Click on the image to enlarge © Osmundsen et al, 2020

A recent study published in the journal Global Environmental Change has reviewed the metrics and methodology of eight global sustainability certification schemes for aquaculture: ASC, GLOBAL GAP, Global Aquaculture Alliance (GAA), BRC Global Standards, International Featured Standards (IFS), Scottish Salmon Producers’ Organisation (SSPO), Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), and Friend of the Sea (FOS).

Their analysis shows that the schemes have a relatively narrow definition of sustainability – tending to prioritise environmental indicators at the expense of other benchmarks.

Though the emphasis on environmental factors could make the aquaculture industry greener, the narrow focus risks skewing the industry and public definition of sustainability, making it less workable long-term. The researchers stress that sustainability is multi-dimensional. Unless independent certification schemes can apply the full definition of sustainability to their audits, the aquaculture industry won’t make any progress in achieving its sustainability goals.

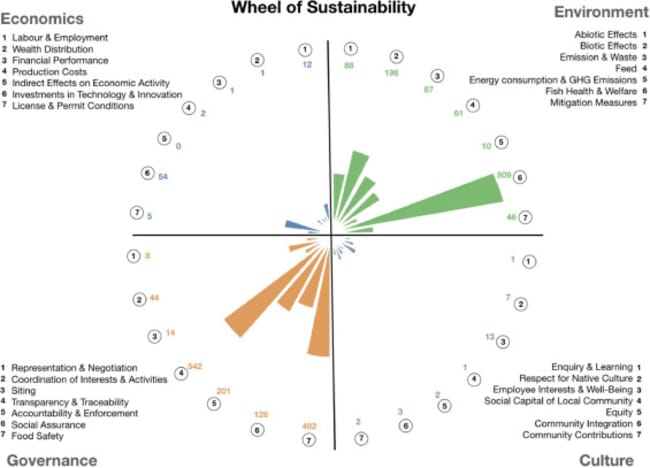

The researchers suggest embracing the “wheel of sustainability” model when creating certification schemes. This concept moves beyond the triple-bottom-line or three E’s and defines four elements of sustainability: economics, environment, governance and culture. By adopting this model, the schemes could provide practical and concrete ways for aquaculture firms to achieve sustainability benchmarks. It also gives consumers more accurate information on sustainable production, justifying the premium they pay for sustainably-produced seafood.

Why aquaculture sustainability certifications matter

Aquaculture still faces sustainability challenges. Issues like environmental degradation, fish escapes and the long-term viability of fishmeal in aquafeeds have been recurring criticisms of seafood production.

The wider public is tuned in to the industry’s pitfalls, looking to eco-labels and independent sustainability certifications to ensure their seafood purchases don’t compound the sector’s ills. Though these labels are advantageous from a marketing standpoint and encourage companies to meet sustainability targets, advocates worry that the schemes may be limited. Previous analysis suggests that they have a narrow focus – over-representing large production sites while overlooking smaller fish farmers.

The other criticism stems from what the schemes purport to measure and how this feeds back to the industry and wider public. In many cases, the working definition of “sustainability” for aquaculture is being established by these schemes, not by researchers or other experts. The certifications are also beginning to define the public’s understanding of sustainability. This perpetuates the limitations or flaws in the schemes and leaves the overall definition of sustainability unclear.

The current analysis

The research team adopted the “wheel of sustainability” model as a working definition of sustainability. That model identifies four key characteristics of sustainable aquaculture production: economics, environment, governance and culture.

The “economics” category focuses on the commercial impact that the aquaculture company has on the surrounding community, beyond profitability. “Environment” emphasises limiting the human impact on nature, prioritising fish health and welfare and mitigating the negative impacts of production. “Governance” covers how the industry is regulated, food and worker safety, the extent to which production is transparent and traceable and industry norms. The “cultural” domain covers the role of the aquaculture organisation in their community’s social fabric. The researchers looked at how organisations respect the surrounding culture where they operate and employee well-being indicators. The idea is that each of the four element reinforces the other, creating a holistic picture of sustainability.

After identifying the model, the researchers reviewed the indicators of eight of the most widely used certification schemes in aquaculture. The team then broke the 1,916 indicators into the four domains of the wheel of sustainability.

The researchers found that the eight schemes predominantly focused on the environmental and governance portions of the wheel, representing 46 percent and 50 percent of the indicators, respectively. Cultural and economic indicators didn’t get as much coverage, only 1 percent of indicators across the eight schemes focused on culture and 3 percent focused on economics.

On one level, the schemes’ focus on environmental and governance issues makes sense. The concept of sustainability has its roots in the environmental movement of the 1960s and regulators typically collect information on food safety. The researchers also acknowledge that the focus on governance is a straightforward way of demonstrating that firms have control over every aspect of the production process.

However, this heavy environmental and governance focus can come at the expense of other elements of sustainable practice. Since the schemes have a lot of clout, their narrow perspective influences what aquaculture producers choose to focus on and where to make improvements. It also has a bearing on what issues are deemed less important. The researchers stress that this a major weakness in certification schemes. Unless it can be addressed, the schemes could unwittingly curb the industry’s sustainability efforts.