Tony Mazzaccaro had a better year this year than last. After losing more than 20,000 prime market-size hybrid striped bass in the summer of '96, he lost only about 10,000 fish in 1997 - about half a pond's worth - and got the rest to market.

Tony Mazzaccaro had a better year this year than last. After losing more than 20,000 prime market-size hybrid striped bass in the summer of '96, he lost only about 10,000 fish in 1997 - about half a pond's worth - and got the rest to market.

Without intending it, Mazzaccaro's aquaculture ponds have become a biological, sociological and economic laboratory, one that is being watched closely by conservationists, resource managers and the seafood industry.

"These ponds are like a petri dish for the river," quips Mazzaccaro, who owns and operates HyRock Farm near Princess Anne, Maryland. The river is the Manokin, which provides abundant water for his operations; like other Bay tributaries, the Manokin is populated with numerous species of dinoflagellates, algae that include Pfiesteria and other single-celled organisms capable of producing harmful toxins. Mazzaccaro is on full alert against dinoflagellates that come in with the river water.

"It's gotten so I hate summer," he says, with a sweeping exaggeration. From June to October, Mazzaccaro checks his ponds for dissolved oxygen three time a day, seven days a week. "I go out at 5:30 am, 6:00 pm and midnight, every day," he says.

While on guard against potentially deadly invasions from the Manokin, Mazzaccaro must at the same time be careful that nutrient effluent released to the river from fish waste does not degrade the river's water quality. Those nutrients can lead to algal blooms that cause problems both in the ponds and in the river. Fortunately, the HyRock ponds drain into a wetland, which helps to filter out nutrients. Also helpful is the fact that Mazzaccaro drains his ponds once the fish have all gone to market, which means the middle of winter, when biological activity is low in the Bay.

The ecological give-and-take between aquaculture operations and the environment is no small concern in Mazzaccaro's ponds and in aquaculture operations nationally. With an overabundance of nutrients in our coastal waters, environmental organizations caution that the nation's expanding aquaculture operations can become sources of unwanted nutrients if not handled properly. In a recent report on aquaculture entitled "Murky Waters," the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) argues that fish farming, especially in open-water systems such as netpens, can have direct impacts on the quality of coastal waters. At the same time, EDF concludes that aquaculture does not need to be a polluting industry, and calls upon the federal government to encourage environmentally friendly methods for growing fish.

According to Jim McVey, the federal government has already been moving in precisely that direction. The coordinator of aquaculture efforts at the National Sea Grant Program, McVey has helped shape a new initiative in the Department of Commerce that will focus on environmentally sustainable aquaculture, with an initial emphasis on offshore aquaculture, recirculating systems and marine fish enhancement.

The EDF is also calling for further federal oversight of aquaculture, for example, over water netpens as well as regulation of potential pollutants that include chemicals, nutrients and the accidental release of non-native species into local waters. In addition, EDF argues for a program that certifies farm-raised fish grown in "environmentally friendly" systems.

In the midst of concerns about environmental protection and new methodologies, another concern looms large, according to Reginal Harrell, Maryland Sea Grant Extension Aquaculture Specialist. Harrell, who runs an aquaculture research and outreach program at the University of Maryland's Center for Environmental Science (UMCES) Horn Point Laboratory, worries about the bottom line of aquaculture enterprises such as those undertaken with considerable financial commitment by fish farmers like Tony Mazzaccaro.

While Harrell applauds new efforts to develop environmentally friendly aquaculture, he says that "these ideas may get you on the cover of Mother Earth magazine, but you won't see them in Forbes. It all comes down to the economics. Otherwise, why are you doing it?" Like any farmer, fish farmers must, after all is said and done, register a profit. And unlike land farmers, fish farmers have no subsidies to fall back on. If their operations lose money, they're sunk.

The Big Picture

The fledgling efforts to promote aquaculture in the Chesapeake Bay region are being played out against the gigantic backdrop of world fisheries markets. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in recent years, worldwide fish supplies have expanded rapidly. From 20 million metric tons in the 1950s, world fisheries production - including both wild harvests and aquaculture - rose to 109.6 million metric tons in 1994, then 112.3 in 1995. That increase, the FAO reports, is mainly a result of continued rapid growth in aquaculture production, which now accounts for some 27 percent of seafood consumption worldwide.

|

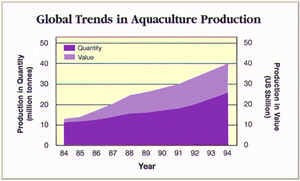

| Between 1984 and 1994, aquaculture production worldwide increased 250 percent and economic value shoed a nearly 400 percent increase (see top graph). |

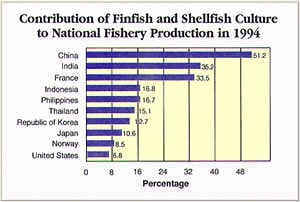

The largest player in this aquaculture increase is not the United States, but China. China, together with India, Japan, the Republic of Korea and the Philippines, account for 80 percent of the world's volume of cultured seafood, according to the FAO report. And the largest species by volume is neither rockfish nor shrimp nor catfish, but carp. "In 1994," reports the FAO, "carp accounted for almost half of the total volume of cultured aquatic products (aquatic plants excluded)."

Though the U.S. does not loom large on the world aquaculture stage, aquaculture plays an increasingly important role here. Based on FAO statistics, nearly all of the catfish and rainbow trout, about half the shrimp and about one-third of the salmon consumed in the U.S. is raised by fish farmers.

A key question in all of this production is whether aquaculture can be both environmentally friendly and economically sustainable.

The Challenge

|

| While U.S. aquaculture production continues to expand, the U.S. accounted for less than seven percent of world aquaculture production in 1994 (see bottom graph). Source: United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and the Environmental Defense Fund. |

There are innovative examples of how science has been put to use in designing sustainable technologies that can relieve such problems as heavy fishing pressure on menhaden. The EDF report points to the Inslee Farm, Inc. of Oklahoma which grows chives in greenhouses using effluent from ponds for raising tilapia, catfish and grass carp. According to EDF, "the farm produces 80 pounds of chives weekly, which are shipped fresh to a wholesaler in Houston."

Waste from aquaculture ponds can also be treated in constructed wetlands, or used to grow desirable plants. "I have always thought it would be good for the Chesapeake Bay to grow plants used for shoreline stabilization," says Harrell. They would use nutrients coming from aquaculture ponds, and provide plants needed for Bay restoration work.

While such integrated systems are attractive, says Harrell, hydroponics require a great deal of work, and additional time and money. In some cases, he says, additional nutrients could be required for particular plants, forcing the farmer to add nutrients at the same time he is trying to remove them. Also, plants must be removed, he points out, or else the nutrients will simply be recycled back into the system.

Removing nutrients in this way has worked well for the Japanese, says McVey, who divide their efforts into "fed" and "extractive" aquaculture. "Fed" aquaculture refers to the raising of species that require additional nutrition in the form of fish food, while "extractive" refers to the culture of species, such as plants, that take up nutrients.

"Unfortunately, we can't grow very much nori or kelp in the Bay area," says Harrell, adding that this is a shame, since the approach is truly "extractive," and provides products, such as agar, which are in great demand. "Once you grow something, you have to be able to market it," he says. Otherwise, the grower is losing money.

The Best Hope

If striped bass culture can provide a livelihood for small farmers in the mid-Atlantic region, while taking pressure off the wild stock, then aquaculture will have gone a long way toward fulfilling its original promise.

"We did not intend our report to be anti-aquaculture," says EDF's Rebecca Goldburg. The report concludes: "Aquaculture need not be a polluting industry. A wide variety of technologies and practices now are available to make aquaculture facilities environmentally friendly...."

Like McVey, Goldburg and her colleagues put considerable faith in the ability of science to solve current technological problems. They call for source reduction of pollutants, and where that is not possible the recycling and reusing of wastes. The least preferred option, says EDF, is disposal of waste in the environment.

McVey and Goldburg agree on other approaches as well, including the use of feeds designed to protect the environment. These include feeds with low fishmeal content, which lessen aquaculture's pressure on wild fisheries, and feeds with nutritional and other characteristics that help aquaculturists minimize food waste.

And finally the EDF report calls for research that can help improve the function of aquaculture and reduce its potentially negative impact on the environment. In the long run, scientific research and technologies are key to the future of aquaculture - if aquaculture is to continue its expansion, we must find new and better ways of protecting against the impacts it is likely to bring.

The potential benefits of such expansion are many: the ready availability of more farmed seafood, greater economic development, reduced pressure on wild fisheries as well as means for enhancing stocks that have already been subjected to the impacts of human activities.

Successfully meeting this potential and minimizing its effect on the environment will take not only the commitment and support of our public agencies, but the efforts of scientists and industry working together.

Source: Maryland Sea Grant - University of Maryland - September 1998.