustainability guides, the campaign provides consumers with a color coded system to provide information about which species are over exploited, considered sustainable or good alternatives. These color codes have been placed in fish retail areas and on restaurant menus in the UAE

Government participation in marketing and trade is limited. The exception is in Yemen, where the government holds strict control over the production, marketing and pricing of fish. Since 2004, it has been mandated that all fish sold in Yemen be sold through official auctions where the government levies a 3% charge plus another 5% service charge on the gross sale value. In other places such as Qatar, Iraq, and Oman, the government has a suggested pricing model in place. In Oman, the government also enforces strict export controls for locally consumed species in order to maintain domestic supply.

Fish and fishery product exports and imports

Exports

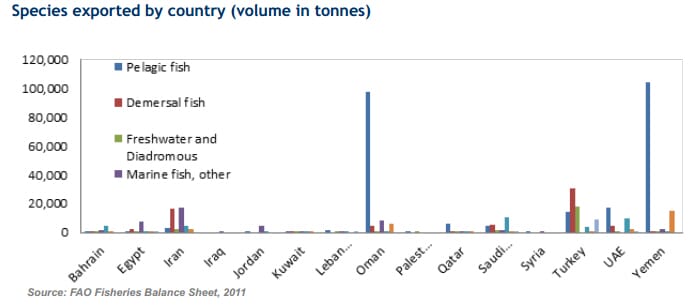

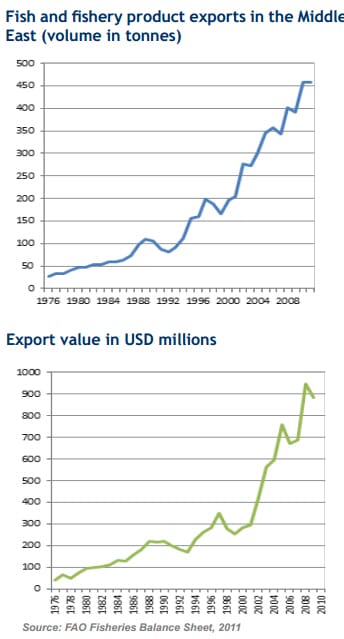

Fish and fishery product exports in the Middle East are minimal in comparison with other major global players. In 2009, exports were from the Middle East were valued at USD 882 million, which was only 0.91% of the global value. Nevertheless, Middle Eastern exports are growing, especially after the 1990’s, when the average growth rate reached 16%. Pelagic fish such as sardines, anchovies, sprats and mackerels are the most exported products from the Middle East.

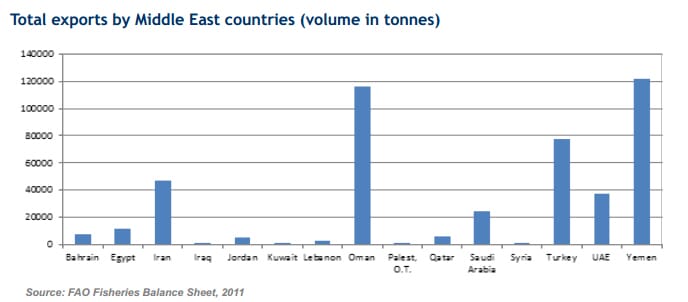

Yemen and Oman, which produce 6% and 5% of the total fisheries production in the region, are the leading exporting nations in the Middle East by volumes. Both countries have long coastlines, a very active fishing sector and low populations, resulting in a high excess of production that is then exported.

Turkey and The Islamic Republic of Iran are the other major exporters. Though Turkey does not export as much in volumes as Oman and Yemen, their export market is valued higher than both. This is mainly due to the fact that the country exports higher value species such as seabass, seabream, trout and bluefin tuna to Europe.

Middle Eastern countries affiliated with the GCC impose very low import tariffs (i.e. 0–5 percent), and as a result, inter-regional trade is strong. Currently, eight countries in the Middle East are allowed to export to the EU, including Egypt, The Islamic Republic of Iran, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Turkey, Israel and UAE.

Imports

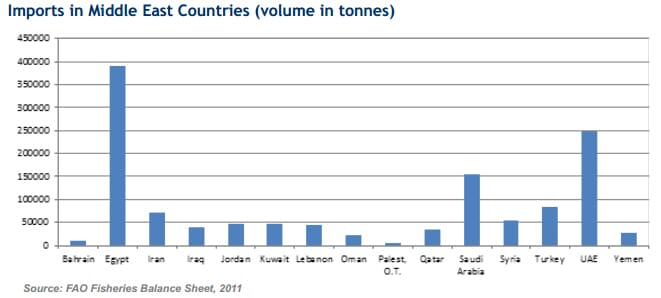

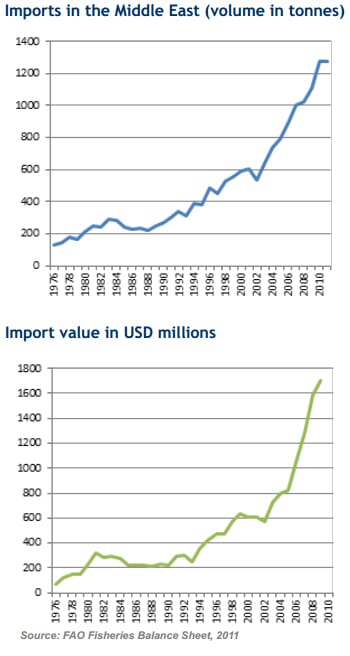

Combined imports in the Middle East are approximately three times greater than combined exports, with import volumes increasing at an average rate of 12.3% since 1980. In 2009, the fisheries import market in the Middle East was worth around USD 1.7 billion occupying 1.69% of the global value.

Countries in the region with large populations and strong economic growth are the biggest importers. Egypt has been one of the drivers of this import growth, as the country has shown an average increase in imports of 12.8% from 1980. UAE has also played a significant role, as it has experienced an annual growth rate of 33.6% since 1999. Egypt, UAE and Saudi Arabia combined take a 62% market share for all imports of fish and fishery products in the region.

Conclusions

Fisheries and aquaculture production in the Middle East is relatively small and remains under developed. Production from the region amounts to only 2% of the total world production. Major producers are Egypt, The Islamic Republic of Iran and Turkey, with Egypt being the largest producer as well as the largest importer.

Oman and Yemen are the main exporters in the region, exporting more than half of their production. The major importers are Egypt, Saudi Arabia and UAE. UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar import several times more than what they produce making the GCC a highly import dependant region.

The Middle East’s demand for seafood has grown significantly due to its economic development, market demand and effective distribution. However, its high seafood consumption and dependence on imports makes the region highly vulnerable to the global seafood market.

With consumption likely to continue to rise, aquaculture has become the most realistic way to meet demand. Recently, government initiatives to enhance domestic production in the region have been increasing with many Middle Eastern governments such as Saudi Arabia, Omen and UAE investing in aquaculture.

As a multicultural, high-income society with a significant number of expatriates and a highly sophisticated retail industry, the Middle East can serve as a testing ground for innovative value added products. Furthermore, with obesity and diabetes as a growing concern in the region, opportunities for healthy value added fish products could be especially promising.

However, processing plants would need to be further developed as currently, most plants are small and do not have strong value addition capabilities. Additionally, processors would have to invest heavily in automatic assembly lines to create these new products.

May 2014