“It’s satisfying to see that many people are seeing the potential of algae and plankton,” says Gunvor Øie, manager of the centre. “Our aim is to contribute towards establishing a new biomarine industry in Norway. Some people believe that algae and plankton will be the new oil.”

The Plankton Centre is not yet complete, but last year received just over NOK 19 million (£1.8m) from the Research Council of Norway to construct laboratories in which to develop concepts for future commercialisation. SINTEF is administering the centre, together with NTNU, and the funding has made it possible to develop new infrastructure in the laboratories, which contain microalgae (single-celled algae), macroalgae (seaweeds) and zooplankton (including copepods, amphipods and bristle worms). The centre aims to identify methods of production, harvesting and processing of these small organisms.

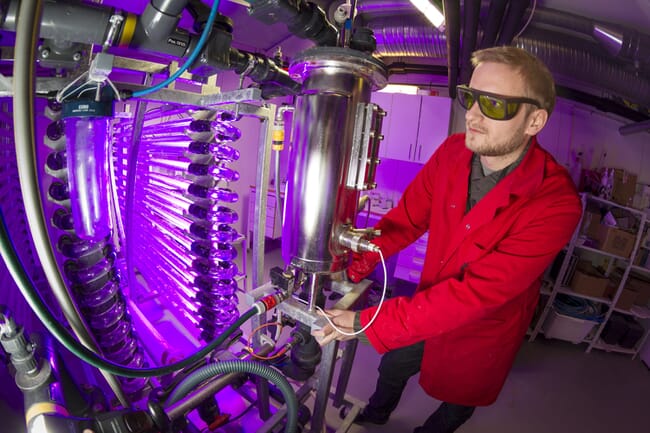

© SINTEF Ocean

Norway aims to expand its aquaculture sector five-fold by 2050, with a goal to produce 5 million tonnes of salmon a year by 2050. In order to achieve this, the production of microalgae containing high concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids is likely to play a key role.

“Much of the fish feed is [currently] produced on land and contains too little of the beneficial fatty acids,” says Jorunn Skjermo, Senior Research Scientist at SINTEF, and manager of the COMPLETE project. “With a larger proportion of algae in the feed, its nutrient value will be enhanced and the fish will be able to feed on natural and healthy food.”

During this project, SINTEF is working together with a biogas facility in Skogn, Nord-Trondelag county, which is aiming to cultivate algae in the plant’s wastewater. The researchers have already started test production of microalgae in laboratories at the Plankton Centre, which is located on SINTEF Ocean’s premises at Brattøra in Trondheim.

“The waste water we used for the initial experiments was strongly discoloured, and this caused problems for microalgae production,” says Matilde Skogen Chauton, a Senior Research Scientist at SINTEF Ocean. “We are now testing water produced by a different stage of the process at Skogn, which contains less of the discolouring substances. We hope that this will make production much easier.”

Working with the oil industry

Statoil has contracted the centre to carry out oxygen measurements on cod eggs and larvae, as well as the cultivation of feed organisms. The main aim of these experiments is to study and document the impacts on relevant marine species of chemicals (synthetic polymers) that may be used in connection with improved oil recovery.

“From our point of view it is important that our suppliers of services and research projects have adequate access to marine plankton species that can be used in standard toxicity tests, as well as species that are relevant in the marine environment,” says Statoil’s Randi Hagemann.

Aquafeed potential

Commercialisation is a key part of the efforts being made at the centre, and one of the companies that has emerged from it is called C-Feed, which sells feed ingredients for marine finfish.

“What makes salmon larvae special is that they can feed on pellets right from the start,” says Tore M Remman, CEO of C-Feed. “Most other fish species need live feed in order to survive.” Plankton production takes place on land, and the company sells fresh eggs and plankton.

“Live feed for a variety of fish species may become big business overseas,” says Remman. “In Norway we sell feed for cleaner fish, among others.”

The feed supremo appreciates having access to the Plankton Centre as a means to develop further aquafeed products.

“We need more research into how to breed new species such as tuna,” he says. “We’ve already carried out experiments with our products and have obtained good results. But we still have some way to go, so the Plankton Centre will also be important to us in the future.”