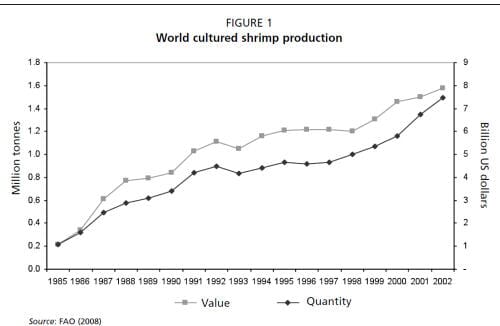

Cultured shrimp production in the world has been growing dramatically over the last two decades, from 0.2 million metric tons (tonnes) in 1985 to 1.5 mmt in 2002; in terms of value it has grown from USD 1 billion to nearly USD 8 billion (Figure 1).

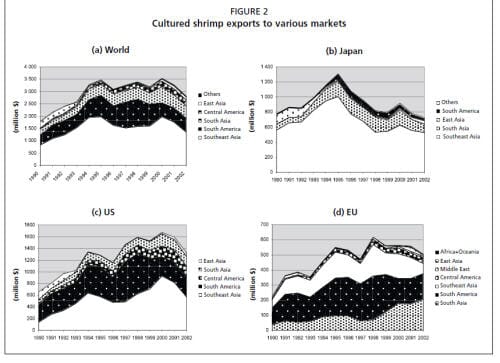

Shrimp farming has been export-oriented in most countries. The three major shrimp export markets are Japan, the United States of America and the European Union, which jointly consumed 90 per cent of the world frozen cultured shrimp exports in the early 2000s (25, 48 and 17 per cent for Japan, the United States of America and the European Union, respectively. See Figure 2).

The report attempts to conduct a global, comparative assessment of 28 major shrimp farming countries’ frozen cultured shrimp export performance in these three major international markets. These 28 countries accounted for 98 per cent of the world cultured shrimp production in the early 2000s.

The methodology for the study can be found here (page 14).

The RCA is revealed comparative advantage. It effectively compares a country's export market share of one product with the entire world export market.

The assessment is focused on Japan, the United States of America and the European Union as the three major international frozen shrimp export markets; other (regional) export markets are aggregated into “other markets”.

Results

The size of the world frozen cultured shrimp export market (in terms of value) almost doubled during the first half of the 1990s, remained stable in the second half, and declined in the early 2000s (Figure 2a).

Southeast Asia has always been the number one exporter in the market, responsible for most of its ups and downs. South America was in the second place in the 1990s, yet it tended to yield the place to South Asia in the early 2000s. In addition to South Asia, Central America is another region with steady growth in frozen cultured shrimp exports. East Asia (primarily China) was the third largest exporter in the early 1990s yet reduced its market share to nearly zero since 1993 until the recent recovery in the early 2000s.

Japanese market

Japan was the largest frozen cultured shrimp export market in the early 1990s, accounting for 39 per cent of world exports by quantity. However, the ratio declined to 34 per cent by the mid-1990s and to 25 per cent by the early 2000s primarily because of shrinking demand for shrimp by Japanese consumers in the context of a stagnated domestic economy. In terms of value, frozen cultured shrimp exports also experienced significant growth in the first half of the 1990s and an equally significant decline in the second half (Figure 2b).

Southeast Asia has always been the dominant exporter to the market, followed by South Asia. South America increased its presence in the market during the second half of the 1990s, but the market was already entering its declining phase. Despite the shrinking size of the market, East Asia (especially China) increased its exports in the early 2000s.

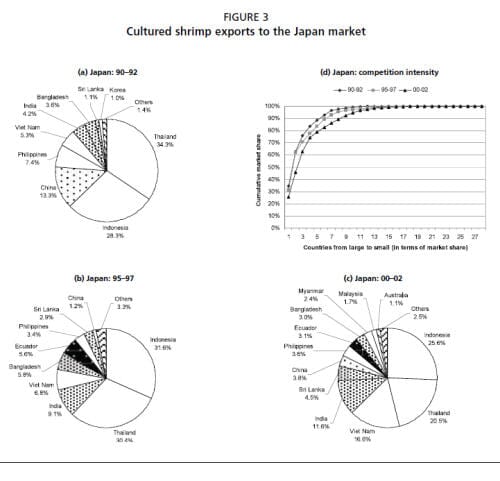

Thailand and Indonesia

In the early 1990s, Thailand and Indonesia were the two largest exporters to the Japan market, meaning that they had a strong revealed comparative advantage (Figure 3a). Their Japan RCA indices were 1.3 and 1.9 respectively, which implies that their Japan market shares were respectively 1.3 and 1.9 times greater than their world market shares.

During the first period, from the early to mid-1990s, Indonesia’s world market share declined from 15 to 13 per cent. Yet its Japan market share has nevertheless increased from 28 to 32 per cent. In other words, despite the size advantage decline, Indonesia was still able to increase its degree of dominance in the Japan market through comparative advantage gains.

Indonesia’s total market share variation in the Japanese market during the first period was 3.3 per cent, which can be decomposed into -1.1 per cent of size variation and 4.4 per cent of structural variation. The negative size variation implies that had Indonesia maintained its comparative advantage pattern during the first period, it would have yielded 1.1 per cent of the Japanese market. Yet, the country has actually gained 3.3 per cent because of the 4.4 per cent of structural variation that reflects its comparative advantage gains in the Japan market.

During the first period, contrary to Indonesia (which had lost world market share yet had gained market share in Japan), Thailand increased its world market share from 27 to 32 per cent yet reduced its Japan market share from 34 to 30 per cent. The 4 per cent of its Japan market share decline is the result of an 8 per cent size gain in tandem with a 12 per cent of structural decline.

During the second period (from the mid-1990s to the early-2000s), Indonesia further reduced its world market share from 13 to 10 per cent while its Japan market share went from 32 to 26 per cent. This 6 per cent decline in Japanese market share was caused by a 2.3 per cent of size decline as well as a 3.7 per cent of structural decline. Thailand had a similar experience and reduced its world market share from 32 to 29 per cent and its Japan market share from 30 to 20 per cent. This 10 per cent decline in Japanese market share was caused by a 3.5 per cent of size decline in addition to a 6.4 per cent of structural decline.

China and the Philippines

In the early 1990s, China and the Philippines were the third and fourth largest exporters to the Japanese market, respectively controlling 13 and 7.4 per cent of the market (Figure 3a). They also had large revealed comparative advantages in the market with RCA indices of 1.1 and 2.0 respectively.

However, both countries reduced their Japan market power significantly during the first period. China lost nearly the entire 13 per cent of its Japan market share because of the collapse of its cultured shrimp production caused by disease outbreaks in 1993. The Philippines expanded its annual cultured shrimp production from 61 000 to 70 000 tonnes during this period; yet this expansion was not sufficient to prevent the decline of its Japan market share from 7.4 to 3.4 per cent. The RCAV indices reveal that their declining dominance in the Japan market was caused completely by a size advantage decline.

With its annual cultured shrimp production rising from 90 000 to 300 000 tonnes, China increased its Japan market share by 2.6 per cent during the second period, which was the result of a 4 per cent size gain together with a 1.4 per cent of structural decline. The Philippines also increased its Japanese market share slightly from 3.4 to 3.6 per cent, which was mainly due to a comparative advantage gain.

Viet Nam

Viet Nam, a rising star in the shrinking Japanese market, increased its market share from 5.3 per cent in the early 1990s to 6.8 per cent in the mid-1990s, and then to 17 per cent in the early 2000s (Figure 3). While the expansion during the first period was mainly a structural effect due to its comparative advantage gain in the Japan market, the expansion during the second period was completely a size effect corresponding to an increase in its world market share from 3.5 per cent in the mid-1990s to 10 per cent in the early 2000s.

Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka

In the early 1990s, Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka held 3.6, 4.2 and 1.1 per cent of the Japanese market, respectively. While India and Sri Lanka had strong revealed comparative advantage in the market with RCA indices of 1.5 and 2.0 respectively, Bangladesh’s RCA index was only 0.5.

During the first period all these three South Asian countries increased their Japan market shares through gains in both size and comparative advantage. During the second period all three countries reduced their comparative advantage in the Japanese market. While India and Sri Lanka can still manage to increase their shares in the market through size advantage gain, Bangladesh (whose size advantage gain was not sufficient to overcome its comparative advantage decline), had to yield some of its Japan market share.

Other countries

Information on other countries’ frozen cultured shrimp export performance in the Japanese market can be found report.

Asian-Pacific dominance

The Japanese market has been dominated by Asian-Pacific countries. Ecuador is the only non-Asian-Pacific country that has ever obtained non-trivial market power in the Japanese market. Its Japan market share was 5.6 per cent in the mid-1990s but it nevertheless declined to 3.1 per cent in the early 2000s (Figure 3).

The Asian-Pacific dominance in the Japan market is evident not only in terms of market power but also in terms of comparative advantage – Brazil is the only non- Asian-Pacific country that has ever had strong comparative advantage in the Japanese market.

However, not all Asian countries have strong comparative advantage in the Japanese market. Bangladesh is the only Asian country that never enjoyed strong comparative advantage. Iran (Islamic Republic of) and Saudi Arabia in the Middle East had only a transitory strong comparative advantage in the mid-1990s. Thailand had a strong comparative advantage in the early 1990s but it has weakened since the mid-1990s. Interestingly, Korea (the closest neighbour to Japan) had only a weak comparative advantage by the early 2000s.

Competition intensity

The Japanese market has become increasingly competitive in the sense that market shares have been distributed more and more evenly across countries. While over 60 per cent of the market was controlled by only two countries (Indonesia and Thailand) in the early and mid-1990s, Viet Nam also emerged as a top supplier by the early 2000s (Figure 3). In general, the cumulative market share curves in Figure 3d indicate that the Japan market share has become less concentrated in the early 2000s than in the early 1990s.

Comparative advantage variation

According to the RCAV indices, the following countries have gained comparative advantage in the Japanese market during both study periods: Myanmar, Malaysia and the Philippines in Southeast Asia; Nicaragua in Central America; and Ecuador in South America. On the contrary, Thailand, Republic of Korea, Mexico and Colombia have reduced their comparative advantage.

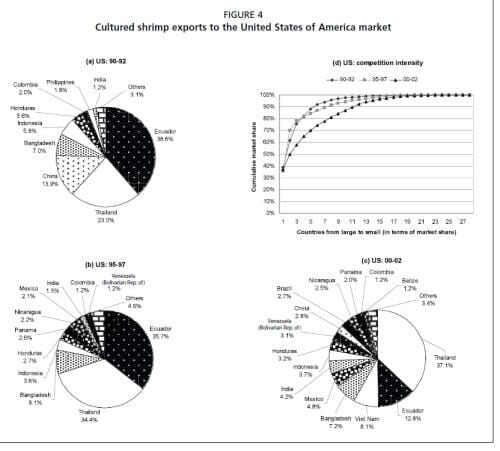

The US market

Rapid economic growth in the United States during the 1990s increased the country’s consumption of the world frozen cultured shrimp exports from 38 per cent in the early 1990s to 40 per cent in the mid-1990s, and then to 48 per cent in the early 2000s, when it became the largest international frozen cultured shrimp market (Figure 2c).

Cultured shrimp export comparative advantage: a global assessment 27 South America and Southeast Asia are the two major exporters to this market; yet both have reduced their exports recently.

Central America and South Asia have relatively smaller cultured shrimp exports to the United States market; however, their respective shares have been increasing in the most recent years. East Asian (mainly China) exports to the United States were at the same level as Southeast Asia in the early 1990s; this market share collapsed to nearly zero since 1993 as a consequence of declining shrimp farming.

The recovery of the Chinese industry in the early 2000s led to a reactivation of shrimp exports. China became the second largest frozen shrimp exporter (in terms of quantity) to the United States in 2003.

Ecuador and Thailand

Ecuador and Thailand are the two most dominant exporters to the United States. market (Figure 4). In the early 1990s Ecuador accounted for 22 per cent of the world market while Thailand represented 27 per cent. In contrast, Ecuador’s share in the United States (39 per cent) exceeded that of Thailand (23 per cent). This reflects Ecuador’s much stronger comparative advantage in the United States market (with an RCA index of 1.7) than Thailand (with an RCA index of 0.8).

During the first period, Thailand raised its United States market share significantly by 11 per cent (from 23 to 34 per cent) through 5 per cent of size gain and 6 per cent of structural gain. In contrast, Ecuador reduced its United States market share from 39 to 36 per cent because of its declining comparative advantage. During the second period, Ecuador’s United States market share declined further to only 13 per cent because of a size-advantage decline caused by shrimp diseases that reduced the country’s shrimp production by half.

Thailand has also reduced its size advantage in the United States market during the second period; however, its United States market share nevertheless increased from 34 to 37 per cent through comparative advantage gains.

China

In the early 1990s, China controlled 14 per cent of the United States market where it had a strong comparative advantage (RCA index = 1.1). However, as its world market share fell from 12 per cent in the early 1990s to 0.8 per cent in the mid-1990s (due to the disease-induced shrimp farming collapse in 1993), its United States market share declined even more severely (from 14 to 0.5 per cent). According to the RCAV indices for the first period, China’s comparative advantage in the United States declined but it then increased in both the Japanese and EU markets.

During the second period, China increased its world and United States market shares to 3.3 and 2.8 per cent, respectively.18 RCAV indices during this period indicate that China has gained comparative advantage in the United States market in detriment of the Japan and EU markets.

Viet Nam, India, Mexico and Brazil

Viet Nam, India, Mexico and Brazil have been performing as four rising stars in the United States market, jointly supplying 20 per cent of exports in the early 2000s.

Viet Nam increased its United States market share from less than 1 per cent in the mid-1990s to 8 per cent in the early 2000s through 2 per cent of size and 6 per cent of structural gain. India held 1.2 per cent of the United States market in the early 1990s and then 1.5 per cent in the mid-1990s through size gains; its share increased significantly to 4.2 per cent in the early 2000s through 1.1 per cent of size and 1.6 per cent of structural gain.

Mexico has maintained a very strong comparative advantage in the United States market with an RCA index consistently above 2. Its size advantage gains driven by rapid shrimp farming growth increased its United States market share from 0.5 per cent in the early 1990s to 2.1 per cent in the mid-1990s and 4.8 per cent in the early 2000s. On the other hand, Brazil increased its annual cultured shrimp production significantly from 3 000 tonnes in the mid-1990s to 42 000 tonnes in the early 2000s. Accordingly, its United States market share increased from nearly zero to 3 per cent through 1.8 per cent of size and 0.9 per cent of structural gain.

Other countries

Information on other countries’ frozen cultured shrimp export performance in the United States market can be found here.

Regional dominance in the United States market

As far as market share is concerned, South America was the most dominant exporter to the United States market in the early and mid-1990s, controlling 42 per cent of the market. Yet this share had declined to 22 per cent by the early 2000s; by then, Southeast Asia was the most important supplier. The region increased its United States market share from 31 per cent in the early 1990s to 39 per cent in the mid-1990s and 50 per cent in the early-2000s. Central America and South Asia also gained market power in the United States during both periods.

With regard to revealed comparative advantage, the Latin American dominance in the United States market is as evident as the Asian-Pacific dominance is in the Japan market. China in the early 1990s, Thailand in the mid-1990s and early 2000s, and Saudi Arabia in the early 2000s have been the only non-Latin American countries to enjoy strong comparative advantage in the United States market. On the other hand, Brazil in the mid-1990s and Colombia in the mid-1990s and early 2000s were the only Latin American countries to exhibit weak comparative advantage in the United States market.

Competitive intensity As previously observed in Japan, the United States market has become increasingly competitive, especially in the early 2000s (Figure 4d). While only two countries (Ecuador and Thailand) controlled 70 per cent of the United States market in the mid- 1990s, five countries accounted for that share in the early 2000s. Similarly, while six countries controlled 90 per cent of the market in the early 1990s, 12 countries accounted for the same market share in the early 2000s.

Comparative advantage variation

Thailand, Viet Nam, Nicaragua and Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) exhibited comparative advantage gains in the United States. market during both periods. Belize, Bangladesh and the Republic of Korea enjoyed comparative advantage gains during the first period but declines during the second one. Brazil, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Australia, India, Sri Lanka and China experienced a decline in comparative advantage during the first period yet recorded gains during the second.

Most of the countries with falling comparative advantage during both periods (i.e. Honduras, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Ecuador and Colombia) are in Latin America; the only exception is the Philippines.

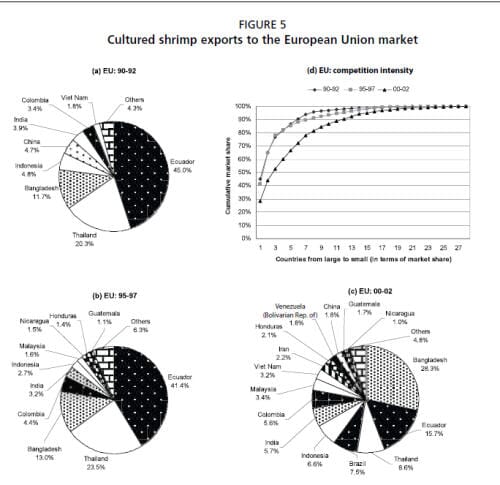

The European Union market

Relative to Japan and the United States, the EU market has been relatively small, absorbing 15, 16 and 17 per cent of the world frozen cultured shrimp exports in the early 1990s, mid-1990s and early 2000s, respectively. However, its absolute size grew significantly through the late 1990s (Figure 2d). As compared to Japan and the United States, the EU market has been more competitive in the sense that market shares have been distributed more evenly across exporters (Figure 5).

South America was the largest exporter to the market in the 1990s, followed by Southeast Asia (Figure 2d). Both regions reduced their EU exports in the early 2000s while South Asia became the largest exporter by the same time period. The market shares of Central America, Middle East and East Asia have been relatively small.

Ecuador, Thailand and Bangladesh

Ecuador, Thailand and Bangladesh were the three most dominant countries in the EU market in the early 1990s. Ecuador held 45 per cent of the market in the early 1990s and was the number one exporter (Figure 5). Its share fell slightly to 41 per cent in the mid-1990s because of a declining comparative advantage, and then it dropped further to only 16 per cent in the early 2000s because of a declining size advantage.

Thailand was the second largest exporter to the EU market in the early and mid- 1990s and the third largest in the early 2000s (Figure 5). Yet its comparative advantage in the market has been weak and declining. Bangladesh increased its EU market share from 13 per cent in the mid-1990s to 28 per cent in the early 2000s when it replaced Ecuador as the number one exporter. A gain in comparative advantage was the main driving force behind this 15 per cent surge; in contrast, the country’s world market share increased only slightly from 8.7 to 9.5 per cent during the same period.

Brazil

In addition to Bangladesh, Brazil recorded large comparative advantage gains during the second period. Seven points of its 7.5 per cent market share gain during the second period was due to gains in comparative advantage.

Colombia, India and Indonesia

The shares of Colombia, India and Indonesia in the EU market have been relatively large and stable. Colombia had a strong and increasing comparative advantage during the entire study period, which helped increase its market share from 3.4 per cent in the early 1990s to 4.4 per cent in the mid-1990s and 5.6 per cent in the early 2000s.

Indonesia reduced its market share from 4.8 per cent in the early 1990s to 2.7 per cent in the mid-1990s because of further declines in its already weak comparative advantage position.

Yet a subsequent comparative advantage gain during the second period helped raise the country’s market share to 6.6 per cent in the early 2000s. India reduced its EU market share from 3.9 to 3.2 per cent during the first period because of a decline in comparative advantage (from strong to weak) and then raised it to 5.7 per cent in the early 2000s because of a size advantage gain.

Other countries

Information on other countries’ frozen cultured shrimp export performance in the EU market can be found here.

Regional dominance in the European Union market

With regard to market power, three regions reduced their market shares during the entire study period (South America from 50 to 31 per cent, Southeast Asia from 27 to 23 per cent, and East Asia from 4.8 to 2.1 per cent); the other 5 regions increased their shares (South Asia from 16 to 34 per cent, Central America from 1.9 to 6.3 per cent, the Middle East from virtually zero to 2.2 per cent, Africa from 0.1 to 0.9 per cent, and Oceania from 0.2 to 0.4 per cent).

With regard to revealed comparative advantage, the EU market is more diversified than the Japanese and United States markets. While countries with strong comparative advantage in the Japanese and United States markets are concentrated in the Asian- Pacific and Latin American regions respectively, there has been at least one country from every region (except East Asia) with strong comparative advantage in the EU market during the entire period from the early 1990s to the early 2000s (Costa Rica and Guatemala in Central America; Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) in South America; Iran (Islamic Republic of) in the Middle East; Bangladesh in South Asia; Malaysia in Southeast Asia; New Caledonia in Oceania; and Madagascar in Africa). Even South Korea from East Asia enjoyed very strong comparative advantage gains by the early 2000s.

Five out of nine countries with weak comparative advantage in the EU market during the entire study period are from Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam); the other six countries are Mexico, Panama, China and Sri Lanka.

Competitive intensity

Similar to the Japanese and United States markets, the EU market has also become increasingly competitive, especially in the early 2000s (Figure 5d). While the four top countries controlled over 80 per cent of the market in the mid-1990s, eight countries accounted for the same market share in the early 2000s.

Comparative advantage variation

According to the RCAV indices, New Caledonia, Malaysia, Colombia, Honduras, China, Guatemala, Peru, Madagascar, Mexico and Costa Rica were the 10 countries with the largest comparative advantage gains in the EU market during the first period. For the same period, Saudi Arabia, Nicaragua, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Iran (Islamic Republic of), Belize, Australia, Brazil, India, Sri Lanka and Viet Nam were the 10 countries with the largest comparative advantage declines.

During the second period (from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s), Republic of Korea, Brazil, Bangladesh, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Guatemala, Madagascar, Belize, Indonesia, Colombia and Honduras were the 10 countries with the largest comparative advantage gains in the market, while Thailand, New Caledonia, Saudi Arabia, China, Nicaragua, Myanmar, Panama, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Peru, Malaysia and Mexico saw declines in their comparative advantage.