Despite a large number of freshwater reservoirs that could be used for farming fish, and a tropical climate favourable to rearing species such as tilapia, aquaculture in Brazil is still in its infancy. With few large players, the industry needs further development in terms of production technology and equipment to reach its full potential. But Alexandre Pulino, director of development at Fisher Piscicultura, believes that Brazil can become one of the world’s leaders in aquaculture. Pulino has even more reason to be optimistic, as he is confident that a new production system being developed by his company is likely to contribute greatly to the evolution of tilapia farming in Brazil.

“Our production and feeding system is a tentative step towards addressing the demand for aquaculture technology suited to Brazilian characteristics,” says Pulino. “The aim of the system is to support expanding tilapia production. One of our partners installed and managed the operation of a large-scale project for tilapia production (producing 3,600 tonnes a year) with regular-size cages (18m3) and manual feed. He had over 1,000 cages and around 50 to 60 people feeding, classifying and handling the fish and cages. This was extremely inefficient in terms of workforce and made it hard to manage production properly so we decided to try something new.”

After a research project that began in 2013, the Fisher Piscicultura team spent a year designing the new system. The first prototype was produced in 2014, followed by the first field tests in 2015. By 2017, cage production had been tested to its full capacity with support from Agência Paulista de Tecnologia dos Agronegócios (APTA), the São Paulo agribusiness technology agency. Funds were partly provided by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), the São Paulo State Research Foundation.

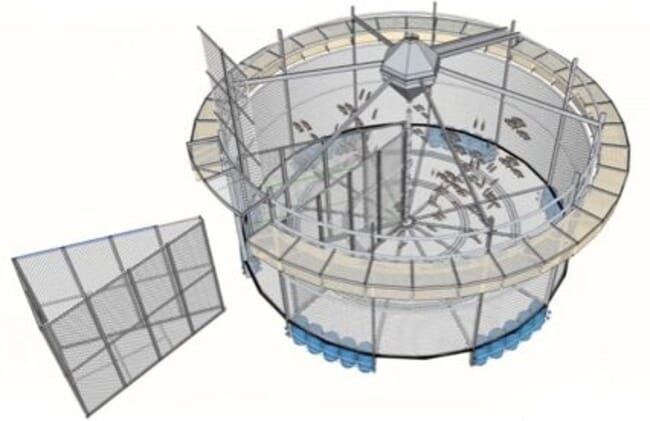

The new production system consists of a series of circular, floating cages made of aluminium wire mesh, with central pivots and rotating screens. Usually, tilapia are moved from one pen to another when they reach a certain size to make way for a new batch of smaller, younger fish. But this involves removing them from the water, leading to stress and a high number of deaths. Under the new system, different sized screens are used to separate the fish while keeping them in the water, thanks to a door and a slice cage (a floating pie slice- or wedge-shaped mesh container) which can be inserted into the main cage. A pivoting gate is then used to take the separated fish out and into a container, which is then floated over to another cage where they are released. During cleaning and maintenance, the cages are lifted out of the water with plastic rafts, while a ring of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles keeps them on the surface of the water during farming.

In the centre of each cage is a feed silo equipped with a solar-powered timer. A device at the bottom of the silo releases the feed automatically, in line with the feeding programme that’s currently in place. As the fish are periodically sampled to measure for growth, a feed curve is programmed and adjusted from time to time. The feeding device also measures water temperature and dissolved oxygen, allowing operators to correct the feeding curve accordingly.

A pivoting gate is then used to take the separated fish out and into a container, which is then floated over to another cage where they are released

“Each cage has 450m3 of internal volume,” says Pulino. “The inner measurements are: 12m in diameter and 4m high on the inside, and 14m in diameter and 7m high externally. Each cage is designed to produce 33 tonnes of tilapia per nine-month cycle. They receive around 80,000 juveniles at the beginning of the cycle, and these are divided into two cages during production.”

The new system also allows more control over feed quantity. According to Pulino, feed is responsible for over 70 percent of production costs in conventional tilapia farms. His system distributes feed 48 times a day – every 15 minutes from 6am to 6pm. The team’s designers say that feeding the tilapia like this often keeps them satiated and makes them convert feed into weight gain more efficiently. As a result, farm operators can reduce the amount of excrement produced by the fish, and the fish are better able to digest their food.

“Our system also minimises competition for feeding, resulting in less stress, lower mortality and a more uniform cohort,” says Pulino. “By providing the right amount of feed in a high frequency, we have been able to obtain good fish growth and an optimum feed conversion rate of below 1.5:1 – the local industry best practice.”

Pulino believes there are various reasons for the reduced mortality rate, which in trials on using the system on his own farm dropped from 20 percent to around 7 percent.

“First, we do not take the fish out of the water during grading,” he says. “Second, there is less competition for food because we feed at a high frequency. Third, the big cages are more stable so the net does not rub against the fish as small cages do. This rubbing effect can harm the skin of the fish and take away the mucous that protects them against bacteria or infections.”

So far Fisher Piscicultura has built 11 of these units but the next step is to commercialise the invention by establishing a production line to manufacture them. Although the system was designed for tilapia production, Pulino says that other aquaculture producers could also benefit.

“It could be used for other fish raised in big freshwater reservoirs,” he says. “In Brazil we have other species – for example pacu and tambaqui – that could also be farmed in these cages.”

The third phase of the project is also about to begin: to start selling the equipment in Brazil and abroad. Hopes are high that Fisher Piscicultura’s system will be an ideal form of cage technology for large-scale tilapia projects that will allow operations in Brazil to grow.