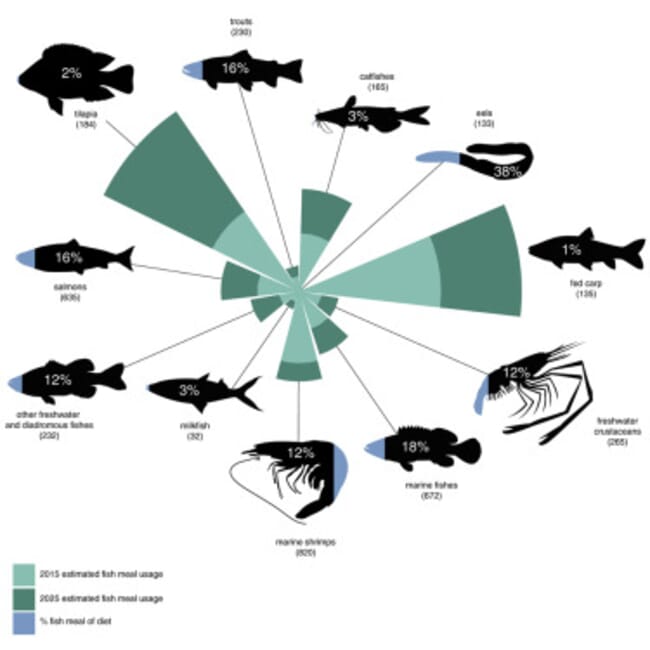

The estimated aquafeed volume demand (millions of tons) of the major fed-aquaculture species groups in 2015 and 2025, and the use of fish meal in the diet of each group in 2015 (represented by the blue portion of each animal). The values (percentage) inside each species group symbol are the estimated fish meal inclusion in 2015. The values in brackets beside each species group symbol are the estimated volume of fish meal included in the diets in 2015 (thousands of tons). Data sources: fish meal proportion in diets in 2015; estimated aquafeed volume demand. © Hua et al.

So argue the authors of a recent study, which looks into the relative sustainability, scalability and nutrient contents of a number of emerging replacements for fishmeal and fish oil in aquafeeds.

The researchers point out aquafeed sector has grown at a more rapid pace than fed-aquaculture production.

“There has been a four-fold increase in fed-aquaculture production from 12.2 million tons to 50.7 million tons from 1995 to 2015. In parallel, the increase in aquafeed production was six-fold, from 7.6 million tons to 47.7 million tons from 1995 to 2015,” they note.

“Approximately 70 percent of the aquatic-based production of animals is fed aquaculture, whereby animals are provided with high-protein aquafeeds. Currently, aquafeeds are reliant on fish meal and fish oil sourced from wild-captured forage fish. However, increasing use of forage fish is unsustainable and, because an additional 37.4 million tons of aquafeeds will be required by 2025, alternative protein sources are needed. Beyond plant-based ingredients, fishery and aquaculture byproducts and insect meals have the greatest potential to supply the protein required by aquafeeds over the next 10–20 years,” they argue.

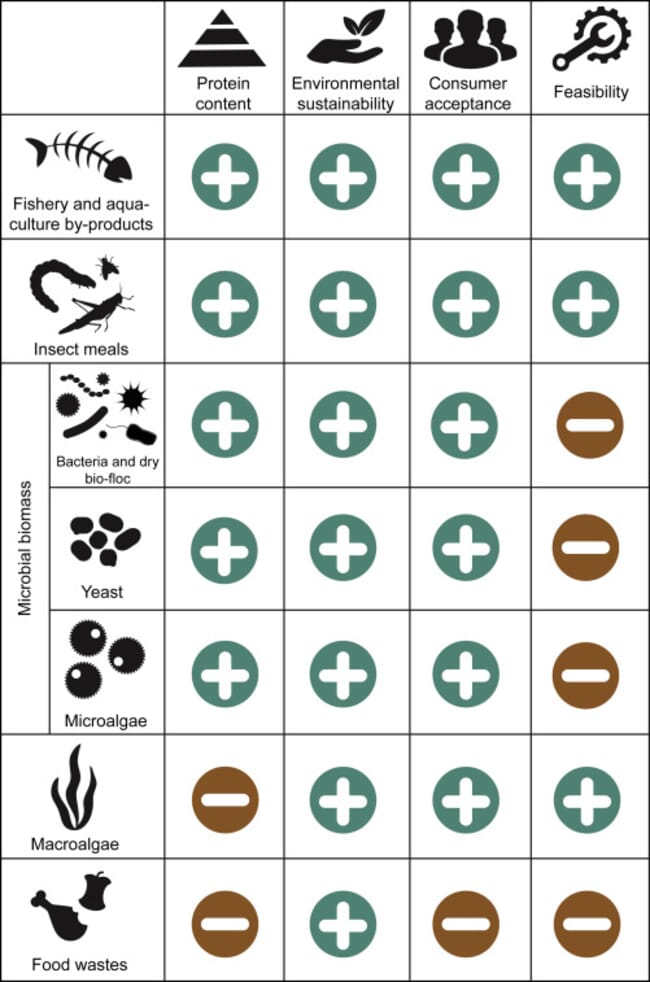

While there are other promising candidates, notably food waste, some of the other emerging sources of proteins have poorer prospects for making a difference in the short- to medium-term, due to certain shortcomings.

“Food waste also has potential through the biotransformation and/or bioconversion of raw waste materials, whereas microbial and macroalgal biomass have limitations regarding their scalability and protein content, respectively,” they explain.

“The greatest challenges to alternative protein sources in aquafeeds include variable protein content and the feasibility of increasing production, which is a function of available processing technologies, cost, and scalability. Consumer acceptance also varies among these raw materials,” they add.

However, despite these challenges, they do see “enormous potential for technological improvements to consistently produce high-quality alternative protein products with enhanced nutritional profiles, while economies of scale can result in improved price competitiveness.”

They also suggest that no single source of proteins is likely to emerge to replace forge fish.

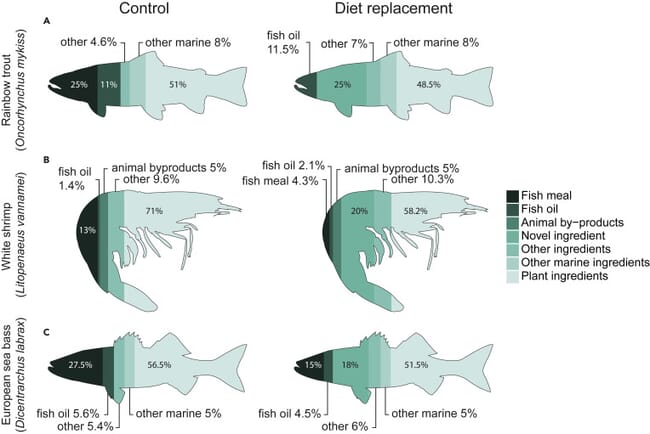

“Multiple protein sources can also be used in combination to benefit from their complementary nutritional profiles. Feed supplements can also be used to balance the nutrient composition of the feeds and functional ingredients can be used to facilitate the replacement of fish meal with alternative ingredients. Furthermore, using multiple protein sources allows flexibility in feed formulations when ingredient prices fluctuate, as feed manufacturers often use cost as a determinant in selecting ingredients,” they observe.

The broad-level qualitative assessments of alternative protein sources were based on a combination of the current-day realities and the future potential (10–20 years) of each protein source. Positive (+) represents a protein source with high potential to meet demand, while negative (−) represents a protein source that has obstacles that will need to be overcome before development. The assessments were subjective and based on a relative comparison with fish meal from wild-capture fisheries. The assessment for “feasibility” was determined by considering the economics of commercial-scale production, the relative limit of the resource, the likelihood of meeting consistent supply, the short-term prediction of commodity price, and the legal ease of implementation. © Hua et al

The complete or partial replacement of fish meal using alternative protein sources demonstrated equivalent or higher growth in the animals than the control fish meal diets. Shading represents the proportion of dietary ingredients. (A) Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) were fed a control diet with 25% fish meal or an experimental diet with 25% yellow mealworm protein meal.61 (B) Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) were fed a control diet with 13% fish meal or an experimental diet with 20% microbial biomass and 4.3% fish meal.66 (C) European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) were fed a control diet with 27.5% fish meal or an experimental diet with 18% freeze-dried microalgae and 15% fish meal.67 © Hua et al

The researchers also touch on ways to increase aquaculture without requiring a parallel increase in marine ingredients or their equivalents – suggesting that increasing consumer awareness of the relative merits of lower-trophic freshwater fish species, such as catfish, tilapia, compared to carnivorous species like salmon and shrimp could help.

“This sector has the highest potential to mitigate the use of forage fish by mid-century,” they suggest.

Further information

The full article, "The Future of Aquatic Protein: Implications for Protein Sources in Aquaculture Diets", was published in open access format in the One Earth journal.