Although the idea of keeping cod alive, for a month or more after capture, might seem peculiar, or a development that must be linked to the rise of the commercial aquaculture industry of the species in the late 1980s, it’s a practice that’s been going on for at least a century longer.

“The Norwegian fleet has been taking part in the live capture and storage of cod at least since the 1880s,” explains Geir Sogn-Grundvåg, who is leading Nofima’s CATCH project, a four-year research project into the live capture of cod, which has been financed by the Research Council of Norway.

“At that time some vessels, which were sailing ships, would travel to Iceland to fish. The bulk of the catch would be salted, but during the last few weeks of the voyage some would keep their catches alive so they were still fresh by the time they arrived in Grimsby, where they could be freshly slaughtered and therefore attract a premium price,” he observes.

© Geir Sogn-Grundvåg, Nofima.

While fisheries technology may have changed considerably in the ensuing century, the market forces behind the concept are much the same.

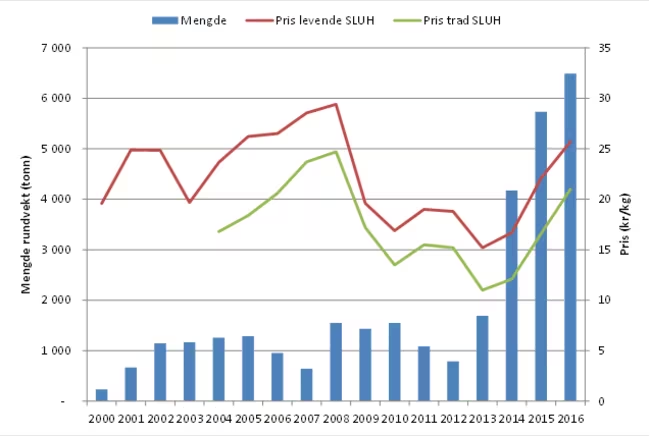

“We saw a resurgence in live storage of cod, as well as the birth of the commercial cod aquaculture industry, in the late 80s and early 90s at a time when the Norwegian cod quota fell dramatically, and prices for the fish started to rise,” explains Geir. “The quantity stored live has varied considerably, and is closely related to the total quota of cod – the attractiveness of the concept is generally higher when quotas are low.”

Keeping the cod alive during the transfer from the seine nets into the holding tanks on the vessels requires skill and experience, but survival rates under the right skippers are now quite high.

“In the right conditions, good skippers can keep up to 90% of their catches alive,” says Geir. “It depends on a number of factors – the speed the net is retrieved needs to be kept slow, but in bad weather the speed of transfer from the net can be slowed down too much and the fish can be damaged while crowded in the nets near the surface as they’re awaiting transfer to the boat.”

Once onboard there has been an element of trial and error required in how best to keep the cod in good condition – both in the holds of the fishing vessels themselves and in the marine cages where they are then transferred to prior to harvesting.

© Nofima

“Cod rupture their swim bladders when they’re brought up to the vessel from the nets. This causes them to crowd on the bottom of the holds or cages for around 12-24 hours before their swim bladders heal and they can regain control of their buoyancy,” Geir continues. “As a result, if they are placed in a standard salmon cage [which has a v-shaped bottom] they can overcrowd to such an extent that they will suffocate. This means that stiff, flat-bottomed cages are needed, while the holds in the vessels are now equipped with flat-bottomed tanks which have water upwelling through them from underneath.”

Finally, there’s the challenge of looking after the cod once they’ve been transferred to marine pens prior to harvest.

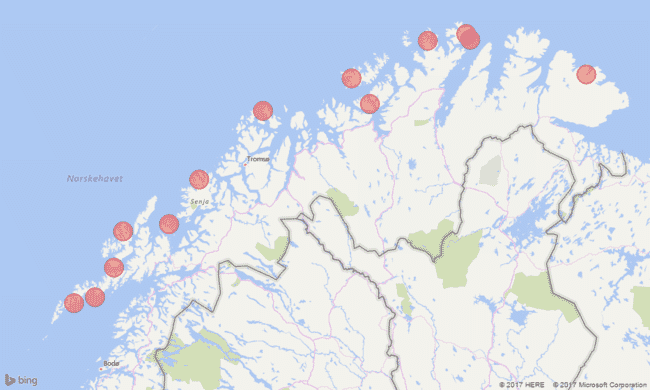

“There are currently around 15 sites along the coast with pens for the cod to be stored prior to harvest,” explains fellow researcher Øystein Hermansen, “but few of the operatives have aquaculture experience – they need to learn how to handle the fish, as they can be stored in the pens for several months, so it’s quite a steep learning curve. Thankfully there have been very few health issues in these sites, with no treatments, that I’m aware of, required in the last decade or so.”

© Geir Sogn-Grundvåg, Nofima.

Equally, the cod consume little feed prior to harvest.

“Following their experience of capture,” says Øystein, “the cod tend to eat very little in the first 2-4 weeks in the pens. They start to feed after a month or so, at which point it’s mandatory to provide them with a basic maintenance ration, but not many producers attempt to fatten them up in these sites.”

Despite the extra work generated by the live-storage requirements of the fish, a number of skippers have been attracted to the sector – in part due to the premium that can be raised by live-stored cod.

“As live cod take up more room than dead fish, and it takes longer to haul in the nets, catching capacity of vessels is reduced by about 50%,” explains Øystein. “As a result, just like in the days of shipping live cod to Grimsby, a price premium is needed to make it worth the skippers’ while and the fact that these cod can be kept alive until outside the main Skrei season (which runs from January to the end of April) then fetch a premium when sold fresh in the off-season in key markets such as France, Be-Ne-Lux and Spain.”

The CATCH team is currently looking at whether off-season sales to these markets could be developed further, and they observe that the live-stored cod have more advantages than purely being available off-season.

“Live-stored cod is also excellent quality for fresh fish counters – the industrial slaughtering process used at harvest means a high proportion is ‘superior’ quality, especially compared to other catch methods such as gill netting,” Geir reflects.

Despite this they have encountered a number of obstacles.

“We’re looking across the whole value chain and are currently investigating the potential. Our initial observations are that the Spanish market looks promising, but some retailers have an emphasis on seasonality, in part so that they can buy in one species at a time – in high volumes for good prices,” says Øystein.

Such a situation is not helped by the comparatively small volumes of live-stored cod available on the market, with annual landings creeping up slowly from several hundred tonnes a year since the turn of the century to reach a high of 6,600 tonnes last year – an impressive growth rate but a drop in the ocean when compared to Norway’s national cod quota, which currently stands at 400,000 tonnes.

However, the Nofima researchers see scope for the sector to continue to grow – a trend that has been particularly apparent since 2012 – not least thanks to government incentives.

“In 2013 a quota incentive for the live-capture of cod was introduced,” explains Øystein, “which means that each tonne of live-stored cod counts for only 50% of quota of its conventionally harvested equivalent. This effectively means that the skippers can almost double their landings.

As a result, despite a recent decline in the number of vessels taking part in the fishery, landings look set to continue to rise.

“We’re not quite sure why the number of vessels declined from 25 to 17 this year,” says Øystein, “but several operators are now in the process of building new ones, as they seek to capitalise on the quota incentive. However, how long the incentive will last remains to be seen – conventional cod fishermen are not too happy with a part of the quota being allocated to live storage, so there is pressure on the government to revoke the incentive.”

However, the Nofima researchers see scope for the sector to continue to grow – a trend that it has experienced since 2013 – not least thanks to government incentives.

“In 2013 a quota incentive for the live-capture of cod was introduced,” explains Øystein, “which means that each tonne of live-stored cod counts for only 50% of quota of its conventionally harvested equivalent. This effectively means that the skippers can almost double their landings.

As a result, despite a recent decline in the number of vessels taking part in the fishery, landings look set to continue to rise.

“We’re not quite sure why the number of vessels declined from 25 to 17 this year,” says Øystein, “but several operators are now in the process of building new ones, as they seek to capitalise on the quota incentive. However, how long the incentive will last remains to be seen – conventional cod fishermen are not too happy with a part of the quota being allocated to live storage, so there is pressure on the government to revoke the incentive.”