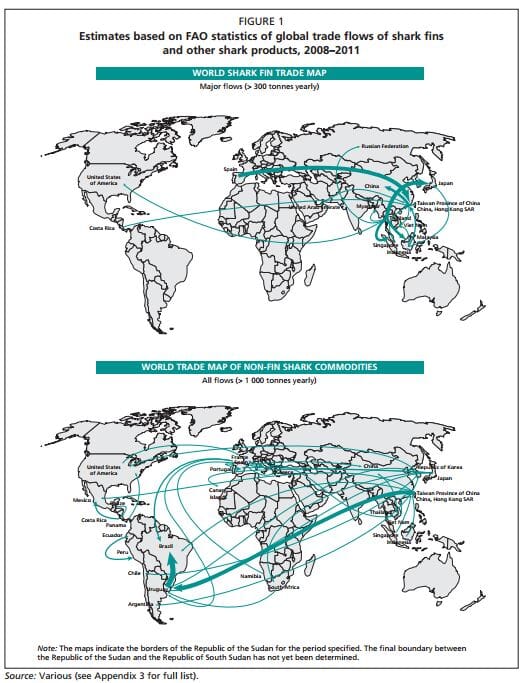

People have caught and consumed sharks for many hundreds of years, but only in recent decades have strengthening demand and the various forces of economic globalisation combined to create a truly global market (Figure 1).

Today, industrial and artisanal fleets from all over the world supply traditional Asian markets for shark fins (this includes skate and ray fins), while the meat of the same captured sharks is increasingly being diverted along separate supply channels to meet demand in growing markets such as Brazil.

This lengthening of supply chains means that shark products will pass through multiple countries as they move along regional trading routes or undergo various processing stages before consumption.

Meanwhile, a combination of demand growth and anti-finning regulations intended to encourage the full utilisation of carcasses has seen the market for shark meat expand considerably.

In turn, this has led to fishers seeing sharks increasingly as commercial species to be actively targeted, rather than by-catch species landed unintentionally while targeting more valuable species such as tuna or swordfish.

The net effect of all these developments has been to increase fishing pressure on many shark populations, including those whose geographical distance from the end consumer had previously kept them relatively untouched.

It has also greatly complicated the task of ensuring that the economic incentives driving the now-global industry do not result in the continued unsustainable utilisation of shark resources.

It is in this latter capacity that international bodies such as FAO can play an important role. Official FAO statistics (FAO, 2011–2014) conservatively put the average declared value of total world shark fin imports at $377.9 million per year from 2000 to 2011, with an average annual volume imported of 16,815 tonnes.

In 2011, the last year for which full global data are available, the total declared value of world exports was $438.6 million for 17 154 tonnes imported. The corresponding 2000–2011 annual average figures for shark meat were 107 145 tonnes imported, worth $239.9 million; while in 2011 only, the reported figures for total world imports of shark meat were $379.8 million and 121,641 tonnes for value and volume, respectively.

The significant difference between the unit value of trade in both commodity categories reflects the much higher value of shark fins, which retail as some of the most expensive seafood items in the world.

Historically, this discrepancy has sometimes seen fishers adopt the controversial policy of removing fins from the captured shark before discarding the less valuable remainder, alive or dead, in order to maximise the value of the contents of their limited hold space.

However, the emergence of new markets for shark meat, together with stricter regulatory requirements, has at the same time created greater incentives for full utilisation of shark carcasses and exposed the resource to a new source of demand that may increase, or at least maintain, its vulnerability to overexploitation even if demand for shark fins weakens in the long term.

This is an important point to consider, as it implies that even where anti-finning campaigns from environmental groups are successful in terms of decreasing consumption of shark fins.

State of the global market for shark products and/or reducing the prevalence of the practice among fishers of shark, the pressing need to maintain and develop monitoring and regulatory systems remains.

At the international level, the markets for meat and fins are largely distinct from each other; the world’s major shark producers generally export both commodity types, but there is much less overlap between importers.

However, the widespread practice of recording trade in shark fins within aggregated commodity categories together with shark meat presents obvious difficulties to any attempt to analyse the two markets separately.

Even where customs authorities do maintain separate categories for meat and fins, there are often other issues with data quality and reliability that may result in a distorted or obscured picture of the real situation and inhibit meaningful analysis.

The quantitative summary of the world market for shark products that constitutes the bulk of this publication must thus be considered in conjunction with an evaluation of the trade recording practices of the world’s most important producers, traders and consumers of shark products, particularly in the case of shark fins.

Shark fins

The vast majority of shark fins are destined for consumption in a relatively small selection of countries and territories in East and Southeast Asia such as China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia and Viet Nam.

However, the world’s largest consumers of shark meat are found in South America and Europe, with the most important importers being Italy, Brazil, Uruguay, Spain and the South Korea – the latter being the major importer of skate and ray meat.

In the case of fins in particular, the term “exporters” covers both primary producers such as Indonesia and Spain, whose vessels actually catch the sharks, and re-exporters, a role that may be further divided into pure traders, such as the United Arab Emirates, and processing traders such as China.

This classification is helpful but not perfect, however, and most countries are involved, if only to a minor extent, in all three activities.

As well as being one of the largest consumer markets for shark fins, Hong Kong has historically been the most important trader of shark fins in the world, accounting for the majority of recorded imports and value since data first became available, and also establishing itself as the world’s largest exporter from the late 1980s onwards.

Hong Kong is also notable for being the only customs territory that that has historically distinguished between four different types of shark fin in its trade database, maintaining separate commodity codes for frozen, dried, processed and unprocessed shark fins.

Hong Kong is not a producer, and essentially the entirety of its outgoing trade consists of shark fins that have been imported from shark-catching countries or regional traders and then re-exported.

Singapore’s role in the world market for shark fins is similar, while China and Taiwan produce significant volumes of shark domestically in addition to consuming, importing, processing and trading fins (as exports and re-exports).

The world’s major shark fin exporting producers are Spain, Indonesia, Taiwan and Japan, although the aforementioned issues with data quality and reliability that characterise shark fin trade and shark capture statistics make it difficult to quantify accurately the relative importance of each individual producing country.

In particular, it is difficult to describe in any detail the role of countries such as Costa Rica, which appear to not only produce shark fins domestically but also act as important trading hubs for neighbouring countries and other foreign fleets fishing in the surrounding waters.

Shark meat

While global trade in shark fins appears to have decreased slightly since the early 2000s, global trade data show the trade in shark meat expanding steadily over the last decade or so, and the latest FAO official figure of 121 641 tonnes ($379.8 million) of chondrichthyan meat imported in 2011 represents an increase of 42 per cent by volume compared with 2000.

This growth is probably driven in large part by the need to supply increasing global demand for seafood when the potential for increased production from alternative wild marine fish stocks is extremely limited.

Another reason behind this growth may well be the widespread implementation of finning regulations that require that shark carcasses be landed together with their fins – often employing a 5 per cent fin-to-carcass weight ratio – thus potentially prompting the development of markets on which the meat can be sold.

However, it is important to recognise that the trend of rising unit values for traded shark meat across many key trading countries, even as global supply volumes increase, also points to strong and growing underlying consumer demand.

Large producers such as Spain and Taiwan, in addition to their roles as suppliers to the shark fin markets, now also export large volumes of shark meat to their respective major markets of Italy and Brazil.

Uruguay has also emerged as an important re-exporter of processed shark meat, supplying the rapidly expanding 4 State of the global market for shark products Brazilian market.

European and North American markets such as the United States of America, Italy and France seem to have a preference for dogfish species, although this is possibly influenced by sanitary regulations that prevent the import of larger shark species owing to high mercury content.

Demand in South and Central American and Asian markets, in contrast, appears to be mainly for larger species. The Republic of Korea is notable for importing relatively small quantities of true shark meat but accounting for the vast majority of world imports of skate and ray meat.

In general, markets for shark meat are much more diverse and geographically dispersed than those for shark fins, and as a result there is considerable potential for expansion.

Information gaps and data paucity

Relatively little is known about the increasingly globalised market for shark-derived products.

Usable data on utilisation and trade are still restricted to the two most-traded products, shark meat and shark fins. Other products such as shark liver oil and shark skin are also traded, but these quantities are minimal by comparison and, consequently, the available data are extremely limited.

Even in the case of meat and fins – as this publication demonstrates – the available data cover only a proportion of what is actually caught and traded.

Capture statistics, although improving, are often aggregated, i.e. do not distinguish between species, while the majority of existing trade records do not allow consistent identification of product forms or reliable tracking of values or volumes traded over time.

In addition, the species of shark being traded is only rarely identified in trade records for shark meat and never for shark fins.

Knowledge of the specific characteristics of domestic markets is also very limited, and there is little concrete information on such things as the types of products being marketed, the prices of these products at different points in the supply chain, the profile of the typical consumer, and the major demand drivers.

This information is crucially important for those concerned with the environmental effects of the exertion of market forces on shark populations, as well as for those who are directly involved in economic activities within the industry and who are thereby dependent on the continued existence and relative abundance of sharks for their well-being.

This technical report thus attempted to do three things. First, it seeks to address, as much as the data allow, the gaps in the knowledge of the crucial features of the world market for shark products and to identify the key features and trends that characterise this market.

Second, it attempts to illuminate the gaps that remain as a result of data paucity. Finally, in light of these findings, it offers a range of recommendations for policy and other action to be taken at the national and international levels to attempt to achieve the sustainable utilisation of chondrichthyan populations.

September 2015