Crawfish

production can be integrated

with agricultural crop rotations,

and the crawfish life cycle can be

easily manipulated to fit a variety

of cultural situations. Crawfish

aquaculture relies on control of

pond hydrology to simulate optimal

wet and dry conditions occurring

in natural riverine and wetland

habitats. Crawfish grow and

mature during the wet or flooded

cycle and survive the dry periods

by digging burrows. Crawfish

ponds are filled in the fall to coincide

with peak spawning of

females in burrows. When burrows

are filled with water, adults

and juveniles leave the burrow

and distribute themselves

throughout the pond.

Crawfish

production can be integrated

with agricultural crop rotations,

and the crawfish life cycle can be

easily manipulated to fit a variety

of cultural situations. Crawfish

aquaculture relies on control of

pond hydrology to simulate optimal

wet and dry conditions occurring

in natural riverine and wetland

habitats. Crawfish grow and

mature during the wet or flooded

cycle and survive the dry periods

by digging burrows. Crawfish

ponds are filled in the fall to coincide

with peak spawning of

females in burrows. When burrows

are filled with water, adults

and juveniles leave the burrow

and distribute themselves

throughout the pond.

Crawfish production systems

Crawfish ponds can be singlecrop and rotational. Single-crop ponds are in the same location every year with a continuous management scheme. Rotational ponds are those in which crawfish are rotated with other crops. Rotational production also can mean rotating the physical location of the field in which crawfish are grown.

Single-crop ponds

Single-crop ponds are constructed and managed solely for the purpose of culturing crawfish. Crawfish can be harvested in single- crop ponds 1 to 2 months longer than in some rotational systems because there is no overlap with planting, draining, and harvesting schedules of other crops. The three principal types of ponds are cultivated forage ponds, naturally vegetated ponds, and wooded ponds. The following crawfish culture cycle is applicable to each of the three types:

- April - May: Stock 50 to 60 pounds of adult crawfish per acre (new ponds only).

- May - June: Drain pond over a 2- to 4-week period.

- June - August: Plant crawfish forage or manage natural vegetation.

- October: Reflood pond (based on air temperature).

- November - May/June: Harvest crawfish.

- May/June: Drain pond and repeat cycle without restocking crawfish.

Cultivated Forage Pond. These

are permanent ponds where a cultivated

forage crop is established

annually (Fig. 1). Ponds are usually

tillable to facilitate planting and

management of rice or other agronomic

crops. Ponds are often

designed with baffle levees and

recirculation systems to improve

production. Because they are

intensively managed, cultivated

forage ponds generally have the

highest yields (pounds of crawfish)

per acre.

Cultivated Forage Pond. These

are permanent ponds where a cultivated

forage crop is established

annually (Fig. 1). Ponds are usually

tillable to facilitate planting and

management of rice or other agronomic

crops. Ponds are often

designed with baffle levees and

recirculation systems to improve

production. Because they are

intensively managed, cultivated

forage ponds generally have the

highest yields (pounds of crawfish)

per acre.

Naturally Vegetated Ponds. These

are marsh impoundments and

agricultural lands managed to

encourage the growth of naturally

occurring vegetation. Marsh

ponds are typically constructed in

wetland areas with large amounts

of organic matter in the soil,

which may lower water quality

and decrease crawfish production.

Although these ponds may be

managed exclusively for crawfish,

they are generally not recommended

for commercial crawfish

production because yields are

inconsistent.

Agricultural lands unsuited for

growing grain crops because of

poor drainage or soils are sometimes

used for naturally vegetated

crawfish ponds. It can be

difficult to establish an adequate

forage base with the proper balance

of aquatic and terrestrial

plant species. Water management

also can be a problem. However,

these kinds of ponds can sometimes

be effective low-input production

systems.

Wooded Ponds. These ponds are

built on heavy clay soils in forested

(cypress-tupelo swamps)

areas near drainage canals. Water

temperatures tend to be lower

because of shading. Wooded

ponds have poor stands of vegetative

forage; leaf litter provides

the bulk of forage. However,

rapid leaf fall can cause water

quality to deteriorate because

oxygen may become depleted as

leaves decay. Trees hinder water

movement and obstruct access by

harvesting boats, so they are

sometimes removed. More

intense water management is

needed to maintain good water

quality in wooded impoundments.

Wooded ponds usually produce

fewer pounds of crawfish per

acre than other production systems,

but large crawfish may be

produced at a profit. After several

years of alternate flooding and

drying, wooded ponds lose many

hardwood trees. A natural vegetation

base of terrestrial grasses

and aquatic plants subsequently

develops, which improves crawfish

habitat. There are some positive

aspects of wooded ponds,

including the potential for waterfowl

hunting, the low initial

start-up costs, and the ability to

selectivly remove unwanted

vegetation.

Rotational ponds

The most common rotational

pond systems are rice-crawfishrice,

rice-crawfish-soybeans, and

rice-crawfish-fallow. In the ricecrawfish-

rice crop rotation, both

rice and crawfish crops are harvested

annually. This is commonly

referred to as double cropping. In

the rice-crawfish-soybeans rotation,

farmers produce three different

crops in 2 years. In the ricecrawfish-

fallow rotation, farmers

leave the field fallow between

rotations to control weeds and

prevent crawfish overpopulation.

In this system, crawfish are produced

in different physical locations

from year to year.

Well managed crawfish rotation

systems use farm resources efficiently,

diversify production, and

add income for many farm families.

However, maximum production

from each crop usually is not

achievable. Some management

compromise is necessary from one

or all crops.

Rice-Crawfish-Rice. Rice fields

are the most readily adaptable

areas for crawfish culture. The rice

farmer can use the same land,

equipment, pumps and farm labor

that are already in place. After the

grain is harvested, the remaining

stubble is fertilized, flooded and

allowed to re-grow. This ratoon

crop is the forage base for crawfish

production. Maximum crawfish

production is sometimes compromised

because rice culture

takes precedence over crawfish

production. For example, rice production

often requires the use of

pesticides and different water

management than is optimal for

crawfish. These ponds are usually

drained in early spring (March 1

to April 1) so that rice can be

replanted. This shortens the crawfish

harvest season 1 to 2 months

and reduces potential crawfish

yield. A typical time-table is as follows:

- March - April: Plant rice.

- June: At permanent flood (rice 8 to 10 inches high), stock 40 to 50 pounds of adult crawfish per acre.

- August: Drain field and harvest rice.

- October: Re-flood rice field.

- December - April: Harvest crawfish.

- March - April: Drain pond and replant rice (restocking of crawfish may or may not be necessary).

- March - April: Plant rice.

- June: Stock 40 to 50 pounds of adult crawfish per acre at permanent flood.

- August: Drain field and harvest rice.

- October: Re-flood rice field.

- December - May: Harvest crawfish.

- Late May - June: Drain pond and plant soybeans.

- October - November: Harvest soybeans.

- November - March: Re-flood pond and harvest crawfish (or leave field fallow).

- March - April: Plant rice (restocking of crawfish is probably necessary).

- March - April: Plant rice.

- June: Stock 40 to 50 pounds of adult crawfish per acre at permanent flood.

- August: Drain pond and harvest rice.

- October: Re-flood rice field.

- December - June/July: Harvest crawfish.

- July: Drain pond.

- August - March: Fallow.

- March - April: Plant rice.

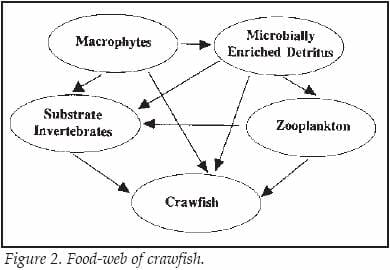

Forages

In a natural ecosystem, crawfish

eat a variety of plants and animals.

Crawfish prefer aquatic

invertebrates but will feed on

detritus and growing vegetation.

Detritus, or decomposing organic

material, is the base of the complex,

self-sustaining food system

required in crawfish culture

(Fig. 2).

As organic matter decomposes, it

becomes "coated" with bacteria,

other microorganisms, and small

invertebrates that increase its

nutritional quality. Larger aquatic

fauna such as insects, worms,

clams, snails and zooplankton

feed on the enriched decomposing

vegetation. It is these animals that

make up the major part of the

crawfish diet. Crawfish eat very

little living plant material, but rely

on the small invertebrates that

live on or near plant stems. Some

plant seeds may also be important

food resources.

Crawfish production can use

planted and cultivated forage

crops or voluntary natural vegetation.

The forage must provide

detritus to the underwater foodweb

consistently throughout the

growing season. Many aquatic

plants, such as alligatorweed

(Alternathera philoxeroides), perform

this task poorly but can provide

substrate and cover for other

organisms that are food for crawfish.

Cultivated crops are more

consistent from year to year and

usually provide for a more consistent

supply to the underwater

food-web.

Cultivated forages

Cultivated forages provide a controlled,

consistent supply of detritus

that results in good crawfish

yields. Planting an agronomic

crop allows farmers to control the

type and amount of available forage.

Forage density is more predictable

with an agronomic crop

because cultural practices are well

established. Research has shown

that potential crawfish yield can

be increased 2- to

3-fold with good

stands of cultivated

forage as compared

to using

natural vegetation

only.

Rice (Oryza sativa)

is the preferred

forage for crawfish.

Rice is less

detrimental to

water quality than

terrestrial plants.

It can be planted

for grain production,

with the

post-harvest residue and regrowth

serving as crawfish forage,

or it can be planted solely as a

crawfish forage with no intent to

produce grain.

When selecting a rice variety for

crawfish production consider the

culture system (rotational or single

cropping), forage biomass production,

lodging characteristics,

disease resistance, adaptability to

local environmental conditions,

and rice ratoon potential. Check

with your county Extension agent

for a list of recommended rice

varieties to use solely as planted

forages.

Rice for Grain and Forage.

Proper variety selection and cultivation

practices will ensure optimum

grain yield, but several

other considerations are important

when crawfish production is to

follow. Timing of the grain harvest

is determined by the time of

planting, the variety, and the

weather; it will also affect subsequent

forage production. For best

results, the ratoon crop should

reach maximum forage production

after the harvest but should

not reach full maturity. Ratoon

crops that do reach full maturity

wither (senesce) and often become

prematurely depleted, causing

forage shortages.

Huge amounts of loose plant

stalks and leaves remain in the

field after grain harvest. This

residue should be reduced before

the field is re-flooded or it will

cause water quality to deteriorate.

A straw chopper on the rice combine

will chop up the excess straw

into smaller pieces that decompose

more rapidly during the

weeks before re-flooding. Or, the

harvest residue can be bailed or

burned.

Dead plant material can not be

effectively stockpiled in a pond.

The only way to increase longterm

supply is to encourage

regrowth of rice stubble after the

grain has been harvested. A light

application of nitrogen (20 to 40

pounds of nitrogen per acre) can

be applied shortly after harvest.

The field should then be flushed if

adequate moisture is not available.

Timely flushing of the field

will prevent the loss of nitrogen

and encourage rapid stubble

regrowth.

Rice for Forage. It is often desirable

to grow a stand of rice as forage

only. The variety chosen

should produce high vegetative

biomass, be resistant to lodging

and disease, senesce slowly, and

persist throughout the crawfish

production season. Forage rice

should be planted early enough to

allow maximum vegetative

growth without reaching full

maturity. Flooding immature rice

results in better water quality

because there is less decomposing

organic matter at the time of fall

flooding. Rice that does not reach

full maturity persists longer under

flooded conditions and is more

likely to generate additional

growth in the spring.

The potential and requirements

for rice production to be adequate

for crawfish culture vary from

area to area. Follow the recommended

practices for your region.

In general, rice is either drilled or

broadcast planted in well-tilled

seedbeds at rates ranging from 90

to 120 pounds per acre. Although

rice requires considerable water

for growth, commercial rice producers

maintain a shallow flood

mainly for weed control and better

fertilizer management. This is

not necessary when growing rice

for crawfish forage; in fact, standing

water on the seed or seedling,

if it is too hot, can result in poor

stands. Rice may be irrigated during

dry periods. Fertilizer usually

is required for good rice growth

and development; soil should be

tested first to determine its fertility.

A common application rate is

60 to 80 pounds per acre of nitrogen

(N) and 30 pounds per acre of

both phosphorus (P) and potassium

(K). Herbicides are not necessary.

Some weed invasion is not

harmful (and may even be desirable)

in crawfish crops. Consult

knowledgeable professionals for

assistance.

Sorghum-sudangrass. Good rice

stands may be difficult to achieve

in some geographical regions and

under some environmental conditions,

especially during late summer

in the southern U.S. Other

forage crops, such as sorghumsudangrass

hybrid (Sorghum bicol-

or), may be a good alternative for

crawfish forage (Fig. 3).

Sorghum-sudangrass seed is

available from most farm suppliers

and seed dealers. It grows

rapidly, produces larger quantities

of vegetative matter than rice, is

drought resistant, and may be

more reliable than rice for late

summer stand establishment.

Sorghum-sudangrass tends to

persist longer than rice in flooded

crawfish ponds, which makes

more forage available during the

latter part of the crawfish growing

season.

Sorghum-sudangrass seed is

available from most farm suppliers

and seed dealers. It grows

rapidly, produces larger quantities

of vegetative matter than rice, is

drought resistant, and may be

more reliable than rice for late

summer stand establishment.

Sorghum-sudangrass tends to

persist longer than rice in flooded

crawfish ponds, which makes

more forage available during the

latter part of the crawfish growing

season.

Sorghum-sudangrass should be

used only in ponds where a forage

is planted in late summer.

Target planting dates should be

early August through early

September in the deep South.

If planted too early, sorghumsudangrass

is likely to mature

before flood-up, which can be

detrimental to water quality when

plants lodge or large numbers of

leaves sluff off into the water.

However, planting should not be

postponed too long because cooler

weather and the shorter days of

early fall may inhibit plant establishment

and growth. Advanced

stands of sorghum-sudangrass

should be cut to a 1- to 2-inch

stubble in early to mid-August

and baled.

Sorghum-sudangrass seed can be

drilled or broadcast onto moist

soil. Drilling is preferred and is

less risky. Seeding rates should be

20 to 25 pounds per acre for

drilling and 25 to 30 pounds per

acre for broadcasting. Optimum

germination temperature is 70 to

85 degrees F. Seeds need adequate

soil moisture to germinate, but the

seedlings are fairly drought tolerant

once they are established.

Sorghum hybrids are sensitive to

very low soil pH but seem to tolerate

a pH as low as 5.5 without

problems. Fertilizers can significantly

increase growth and the

vegetative biomass of sorghumsudangrass.

Follow the

Cooperative Extension Service

fertilizer and culture recommendations

for sorghum-sudangrass

in your area.

It may be desirable to mow trapping

lanes in the pond just before

flooding in the fall, especially if

sorghum-sudangrass was planted

early. Tall plants restrict vision

from a boat during early-season

harvest.

Pesticide toxicity

Be careful using pesticides in or near crawfish ponds; crawfish are very sensitive to most chemicals and carelessness can quickly eliminate production. Read the label of any chemical or compound before using it.

Natural vegetation

Natural voluntary vegetation is

usually the least expensive to

establish and can sometimes be

satisfactory as a forage crop; however,

it is often unreliable and

insufficient for maximum crawfish

production. When flooded,

voluntary terrestrial grasses and

sedges usually decompose rapidly.

This reduces water quality and

provides short-lived detrital

sources. Aquatic and semi-aquatic

plants such as alligatorweed

(Alternathera philoxeroides) and

smartweed (Polygonium spp.) are

superior to terrestrial grasses

because they continue to live

when flooded. During much of

the season little material is cast

from these plants to form detritus.

However, during the winter the

emergent parts of the plants die

and form large amounts of detritus,

usually at a time when low

water temperatures reduce feeding

by aquatic organisms.

The three major disadvantages

of using natural vegetation are:

(1) stand density varies with location

and time of year, and is

unpredictable from one year to

the next; (2) cultural practices for

natural plant species are not well

understood; and (3) many natural

plants are considered noxious

weeds and are unwanted where

agronomic crops will be grown in

subsequent years. Despite these

obstacles, ponds with an appropriate

mixture of aquatic, semiaquatic

and terrestrial vegetation

do occasionally produce good

crawfish crops.

Forage production is one of the

most important components of

crawfish production. This publiction

has outlined the basics of forage

based production systems for

crawfish in the Southeast. For

more information on crawfish

production contact the Extension

Fisheries/Aquaculture Specialist

in your state.

Source: Southern Regional Agricultural Center and the Texas Aquaculture Extension Service - October 2004