HABs kill millions of fish – both in the wild and in fish farms – every year, but until recently the reason why seemingly harmless algae could become toxic was poorly understood.

© John Innes Centre

The breakthrough came from an unlikely source – the John Innes Centre in Norfolk – an institution better known for its research into carbon studies.

“It was a case of serendipity on a Sunday afternoon,” explains the centre’s Prof Rob Field who led the study. “One of my colleagues happens to be a keen angler, and regularly fishes on the Norfolk Broads. The Broads often experience fish kills caused by blooms of Prymnesium parvum (golden algae) and my colleague’s angling friends asked him – as a scientist – to look into ways to solve this problem.”

This prompted the start of a study which made the team begin to appreciate the global scale of the problem.

“Golden algae is not just an issue in the Broads (which are brackish) it’s primarily a marine species and is an issue for fish farmers all over the world – from ponds in Texas to coastal Norway,” Prof Field adds.

In order to come up with some form of practical measures Prof Field’s team needed to explore a number of different issues.

“We had to look into why the algae sometimes blooms, why it can become toxic and what the toxins it produces are,” he explains.

And they discovered that the algae wasn’t toxic under normal conditions.

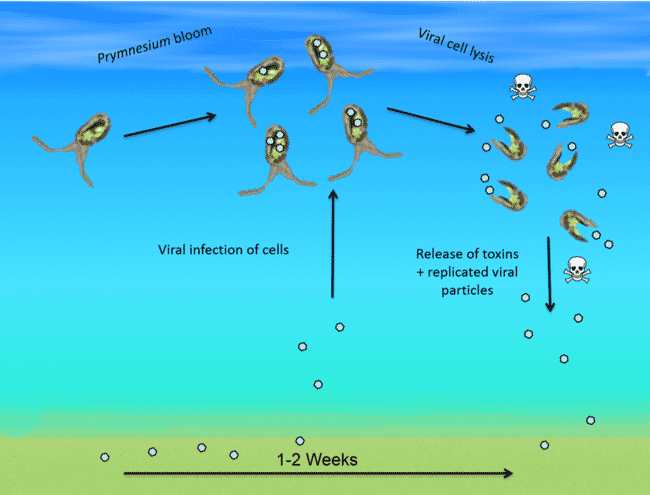

“It turned out the blooms were becoming toxic when infected with a virus which kills the algae and effectively lyses it, which makes it toxic to any gill-breathing animals,” Prof Field explains.

“The algae are not killing the fish directly – under normal conditions when the algae die slowly it’s completely harmless. The risk factor is when a bloom becomes infected with the virus, causing a mass die-off of the algae and a high volume of toxins being released,” he adds.

© John Innes Centre

His next challenge was to come up with a practical means of controlling the blooms or at least preventing them from becoming infected.

The team came up with an effective means by adapting a solution that was already being used by the Environment Agency to help aerate the Broads during summer.

“The EA use hydrogen peroxide, which is a powerful oxidising agent, to aerate the water at times – like summer – when the oxygen partial pressure of the water is too low. We’ve found that by tinkering with the peroxide concentration we can also kill the golden algae and destroy the toxin – it’s really, really simple chemistry, but at the same time a radical rethink of how to contain an algal bloom,” Prof Field reflects.

The discovery is particularly exciting for aquaculture producers operating in contained waterways, such as ponds – all the more so given that the researchers have used their new knowledge of the mechanism behind HABs to the latest environmental DNA monitoring techniques.

“These give us 2-3 days warning that a harmful bloom might occur,” says Prof Field.

However, while the use of H2O2 might not be practical for staving off HABs in larger bodies of water, such as most marine settings, the research breakthrough does increase the chances of finding a means to stave off HAB challenges more widely.

“The results mean that we can now accurately assess the risk posed by algal blooms,” observes Prof Field. And it also gives farmers a few crucial days to react to any impending HABs.