© Peter Tubaas

Researchers have found that infective larvae from some sea lice families spend more time in deep water than others. Their new study, published in the International Journal for Parasitology, suggests that lice could adapt to lice skirts and snorkel cages used on some salmon farms by swimming deeper.

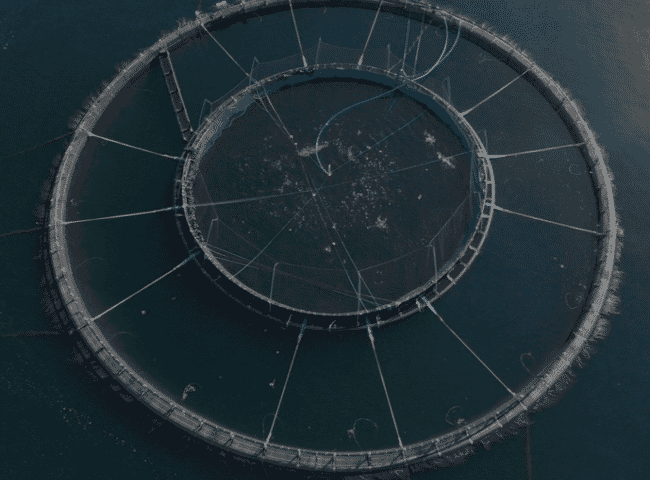

Salmon lice have evolved resistance to most of the drugs used on farms, meaning alternative strategies for louse management are needed. One approach is to use skirt and snorkel barriers that prevent copepodids – the infective larval stage of lice – from getting into cages in the first place. But whilst these cages block most copepodids, those swimming deeper in the water can sneak underneath these barriers.

Researchers from Norway’s Institute of Marine Research and the University of Melbourne tested the swimming depth preferences of copepodids. Thirty-seven different families of lice were reared and their swimming behaviour observed using 80 cm-tall columns of water. These columns were pressurised to simulate the different pressures experienced at 0, 5 and 10 metres depth. Twice as many copepodids swam to the top of columns at higher pressures.

“Our study provides strong evidence that lice adjust their behaviour using pressure cues,” said lead author Andrew Coates from the University of Melbourne. “When lice sink below 5 m, they can sense the pressure change and increase their swimming rate to get back to the surface.”

But this behaviour wasn’t the same for all families of lice. Lice from some families were much less likely to ascend to the surface, even under pressure equivalent to 10 m deep. In some of the families tested, 80 percent of siblings swam to the top, while in others, less than 20 percent did.

“Some families seemed happy to stay deeper, at a simulated 10 metres depth. These might have a better chance of sneaking underneath skirts and snorkels to infest fish.” The similarities within families suggests that this behaviour might be heritable.

During the early days of drug treatments on farms, a small portion of lice had genes that improved their survival to treatments. These genes were then passed on to offspring. These two factors allowed lice to evolve widespread drug resistance. Similarly, a small number of lice successfully infest skirt and snorkel cages. The authors note that evolution could occur if (1) these successful lice have deeper-swimming behaviours and (2) these behaviours are hereditary. Such evolution would mean skirts and snorkels would become less effective over time, and farms would have to rely on other strategies.

“Further research is needed to see whether the family variation observed in the lab translates to the natural environment. Nevertheless, the results highlight the need to think about whether lice can adapt to depth-based louse management strategies” said co-author Frode Oppedal, from the Institute of Marine Research. “Parasites are incredibly adaptable organisms and we need to consider evolutionary processes as we implement new disease control strategies.”

Further information

The full study can be accessed at Parasites under pressure: salmon lice have the capacity to adapt to depth-based preventions in aquaculture