Speaking at Aquaculture Europe in Berlin this week, Raminta Kazlauskaite from the University of Glasgow gave a fascinating talk on the development of how her team has created an artificial salmon gut system, called SalmoSim.

She kicked off the presentation by explaining how the system, when fully developed could help to reduce the cost of feed trials for the €13 billion salmon farming sector, which consumes about 11 percent of the aquafeeds produced globally.

“We got some insider information that do to just one field trial for one feed additive costs around £150,000,” she explained, “and there are only around 10 feed testing sites around Europe, leading to very long wait times for trials. Feed trials also tend to take quite a long time, as they usually wait for fish to double in size, which takes up to 6 months.”

Given that the composition of the salmon gut microbiome impacts how the fish absorbs nutrients, its metabolic rate and its growth rate, the project aims to create an artificial fish gut to use for testing microbial fermentation of novel feeds, as well as the effectiveness of pro, pre and synbiotics.

“Our proposal is that we can avoid all these feed trials by using our system, SalmonSim. What is SalmoSim, it’s an artificial salmon gut system. I know it sounds a bit science fiction, but it’s up and running right now”.

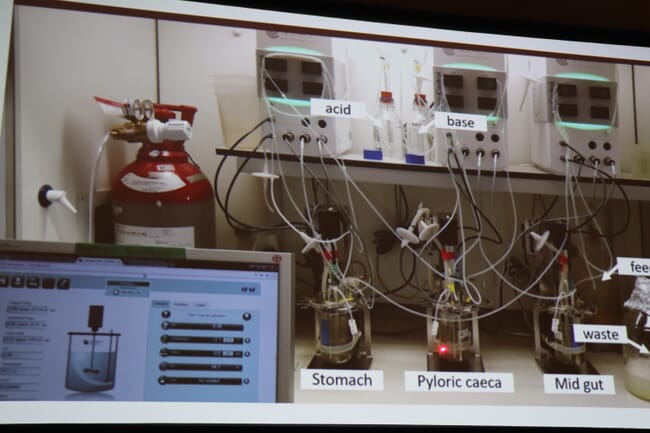

Kazlauskaite went on to explain how they had created three bioreactors, to replicate the conditions in the three sections of the salmonid digestive tract: the stomach, the pyloric caeca and the mid-gut. Once they had ensured that conditions in each three chambers mimicked those of a real salmon’s digestive tract they have been able to conduct a number of different trials.

“We can see what happens if you add a new [in-feed] drug or a new feed ingredient into the system we can see what happens. We can also look at compound stability, such as drug stability or EPA and DHA analysis, and see how the different bacterial communities form these nice groups again.”

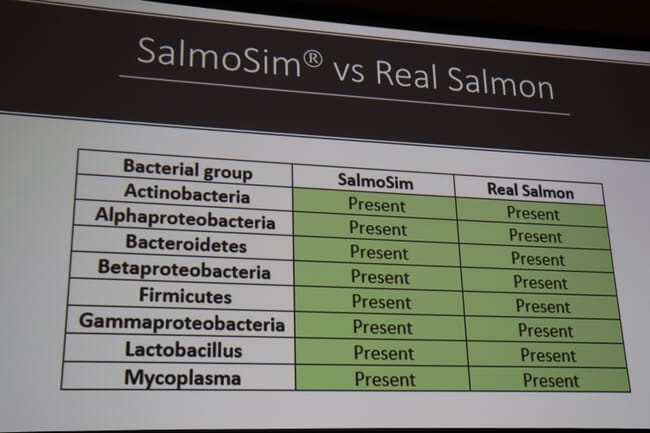

As the system has developed Kazlauskaite has since been able to validate the technology by comparing the results obtained in the SalmoSim to those obtained in a feed trial by Mowi in Norway – looking at how SalmoSim and real salmon reacted to two types of feed – one of which had zero fishmeal content.

The preliminary results, of analysing how the bacterial communities in both the salmon and the simulator behaved under the two different feeding regimes, said Kazlauskaite, didn’t completely match but were “quite encouraging”.

While, as she admitted, the system still needs some fine tuning, trials suggest that it is not far off being ready for commercial launch and that it can, in time, be applied to a range of purposes.

“We have the SalmonSim system and it can help you a lot. It can be adapted to a range of applied questions, although it’s important to stress that it’s not a replacement for feed trials, but a tool to enhance them and to reduce costs,” she emphasised.

Uses, she noted, include testing alternative feeds, testing feed batch consistency, testing in-feed medication over a much shorter period (20 days instead of up to 6 months), testing whether new drugs survive the conditions within any of the salmon’s three digestive compartments, and testing the impact of prebiotics on microbial growth too.

“If you have many different feed additives you can test them one at a time in the SalmoSim and then reduce the number you need to test in field trials, which makes the feed trials much cheaper,” Kazlauskaite reflected.

Looking ahead Kazlauskaite explained how the team plans to make the system more sophisticated so that it can perform functions such as digestibility trials.

And as for the reaction from the industry?

“We’re currently collecting suggestions and offers but there’s already a queue of people waiting to use it and we’re hoping to commercialise it soon,” Kazlauskaite explained.