“Selling the shovels” has its adherents in aquaculture, too. Investors rightly see an enormous future in aquaculture, and the sector’s having an exciting moment as investment piles into emerging feeds science, novel production systems and innovative new tools to sharpen value chains. But the real scarcity today isn’t shovels, but an acute shortage of miners. Marine aquaculture production represents seafood’s biggest opportunities for profits and impacts, but barriers to investment are keeping a tight lid on its growth. Until production takes off in the areas where it can meet the enormous scale of demand, seafood’s most promising field – from both a commercial and impact perspective – won’t meet its true potential.

Gold in them hills

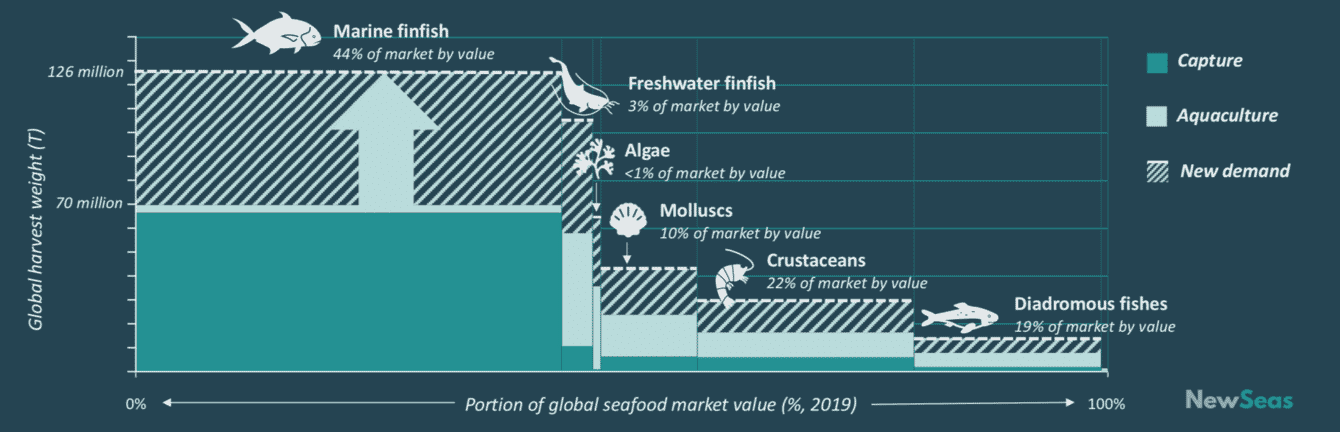

The rewards for unlocking bottlenecks in marine aquaculture are sensational. Seafood demand is set to nearly double over the next 30 years, which means that aquaculture output will have to triple. For marine finfish – the biggest category of the seafood market, but the subject of just 3 percent of today’s aquaculture production – supplying new demand will require ramping up annual production to 60 million tonnes – up from a current output base of just 3 million tonnes. That’s a new industry that’s nearly 25 times larger than today’s global salmon sector.

© NewSeas (data source: FAO FishStat)

Impact rewards are equally enormous and the need is urgent. Overfishing is already the single biggest driver of marine vertebrate extinctions. Demand growth without commensurate increases in supply raises seafood prices and adds to the incentives to catch the last fish – as varied regulatory regimes, uneven enforcement resources, a price-sensitive market and globally opportunistic fleets combine to form powerful means that are extremely difficult to control. Scaling up a more sustainable source of supply – and fast – is the single most powerful tool we have to ensure a resilient future for our oceans. The new industry’s leaders will also be able to set its standards.

Challenges to investment

For investors hoping to ride aquaculture’s huge growth wave, the appeal of “industry ecosystem” investments is obvious. A 2018 Credit Suisse report summed it up nicely: investors are strongly interested in aquaculture and other areas of the “blue economy”, but they have limited sector-specific knowledge and the projects that cross their desks mostly look uninvestable.

The first difficulty is around profile. Aquaculture’s production footprint continues to be concentrated – with the notable exceptions of salmon and shrimp – in relatively low-value products. Measured by harvest volume, algae and freshwater finfish dominate the industry, but in 2019 they made up just 1 percent and 3 percent respectively of seafood by traded value.

Impact-minded investors are attracted by the light ecological footprints of low trophic species and also by the low capital costs which make these systems accessible to smallholder farmers. Unfortunately, the production of low trophic species does little to offset the demand for the marine finfish targeted by overfishing. Meanwhile, those same low capital costs also result in a ticket size that’s too small to support investment’s associated due-diligence and structuring costs. Low barriers to entry undercut paths to significant financial profitability.

Secondly, evaluating farming risk can appear challenging. Changing dynamics around regulation, new geographies of demand, global cost-competitiveness and warm-water requirements of many of the best candidate species all make middle-income countries the new centres of scalable production. But these countries come with unique financing climates and require an approach to investment that isn’t intuitive to many developed-world financiers – including those who bankrolled salmon’s success.

Also, financiers and farmers are distinctly different animals. Mainstream financiers rightly identify a shortage of experience necessary to accurately evaluate production risks. Farmers often have a poor understanding of investors’ expectations and of what a project requires to be finance-ready. The two groups are further separated by a completely different perspective and language when it comes to discussing things like risk and investment structure.

Finally, investment in production is hampered by aquaculture’s dirty footprint in the collective public imagination. It’s not that the industry didn’t earn that reputation: especially in the early years of its learning curve, hugely damaging mistakes were made. Some continue to be repeated by irresponsible operators. But, especially in high-value sectors like salmon farming, practices now widely adopted by the industry result in more reliable production performance and create some of the most sustainable food choices on the menu. Nevertheless, it’s still easy to understand why investment managers feel reluctant to stick their necks out in an era of investor activism and social media.

Supply chains that are short of supply

The collective action of investors has been to engage – but at the periphery. Novel land-based systems come with a particular technical risk profile (as recent headlines remind us), but one upside is that these projects can be conveniently built in the investor’s backyard. And while high production costs of many such systems limit business cases to relatively isolated high-value sub-segments of the market, such niches do exist.

Supply chain investments like feeds, health and technology innovations are also popular – much like the shovels and blue jeans of the old Far West. Correctly picking and backing the right companies can result in success: for financial returns, as well as wider sector efficiency improvements. The trouble is that commercial success and the relevance of impacts both rely on growth of the underlying production industry. Value-chain improvements are always welcomed, but it’s not a shortage of proven production systems that is keeping the industry from expanding to its potential. The real bottleneck is a shortage of farms. Without a strong production-based foundation, a limited universe of value chain opportunities combined with a financial climate flush with cash makes it increasingly difficult to pick the winning models. It also raises a risk of valuation bubbles.

Future solutions

There’s a way out – but it will take creativity and courage.

The project finance industry has a track record of bringing trillions of dollars of investment into emerging and frontier market projects with high capex and long cash tails: in other words, businesses with profiles very similar to the most proven and scalable forms of aquaculture. I come from an emerging market project finance background and have seen firsthand how a structured approach – with a focus on mitigating, assigning and pricing risk – opens paths to investment in some of the world’s most difficult-to-finance markets. It requires an unusual amount of time and energy upfront, but we’ve seen in our business, NewSeas, that through this approach institutional investors are excited to participate in new aquaculture production businesses that could otherwise not be financed.

Sustainability certification can also play another important role. Most financiers can’t be expected to be fluent in the industry’s production footprints – but they sure are aware of their reputational risks if their investees behave badly. Rigid third-party sustainability certification standards are a valuable tool. By effectively assigning key sustainability risks to trusted certification bodies who deeply understand the science and who rigorously control the process, investors can sleep much easier. Sustainability certification also helps to reduce other risks: because meeting these standards means farmers are complying with established best practices, lowering the risk of technical performance failures, while the labelling improves their product’s marketability.

“Industry scale” isn’t intuitively popular for investors focused on generating positive impacts. But no term better describes the nature of threats to our oceans or the scale of the necessary solutions. Similarly, enormous commercial potential attracts tremendous amounts of capital to create new and scalable solutions.

The salmon industry’s unsteady early track record was in part a result of a non-existent industry ecosystem with few resources for innovation. As that industry achieved scale, huge improvements followed: in the time since FCRs fell, health indicators rose, pollution management improved and wild fish content in feeds was reduced. Wider marine finfish aquaculture will benefit from an enormous head-start by riding on the salmon sector’s coat tails, and we can count on its industrial scale to ensure further advancements as the sector matures.

Eureka!

It turns out that even the traditional gold rush tale isn’t quite accurate: yes, fortunes were made by a few clever folks selling supplies once mining went bonkers, and many miners – especially those who entered the game late – left without profits. But early entrants did quite well: it’s been estimated that average earnings of a typical Forty Niner clocked in between ten and 15 times the wages of American labourers who stayed back east. Not a bad bet.

Consumer demand always gets its way, so it’s got to be said that, from a narrow commercial perspective, aquaculture production looks like another convincing bet in any case: given the finite nature of wild fish stocks, the enormous expansion of farmed seafood production is inevitable. What’s less certain is whether this massive new industry will be built on a foundation of sustainability, and whether it will grow fast enough to avoid the worst results of overfishing. Positive outcomes will only happen with intent. Investors at the forefront of new production will participate in an extraordinary market opportunity – and will set the terms for how this new industry develops.