Kvarøy, a family-owned salmon producer, whose sites almost straddle the Arctic Circle, has an enviable reputation. Widely viewed as one of the most progressive salmon producers in the country, if not the world, their credentials allow them to sell 90 percent of the 6000 tonnes of salmon they harvest a year for a premium price to Whole Foods Market in the USA.

Although the company might be a mere minnow in an era in which the salmon industry is dominated by multinational leviathans, that has not prevented them from looking into adopting some of the most cutting-edge technology available to fish farmers. The latest foray into futuristic technology comes after they were sent a video by Aquaai, a Californian start-up with unconventional roots. Formed by Liane Thompson, a former New York Times executive producer, and Simeon Pieterkosky, a South African special effects and robotics expert, the fledgling firm had developed a number of fish-like underwater drones for use in a variety of industries, before coming to a conclusion that aquaculture offered the perfect outlet for their biomimicry skills.

“We first looked into working in aquaculture after watching the Frontline documentary A fish on my plate, in which Kvarøy featured,” explains Liane. “Their sustainable approach to farming fits in with our mission to save the seas and we also hoped that – being a relatively small, family-owned company – they might be more accessible than a major corporation. We’ve had dealings with big companies before and they don’t tend to make decisions very quickly.”

“Kvarøy are also industry leaders and have been early adopters of new technologies, so we figured that if they adopted the fish then others would follow,” she adds.

© Aquaai

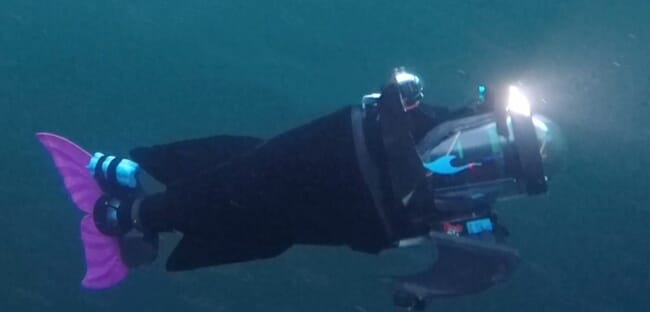

Her first hunch has certainly proved prophetic, and Kvarøy were excited enough by the possibilities offered by having a truly mobile monitoring device in their cages to arrange for a two-week trial of the unit at one of his farm sites in November. Although only a prototype – called Nammu after the Sumerian goddess of the seas – the experience was enough to convince the Norwegians of the potential offered by the device. Indeed, Nammu was equipped with three cameras, including a 360-degree one, an IMU inertial navigation, GPS and avoidance sensors, as well as depth and temperature sensors – the view and readings from which could be viewed from the comfort of the company’s shore base on Kvarøy island.

“Aquaai’s device allows us to get a proper perspective of what’s happening in the cage,” reflects Alf-Gøran Knutsen, Kvarøy ’s CEO. “With our current monitoring equipment if we see any problems – such as dead fish or salmon behaving strangely – we have to physically go a visit the site to try to identify the problems, but with the Aquaai fish in the water we can tell a lot more about what’s going on remotely.”

And both parties were also pleased by how swiftly the robotic unit was accepted by the salmon in the trial cage, suggesting that it does not cause any stress.

© Aquaai

“Normally when we put new objects in the cage – such as biomass measuring frames, for example – the salmon will take several weeks, or even a month, before they interact with it,” says Alf-Gøran. “But we were amazed by how quickly the salmon accepted the Aquaai drone – within minutes it was swimming with the fish. It was very, very impressive.”

Practical benefits

Indeed, given that any number of off-the-shelf sensors can be hooked up to the fish-like platform, he also thinks it will be more economical than the current monitoring set-up, which requires numerous different units to do different roles. He also points to the fact that the improved visuals allow for more accurate feed allocation. Above all, however, he sees the robotic contraption as having huge fish welfare advantages.

“By gathering so much data from right in amongst the fish we’ll be able to detect if there’s anything wrong with the fish or their environment much sooner than we can currently,” says Alf-Gøran. “Which will improve fish welfare and lower any health treatment bills.”

Such was Kvarøy’s faith in the design that they have already ordered 16 of the systems, with the first eight due for delivery in May, followed by the same number in November.

The prototype may have been black, but Alf-Gøran thinks that the fish will accept their robotic cousin – which is about the size of an 8 kilo salmon – regardless of its colour, and this theory is going to be put to the test when the first batch arrives on site in May.

“We’ve asked Aquaai to make them look like clownfish. Not only will this help us see them under the water, but it will also be popular with visitors to the sites,” he chuckles.

Next steps

Despite a comic element, Kvarøy’s commitment to sustainability – and their faith in having their pens patrolled by mechanical Nemo-a-likes – comes with serious credentials, and the company sees the Aquaai units as being part of a wider strategy to operate farms as remotely as possible – not as a means of cutting back their workforce, but as a way of allowing their personnel become increasingly specialised.

“We’re looking into setting up land-based facilities where we can monitor all the sites from and control the feed barges,” explains Alf-Gøran. “Which allows our feed expert to concentrate on feeding and so forth.”

© Aquaai

Meanwhile, following their breakthrough contract with Kvarøy, Liane is now looking forward to developing the project in the year ahead. And she has set her sights on significant expansion.

“The aquaculture market is exploding and there’s a need for technologies that help keep the marine environment healthy. It’s all about precision fish farming and we offer that in an all-in-one system incorporating AI, VR, computer vision and biomimicry. We call it FaaS, as in Fish-as-a-Service. Like a B2B software company, we provide real-time metrics to the farmer; we just rely on the biomimicry hardware for the precision data acquisition aspect,” says Liane.

“I’m very excited about 2018 – we’ve proven our product, achieved the perfect product-market fit and now have customers,” she continues. “We’re planning to fabricate 50 units this year – hopefully Kvarøy will use half of them and we can lease the other half out to other sustainable marine fish farms – and then 400 next year. And we’d like to open an office in Europe – most likely in Norway or Ireland.”

In order to achieve these goals, the company is currently looking to raise further investment.

“We’ve been funded so far by angels from the US, France, and the UK and from funds like GrowthX out of Silicon Valley, but we need to raise more capital now for growth. It’s about finding the right partner.”

© Aquaai

One investment option of interest is the newly-launched aquaculture accelerator Hatch – which is offering pioneering aquaculture projects £25,000 in funding and three months of mentoring from its base in Bergen, in order to help develop and commercialise ideas as well as giving successful applicants access to relevant people in its substantial aquaculture network.

“We’re very interested in HATCH, but the start date for their first intake, April, is probably too early for us since we’ll be very busy with our Nammu platform delivery to Kvarøy,” Liane explains.

Customised programming

The standard Aquaai platform for lease is equipped with pH, depth, tactile and temperature sensors, an IMU, GPS and three cameras – and farmers can access real-time metrics on the Aquaai Control System or web dashboard. Extra features, such as a 360-degree camera or oxygen sensors, will be available. Moreover, Aquaai’s three-man software team can offer for tailor-made programming to control the movements of the fish.

“We’re very much participating in decisions about how to control the fish,” says Alf-Gøran, “and Aquaai have offered us a number of options. As well as the automatic setting, which will be the main function and will ensure that the fish follows the salmon, we will have a manual option and we also need to consider special settings – for example to get the fish to inspect the nets for damage – which can potentially be done at the touch of a button. We’re able to customise the functions.”

© Aquaai

While some commentators might be tempted to dismiss the device as a cute marketing gimmick, it appears that there’s a decent chance that Nammu and her offspring really could help to improve the performance of the industry – in terms of fish health, the welfare of site workers (as it removes the need to use divers to inspect the nets) and economic sustainability; not to mention lessening its impact on the environment. And, in the case of Kvarøy, it might prove a means, not only to help to differentiate their product, but also to help ensure that another generation of the family is able to pursue salmon farming careers.

“The family has been running the company for three generations, and we want to ensure we can hand it over to the fourth – our children – who are currently at school on the island where we’re based. Plenty of companies have put offers in to buy the business, we’ve all built houses on Kvarøy for much more money than they’d fetch if sold – we’re kind of committed,” Alf-Gøran concludes.

It’s an admirable sentiment and it will be interesting to see whether this esoteric ensemble - with its mash-up of Arctic entrepreneurialism, Californian creativity and a pinch of Pixar - is able to transform the salmon farming world.