The optimisation of hatcheries may be key to progressing the West's nascent seaweed industry © SINTEF Ocean

Perhaps it has never crossed your mind, but whenever you see pictures of lovely, lush seaweed being harvested from a farm, this is the result of a meticulous process that began many months (sometimes years) earlier, with the production of healthy seedlings.

There is a saying in seaweed cultivation that I first heard from Paul Dobbins (World Wildlife Fund) that sums this up nicely: “Hatchery is destiny”, which alludes to the fact that the hatchery phase is the foundation for all that follows in seaweed cultivation. Despite this, what happens in the hatchery may also be one of the least understood stages of the cultivation process. After all, many seaweed farmers in the West source their seedlings from a seedling supplier and may see the hatchery as something of a black box.

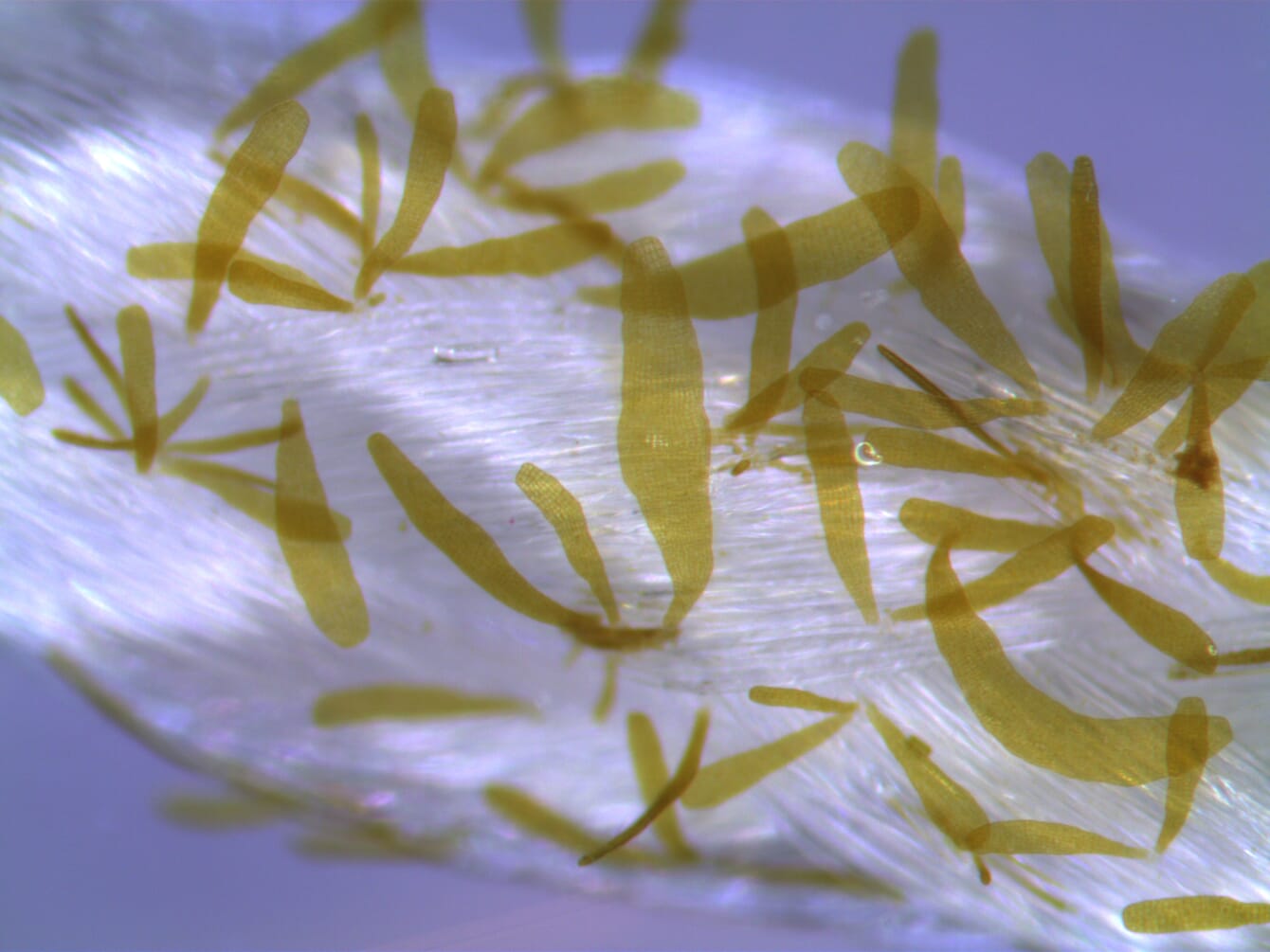

Fundamentally, the hatchery’s role is to produce seedlings. It involves three key steps: inducing fertility in parent plants, extracting seeds, fertilising those seeds and sowing them onto some kind of substrate. Traditionally, those seeds are sown onto rope in a nursery to incubate them during their most vulnerable juvenile stage, allowing for holdfast attachment and for early growth to occur in a controlled environment. Increasingly, there is interest in skipping the nursery stage entirely and applying seedlings directly to the cultivation rope prior to deployment at sea, hence the term direct seeding.

© Seaweed Solutions

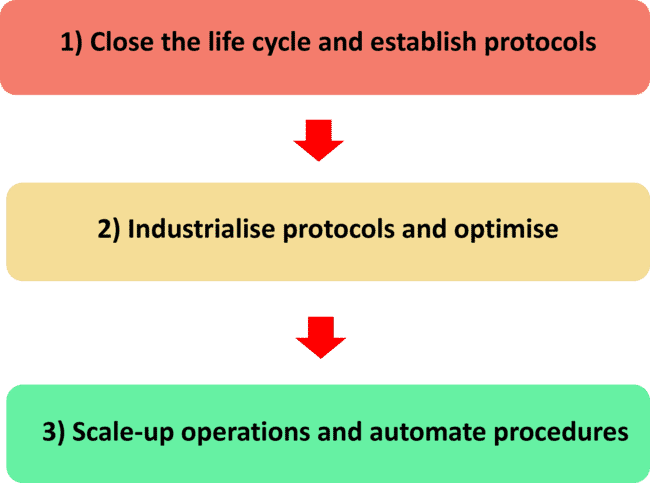

Regardless of method, a healthy seaweed industry requires a reliable supply of high-quality seedlings at a reasonable cost. After all, if seeding costs can be reduced significantly from their current levels, while also giving higher and more predictable yields, this is a big step towards farmers achieving profitability. I propose that achieving the above goal is a three-step process, loosely based on the well-known technology readiness level (TRL) scale. Let’s look at each stage in detail.

Close the life cycle and establish hatchery protocols

Before cultivating at any kind of scale, it is important to understand the entire life cycle of the species to be grown, so that each stage can be controlled and optimised: inducing fertility, releasing seeds, reproduction, development and growth. These methods need to be developed for each species individually as seaweed life cycles vary enormously.

In the West, we have had control over the life cycle of a handful of kelp species for some time now, and it helps that they possess a relatively simple biology that is easy to manipulate. Kelp become fertile under winter conditions (real or artificial) and produce sori which contain spores (seeds). The spores, released following gentle desiccation of the sori, can be used for seeding. Another option though is to use the spores to produce vegetative gametophyte cultures which are usually kept this way through specific light and nutrient conditions. These can be kept alive and growing (propagating) for many years, doubling in biomass every few weeks, and then fertilised when needed to produce juvenile seedlings (sporophytes). This form of seedling production puts less pressure on natural kelp populations, as large quantities can be produced from a small quantity of wild kelp. It also gives greater control over both quantity and timing of seedling development, compared to using spores.

What is exciting is that we are starting to see protocols being developed for species with more complicated life cycles, and this is primarily driven by market demand due to their favourable taste and nutritional content. Nordic Seafarm in Sweden has been successfully growing sea lettuce (Ulva sp.) at sea for several years now. Hortimare in the Netherlands and OceanWide Seaweed in Denmark have also had early success with producing dulse (Palmaria palmata) at sea, although so far only at a relatively small R&D scale. Hatchery protocols for Asparagopsis cultivation are also in development, with Greener Grazing a key player. This is driven by the large demand, not for food, but for its methane-reducing properties when used as cattle feed.

Industrialise protocols and optimise

Once the key life cycle stages are under control it is time to optimise the protocols, taking them from the lab to industrial scales. It is one thing being able to release some spores in a flask and seed a few meters of rope, and quite another thing to seed several kilometres. To use a famous quote from business, you need to “nail it, then scale it". The same principle applies to the whole seaweed value-chain. It may seem obvious, yet there are several examples of companies who have used the exact opposite strategy.

Improving each step of production

To cultivate at a commercial scale, it is important to maximise the efficiency of each step and eliminate waste. This involves spending a lot of time testing ways to optimise steps such as fertility induction, spore releases, vegetative seed production (not possible in all species), fertilisation of seeds, the retention of seeds/seedlings on the substrate, growth rates in the nursery, reducing contamination and so on. These are the things that very few people will see, understand or even appreciate, but sweating the small stuff and searching for marginal gains will have disproportional impacts on the overall success later. It is this stage of optimisation that is the most species-specific, and knowledge from one species is unlikely to transfer easily to another.

© SINTEF Ocean

Reducing waste and saving space

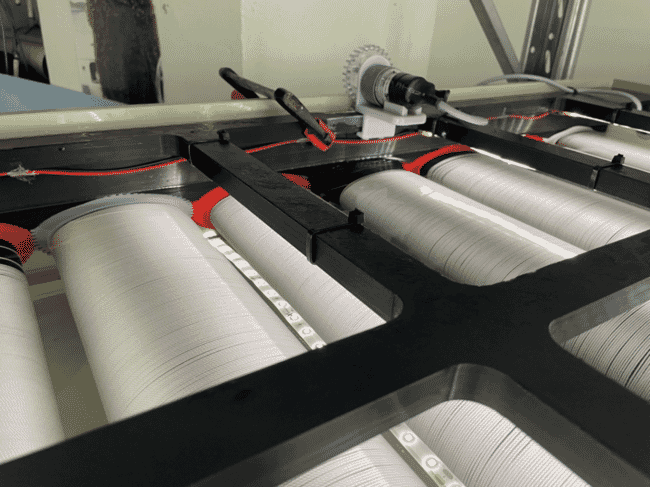

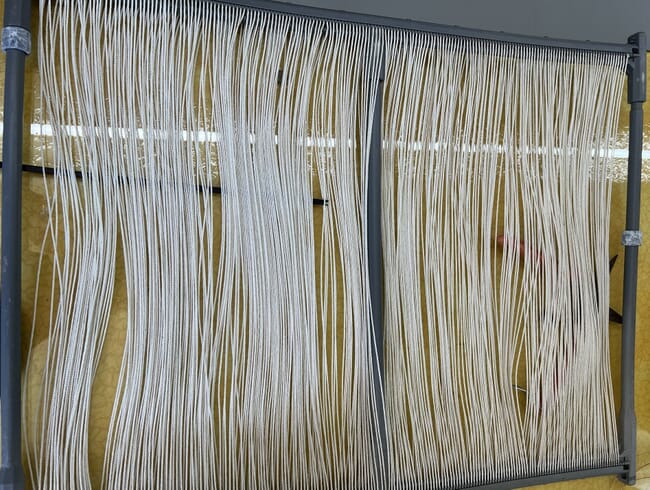

Another important element to optimise is the use of space, energy and seawater. This is especially true for nursery incubation, which requires specialised cultivation rigs (lights, shelves, tanks, pipes, seawater supply). The good thing is that nursery design optimisation is fairly independent of the species being cultivated, although the specific nursery conditions used may vary (eg light, water temperature, water flow etc.). The most efficient incubation systems currently involve placing upright spools of thin twine in boxes with water flow-through and light from above. The Norwegian Seaweed Centre, hosted by SINTEF Ocean, has been developing systems to incubate spools (cultivation rope wrapped around pipe) even more space efficiently in drawers, while also rotating them to ensure consistent light exposure. The act of moving the spools creates water movement, which has the added advantage of improving growth.

We can also look to Asia for inspiration, as their nurseries produce seeded twine at orders of magnitude greater than here in the West. I have heard stories of facilities that can produce over 1 million kilometres of twine with only a handful of people. When it comes to space, they use large raceways filled with seed collector frames (not spools). These can be closely packed, like honey frames within a beehive enclosure – just leaving a gap for light to reach the seedlings. It is a bit of a puzzle why the West has not adopted this system of frames, opting for spools instead. Ignorance is likely a factor. However, inertia could be another explanation: now that most companies are accustomed to spools, and technologies have developed around them, it is perhaps a question of the cost and effort of changing to new ways of doing things.

© Seaweed Insights

Improving yield

The final role of a hatchery is to optimise yields at sea. Almost every stage in the hatchery has the potential to influence yield, not just the characteristics of the seedlings when deployed (including size and density). This is also the hardest part to optimise, because designing and following trials properly from hatchery to sea is both expensive and time consuming, requiring highly trained scientific expertise. Another challenge is the seasonal nature of seaweed production, meaning there is only one shot each year to test things. Despite having over a decade of experience farming kelp in the West, there is still likely a lot to learn about how hatchery conditions can improve yields. Much focus in the hatchery has been on improving nursery growth, whereas in the future I think we will also see the hatchery as an opportunity to acclimate seedlings to their life at sea, which will result in greater yields.

One hatchery innovation that helped revolutionise the Asian industry, which has not been copied much by the West, is the widespread production of summer seedlings. Essentially, they grow the seedlings to a large size (5-20 cm) over the summer before deploying them at sea in autumn by splicing or transplanting either the seeded twine or the seaweed itself into the cultivation rope. Not only do the seedlings get a major head-start in terms of size, but there is also reduced competition for space between juvenile seaweeds at sea.

It is interesting that many Western companies, such as Arctic Seaweed and Hortimare, are essentially moving in the opposite direction: deploying microscopic sporophytes via direct seeding. However, some companies are starting to take inspiration from the Asian techniques here in Europe. Ocean Forest in Norway have publicly stated that they deployed seedlings of approximately 10 cm in the autumn of 2024 (albeit with the conventional twine wrapping method), citing improved yields as the reason. One company in the north of Norway (Polaralge) has also started experimenting with transplanting large sporophytes directly into the carrying rope and have been achieving impressive yields in their trials. This splicing technique is highly promising but needs to be automated - it already has been by some farmers in South Korea, who have developed machines capable of cutting and inserting small pieces of seeded twine into the cultivation rope.

© Polaralge

When it comes to improving yield, breeding can also play a role. Asian farmers have been selectively breeding kelp for over 50 years. Europe and North America are playing catch-up, and have started researching using breeding to optimise yield, nutritional composition and the content of valuable compounds, while also making strains more tolerant to environmental stressors such as increased temperatures. However, selective breeding is – by definition – a gradual process; it also requires a lot of resources and expertise. Modern techniques can help speed this up.

In the future, CRISPR gene editing may be applied to seaweed and allow for the targeted editing, deletion or insertion of specific genes. This technique has been successfully demonstrated on gametophytes of S. japonica by researchers in Japan but otherwise remains in its infancy. There would likely be regulatory problems (especially in Europe) from commercialising the sale of crops arising from gene editing, in a similar way to other genetically modified organisms in agriculture. That is why most research is currently focused on “natural” methods for selecting favourable strains. In the USA, Scott Lindell’s group at WHOI has pioneered using gene sequencing, followed by statistical tools for predicting which breeding pairs will produce the best offspring of sugar kelp. In Europe, the EU-funded Blue Bio Boost project, led by Åshild Ergon at NMBU in Norway, aims to develop sustainable breeding methods to improve the efficiency of selection for suitable genotypes of both sugar kelp and sea lettuce. There is also a general interest in methods to create infertile sporophytes that cannot mix with local seaweed populations.

Scale-up and automate the most labour-intensive steps

Once commercial scale protocols have become standardised, with most of the inefficiencies ironed out, seedling production can be scaled up and then automated. This reduces operating costs through economies of scale and reduced labour. It is important to realise that optimisation will always be an ongoing process, but it should just be tinkering or fine-tuning at this point.

The Western kelp industry is arguably in the early part of scaling up, although this has stalled due to a drop in market demand over the last few years. The issue is that scaling up hatcheries requires large investments into infrastructure. This only makes sense if there is a strong and predictable market pull for seaweed biomass at the end of the value chain, creating demand for seeds. Without this certainty companies are unwilling to make these investments. This can quickly change if the market turns.

Automation is similarly expensive in terms of initial investments and is also affected by uncertain market conditions. For an example of how automation can reduce labour costs in hatcheries we can look at the process of producing gametophytes. This is still a largely a labour-intensive process where cultures are grown in flask and require time-consuming maintenance every few weeks to keep them growing: changing of culture media, physical grinding of the gametophytes to reduce their “clumpiness”, and checking for contamination.

The next major development is likely the adoption of bioreactors to further automate the production of these gametophytes while improving biosecurity and reduce contamination risk – bioreactors are specialised chambers where you can control many of the growth conditions: temperature, pH, mixing/grinding, light intensity and wavelength, in addition to nutrient media exchange. Industrial Plankton in Canada is producing these commercially, and seedling suppliers such as Seaweed Solutions (Norway) and research institutes such as Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI, USA) are already adopting them. They are not cheap though, with a set of four 2 litre bioreactors costing around $50,000. The per litre price is likely to come down though as they develop bioreactors of larger volume.

© Industrial Plankton

For the nursery stage, the industry still lacks efficient solutions for automating several key stages, including spool production, seeding, and monitoring and control of both nursery conditions and seaweed growth. These things should all be possible with a combination of robotics and computer vision. The nursery of the future could be more or less self-operating: with seeds and spools being the input and seeded line the output a month or so later. Once this automated nursery technology is mature, and without the need for highly trained people, it opens the possibility for smaller decentralised nurseries, perhaps similar in concept to the simple open-source shipping container nursery designs being developed between Greenwave and Hortimare in the USA. One advantage here would be that nursery incubation could be carried out close to the farms, maybe even by the farmers themselves (either alone or in cooperation with other farmers). While a centralised hatchery model may have advantages in terms of economies of scale and consistent quality control, a decentralised model can provide resilience (no single point of failure) and agility when it comes to responding to farmers logistical preferences around deployment timing.

Final thoughts

In this article I have proposed three key stages to scaling up seaweed hatcheries. This is slightly simplified and also not a perfectly linear process. However, it does help us visualise where the industry is and where it needs to go. It also allows us to see how close different seaweed species are to reaching commercial scale, and which steps they must take to get there. In the West, kelp is essentially ready for the scale-up and automation phase, but reliable and predictable market demand is needed to give investors the confidence to invest in the infrastructure that is required. In some of the other commercial species (eg. Ulva, Palmaria, Asparagopsis), where there is stronger market demand, the protocols are not mature enough to deliver the scale needed due to the complexity of the life cycles and the optimisation challenges that this presents. In both cases, these obstacles are possible to overcome with the correct allocation of resources.

It should not fall on the industry alone to solve all these bottlenecks, and there needs to be financial support for research to work on problems across the value chain. If hatchery truly is destiny in seaweed farming, then we should be cautiously optimistic about the future of the industry. With many smart people focused on solving some of the key hatchery bottlenecks, and increased collaboration to help address other parts of the value chain and the larger industry problem of market demand, I think there is a bright and exciting future ahead for cultivated seaweed.