The vaccine has proved effective in reducing tilapia mortalities in other regions, including West Africa © Virbac

Produced by Virbac, the vaccines are designed to counter a particular strain of Streptococcus agalactiae, called serotype 1A, that has been sweeping the country in the last few months.

The outbreak has been classed as a national sanitary emergency by the Colombian government, putting at risk an industry that – according to Rabobank – produces in the region of 140,000 tonnes of tilapia a year.

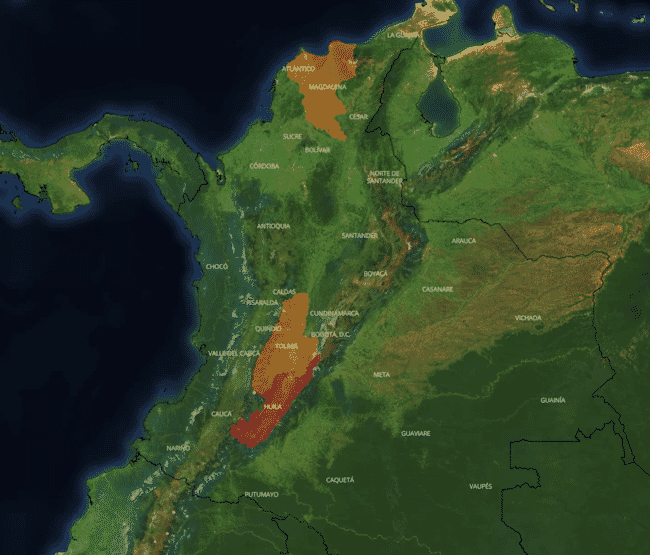

According to Mario Aguirre, Virbac’s technical consultant for warm water species in Latin America, the outbreak has hit the region of Colombia – Huila – that’s responsible for 68 percent of the country’s tilapia production, with particular severity. Since then, it has spread to farms in both the Atlantic and Huila Departments.

The Animal Health authorities (ICA) have declared mortality rates in the following departments: Tolima (10 percent), Huila (12 percent), Magdalena (37 percent), and Atlántico (47 percent), but some commentators have suggested that it might be higher, based on some of the reports from individual farms, as well as data collected from outbreaks of the variant in other parts of the world.

According to Aguirre, one of the country’s key production areas is Betania Dam, which has experienced rapid fluctuations in water levels. This has led to rapidly changing water quality factors, thereby ramping up stress in the fish and making them more vulnerable to pathogens.

“It’s a chronic disease problem, and the government has opened the door for vaccine producers by calling a national sanitary emergency. It’s the first time in the region that a government has made this decision – because Colombia exports a significant amount of its tilapia to the US, so it is important for the country’s economy and is also an important part of food security in Colombia and many people are likely to lose their jobs,” he says.

A novel strain requires a novel solution

Given that serotype 1A is novel in Colombia, the government has authorised the import of 400,000 doses of an experimental vaccine that Virbac has developed for the variant – which had previously been more common in Asian and African tilapia farms. The authorities have also made it mandatory for farmers to follow certain biosecurity protocols and report any unusual levels of mortalities.

Until a year ago, the only vaccines available in Colombia were monovalent vaccines containing S. agalactiae serotype 1B, according to Luis Velasquez, manager of Virbac’s warm water species business unit in Latin America. However, while Virbac vaccine offers hope of getting over the worst of the outbreak, Velasquez stresses that farmers need to be aware that it’s only one element in a whole range of measures – including biosecurity, disinfection, production strategies, genetics, among others – required to ensure the long-term health of the country’s tilapia sector.

The vaccine that’s being deployed by Virbac contains both the1A and 1B serotypes, and has been deployed in countries such as Ghana, where it was used with great effect by Tropo Farms, the country’s largest tilapia producer, according to Adrian Astier, key account manager for the African and Mediterranean region at Virbac.

According to Astier, unvaccinated tilapia that are exposed to serotype 1A, especially for the first time, can experience up to 40-60 percent mortality rates.

“The performance of the vaccine tends to be better in the warmer seasons because this is when Streptococcus outbreaks usually happen,” he adds.

However, Aguirre stresses that this rate will vary.

“We are very optimistic that this vaccine will be effective in Colombia when we test it, but we can’t assure a specific percentage of survival because it will vary depending on a range of conditions on each farm,” he explains.

“A vaccine is a tool in your fish health kit; you have to use it but also make sure you follow best aquaculture practices – to keep the fish as healthy as possible,” Astier adds.

“In terms of cost-effectiveness, we recommend giving intraperitoneal (IP) injections when the fish reach about 25 grams because they are only affected at a later stage in the production cycle, and this will protect them until harvest,” says Astier.

Global implications

Looking at the bigger picture, Astier warns that with the increased movement of tilapia around the world, the spread of diseases is only likely to ramp up, and – equally – there will be a need for increasingly complex vaccines.

“Once the pathogen is in a lake, for example, it is very difficult to eradicate it. It’s not like in the poultry sector, where you can just disinfect the warehouse. Once it’s in the country, it remains, unfortunately,” he says.

According to Aguirre, while it was previously only those farmers growing tilapia for export to the US who vaccinated their fish due to guaranteed good survival and meet with the market demand, now farmers from across the spectrum, including small-scale producers who sell their fish domestically, are looking to use vaccines.

However, he stresses that farmers must understand that it’s not a panacea.

“The vaccine doesn’t make miracles – the fish must be in good condition, and you have to apply it correctly… everything must be in place to guarantee that the vaccine is effective. It’s a big challenge for everyone – from the suppliers to the farmers,” he says.

While it’s clearly an alarming time for Colombia’s tilapia farmers, one potential silver lining is that – in the long term – if farmers start to follow best practices, it could mark a seismic shift in the sector.

“I think it’s a bit like the outbreak of the ISA virus in Chile [in the late 2000s] – which led to important changes in the structure and management of the salmon industry in Chile,” Velasquez suggests.

In the meantime, farmers will be awaiting the results of the vaccine and hoping that they are able to harvest any unvaccinated fish before their farms are hit by the pathogen.