Introduction

In 2000, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) defined the ecosystem approach (EA) as “a strategy for the integrated management of land, water and living resources that promotes conservation and sustainable use in an equitable way” and chose the EA as the primary framework for the CBD implementation; stressing a multidisciplinary collaboration to achieve the CBD objectives.

In the fishery sector, the ecosystem approach has been similarly accepted as one of the key “vehicles” for developing and improving fisheries management. There have been, however, a multitude of variations on the definition of an EA; some have focused more on the natural science ecosystem components, while others stressed a more holistic and integrated (interdisciplinary) interpretation. In response to an international call for assistance to clarify what is meant by an EA in the fisheries context, the FAO published guidelines on the ecosystem approach to fisheries in 2003.

Recognizing the wide range of interpretations of the approach, the FAO proposed the following definition, which is aligned with the more general EA but seeks a pragmatic balance by focusing the EAF on aspects within the ability of fisheries management bodies to implement, even while recognizing the fisheries sector’s responsibility in collaborating in a broader multisectoral application of the EA:

an ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF) strives to balance diverse societal objectives, by taking account of the knowledge and uncertainties of biotic, abiotic and human components of ecosystems and their interactions and applying an integrated approach to fisheries within ecologically meaningful boundaries.

It is important to note that the concepts and principles of an EAF are not new – they are already either explicitly contained in a number of international and national instruments and agreements (e.g. as in the case of the CBD above) or implicitly manifested through local, regional, and international actions – whether or not these explicitly used the term “EAF”.

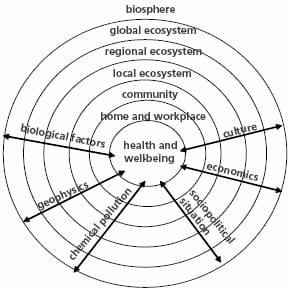

In particular, other sector-specific applications of the EA include those to urban management, to drylands, to forestry, and to human health. Each of these is naturally interpreted from the perspective of the particular sector – albeit generally incorporating the trio of ecological, social and economic considerations. For example, the ecosystem approach to human health incorporates “human health considerations into the dynamic interrelations of ecosystem analyses” and “places humans in the centre of a series of nested spheres, which can negatively and positively influence health and well being” as shown below.

From the above discussion of EA and EAF concepts, the next step lies in understanding what the approach means in practice. This report is grounded in the belief that the application of the EAF must be holistic, integrated, participatory, and adaptive, and builds on the EAF Guidelines by providing here a focus on the human dimensions (i.e. political, legal, cultural, social, economic and institutional aspects) of such an application.

Specifically, this report acknowledges the following “entry points” of human considerations – social, economic and institutional – into the implementation of an EAF:

- Social, economic and institutional objectives and factors may be driving forces behind the need for EAF management;

- The costs and benefits of applying the EAF, whether to individuals or to society, have social, economic and institutional impacts and implications;

- Social, economic and institutional instruments are all crucial for successful implementation of the EAF; and

- Social, economic and institutional factors present in fishery systems can play either supporting or constraining roles in EAF implementation.

In other words, social, economic and institutional elements can be simultaneously drivers, constraints, and/or supports for EAF implementation, and in addition, there can be social, economic and institutional outcomes of that implementation. All of these “entry points” need to be taken into account in EAF discussions.

Basically, the EAF takes place in the context of societal and/or community objectives, which inherently reflect human aspirations and values. As implementation of the EAF is a human pursuit, the social and economic forces at play need to be understood, the incentives and disincentives driving human behaviour need to be investigated, and actions need to be undertaken in terms of fishery governance and corresponding institutional arrangements – all so that management can induce outcomes in the fishery compatible with societal objectives.

In addition, although focusing on the fisheries sector, EAF will have inter and intra-sectoral process components that must be taken into account, even if beyond the scope of the fisheries managers’ direct responsibility. However, the more integrated or cross-sectoral the approach taken is, the more likely the attainment of sustainable development goals.

Certainly, the need to incorporate human components of the fishery system into an ecosystem approach is clear as humans are part of, depend on, and affect the ecosystem in which they live, work, and play. The challenge lies in implementation. This report seeks to provide support in meeting that challenge, by consolidating a range of available knowledge and experience relevant to EAF implementation, from social, economic and

institutional viewpoints, and examining the manner by which these aspects can be practically incorporated, as well as highlighting the remaining gaps in both knowledge and implementation.

Understanding the complexities and contexts

In any given fishery in which implementation of EAF management is being planned, it is important to understand the current state of the fishery and its natural and human environment (the starting point) – the context in which EAF is being developed. This must be the first step in interpreting the EAF for the given situation.

For example, knowing the context will help clarify if the particular EAF will be:

incremental or wholesale, intersector or intra-sectoral, local or international, involving intensive scientific research or relying on the best available information, etc. Establishing this EAF context will involve not only understanding the fishery/ecosystem from both the natural science and human perspectives, but also society’s goals and values with respect to ecosystem goods and services; the socio-economic context (at the micro and macro levels) in which the fishery operates; the policy and institutional frameworks in place; as well as the political realities and power dynamics affecting the governance of resources. A good understanding of these issues and other realities surrounding the use of aquatic resources is essential to guide EAF policies, objectives and plans – in their absence, policies and plans may very likely fail to assist in the move towards sustainable fisheries.

The human aspects that play a role in determining an EAF include the power and governance structures in place, the economic “push” and “pull” mechanisms driving the fishing activities, the socio-cultural values and norms associated with fishing, and the external contexts (e.g. global markets, natural phenomena, emergencies, and political changes) that impact on our ability to manage our fisheries. Chapters 2 through 4 describe many of the human dimensions and the techniques available assisting their evaluation, surrounding the EAF context.

The context also includes the motivation for the EAF. The list of potential factors driving fisheries managers, a community, or a society to adopt the EAF is as extensive and varied as the list of potential reactions to these drivers. These drivers may include human as well as biological factors, at any scale (from local to international), and may be reactionary or forward looking. For example, countries may be reacting to international treaties or conventions, to crises and conflicts within and around the fisheries, or to lobbying from special interest groups. Alternatively, countries may be adopting the EAF as part of a future framework for achieving sustainable development.

Key concepts and issues

This part of the report discusses (i) the idea of an EAF management, highlighting the role of human aspects, (ii) key underlying issues in implementing the EAF (i.e., boundaries, scale and scope), and (iii) the relationship of the EAF to complementary approaches that also include broader looks at the components and interactions in the fishery (the livelihoods approach and integrated management).

EAF management

The word “management” has been purposely left out of the term “EAF” as the approach is not limited to management but applies to policy, legal frameworks, development, planning, etc. However, some of the early motivation for the EAF lay in the recognition that single-species stock assessment and management (what is referred to in the EAF Guidelines as “Target Resource Oriented Management” or TROM) could be insufficient and that there was a need to look more broadly at the surrounding ecosystem – prey and predator spspecies, oceanographic effects, environmental impacts of other human activities, etc.

This broadening of attention from individual species to multiple fish species and ecosystems includes the management of a range of human interactions with the fishery ecosystem, whether technical, economic, social or institutional. Furthermore, the EAF must deal to some extent with interactions with other uses of the aquatic environment, and with linkages throughout the fishery system (e.g. to the post-harvest sector and the socioeconomic environment of the fishery).

Overall, then, the EAF must incorporate whatever ecosystem and human considerations are of direct relevance to fisheries management, i.e. which will typically need to be taken into account for effective fisheries management. This is not really any different from the situation in conventional fishery management, which also needs to take human considerations into account to be successful (even if this has not always been achieved – see, e.g. Charles, 1998a; Cochrane, 2000). However, as pointed out in the EAF Guidelines, the challenge is that much greater in EAF, given the consequent broadening of attention that is needed, to include aspects of ecosystems and of corresponding human elements.

There has been some progress in meeting this challenge, both in terms of moving towards an improved understanding of social, economic and institutional aspects relating to fishery management (and EAF in particular), and in terms of developing tools and instruments to improve management by taking this understanding into account. On the other hand, even with conventional management and certainly with EAF, there remains a gap between words and deeds when it comes to incorporating such aspects into fishery management. One indication of this gap is the recurring pleas from social scientists, over the past several decades, for increased progress in this direction.

The efforts of countries to address aspects of EAF have arisen in three main categories:

- Issue-based technically-oriented actions, such as:

- reducing the impacts on bycatch species;

- increasing the selectivity and decreasing the harmful impacts of fishing gear;

- protecting and restoring critical habitats and species interactions;

- Implementation of institutional changes as part of national EAF measures, such as:

- changing fisheries policies to include EAF and precautionary principles;

- increasing stakeholder involvement in fisheries management;

- creating multidisciplinary and/or intersectoral advisory groups/committees;

- taking part in multicountry projects aiming at harmonizing management at the large marine ecosystem level;

- using community-based management tools; and

- Broadening the nation’s information systems to include:

- multispecies or ecosystem models (looking at changes across the food web);

- bio-economic models (looking at changes across the fish and the fishing industry);

- incorporated qualitative and quantitative models, such as people’s perceptions;

- multidisciplinary information in risk assessments and cost-benefit analyses;

- local and/or traditional knowledge;

- integrated indicator systems;

- participatory information systems.

While there seem to be few examples to date of a comprehensive adoption of the EAF in all aspects of the fishery system (i.e. from the policy realm to implementing adaptive management operationally, and also adjusting institutional and other supporting frameworks), there have been many incremental moves, and the momentum is building towards broader use of the EAF in many fisheries.

Social, economic and institutional considerations in EAF A wide range of social, economic and institutional considerations may be relevant to the implementation of an EAF:

- First, EAF must take place in the context of societal and/or community objectives, which inherently reflect human aspirations and values.

- Second, as EAF takes into account interactions between fisheries and ecosystems, this includes a wide range of complexities relating to human behaviour, human decision making, human use of resources, and so on.

- Third, implementing the EAF is a human pursuit, with implications in terms of the institutional arrangements that are needed, the social and economic forces at play, and the carrots (incentives) and sticks (e.g. penalties) that can induce actions compatible with societal objectives.

Indeed, the latter aspect – that of institutional arrangements – highlights the need in EAF for structured decision making processes, grounded in the accepted set of societal objectives, and governed by a suitable set of operating principles – what has been referred to as a “fishery management science” approach (Lane and Stephenson, 1995). The fishery objectives being pursued underlie the criteria for judging success, which are in turn needed in order to decide on the best management approach. Parallel to the objectives are principles governing fishery management, which influence the choices made of policy and management measures to best meet the stated objectives – these are drawn from a range of sources such as national legislation, international conventions, and “approaches” including the precautionary approach and the ecosystem approach.

Such processes must take place in a world of complexity, and the hope is that EAF provides an effective vehicle to better recognize and address the wide range of complexities in fisheries, complexities that can bear directly on the success of fisheries management. Social, economic and institutional aspects contribute as much to the set of complexities faced within fishery management as do those relating to fish species and the aquatic environment itself. For example, a fishery typically faces the complexities of: (a) multiple and conflicting objectives; (b) multiple groups of fishers and fishing fleets and conflicts among them; (c) multiple post-harvest stages; (d) complex social structures, and socio-cultural influences on the fishery; (e) institutional structures, and interactions between fishers and regulators; and (f) interactions with the socioeconomic environment and the larger economy (Charles, 2001).

EAF, the livelihoods approach and integrated management

Relationships among the EAF, the LA and IM

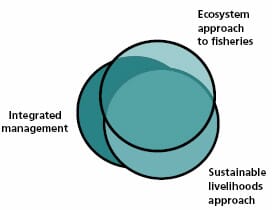

The move towards a broader approach to fisheries management reflects the fundamental goal of sustainable development, in keeping with WSSD objectives. To this end, it is useful to look at the ecosystem approach to fisheries in comparison with two major multisectoral thrusts in global discussions relating to natural resource and spatial area management: the livelihoods approach and the integrated management approach. These complementary and overlapping approaches, and interactions with the EAF (Figure 2), are discussed in this section.

The livelihoods approach

Just as the ecosystem approach has developed from an understanding of the need to manage target fish stocks and fishing in the broader context of the ecosystem, similarly the livelihoods approach (Ellis, 2000; Allison and Ellis, 2001) grew from a recognition of the need to place fisheries in a larger context of households, communities and socio-economic environments.

Adopting a livelihoods thinking into EAF implies that fisheries management must look at fishers and fishing fleets in the context of where fishers live, in households, communities and fishery-based economies – just as it deals with the fish in the context of where the fish live, the ecosystem. Fisheries management thus deals with the fishery as one of a portfolio of livelihood sources (if such alternatives exist) and as potentially linked, through livelihoods, to other economic sectors.

A livelihoods approach can inform fisheries management in a number of ways, which may, if desired, be incorporated as well into EAF management:

- demographic: population and population trends, migration, age and gender structure;

- sociocultural: community objectives, gender roles, stratification, social cohesion;

- economic: income and its distribution, degree of fishery dependence, markets;

- institutional: community organization and infrastructure, involvement of women;

- marine Infrastructure: wharves, markets;

- community infrastructure: cultural facilities, schools, religious institutions;

- non-fishing activities: boatbuilding, agriculture, tourism, industry; and

- policy: linking fishery objectives to broader regional and national policy goals.

Integrated management

Integrated management (whether of oceans, coasts, watersheds, etc.) is an approach, or mechanism, to manage multiple (competing) uses of a certain designated area – uses such as fisheries, aquaculture, forestry, oil and gas, mining, agriculture, shipping and tourism. This involves managing multiple stakeholders (e.g. local communities, industries) as well as interactions among people and ecosystems, and among multiple levels of government. The integrated management approach is typically characterized by attention paid to a multiplicity of resources (e.g. soil, water, fish stocks, etc.) and of habitats (e.g. open ocean, estuaries, wetlands, beaches, lakes, rivers, etc.), as well as a range of environmental factors (e.g. changes in water temperature, turbidity and acidity, chemical pollutants and water flows).

Typically, integrated management – like the EAF and the sustainable livelihoods approach – involves processes for participatory decision making and conflict resolution, and requires a range of information on characteristics of the designated area, from the local climate and the state of the ecosystem, to the relevant natural resources, and the human community (cultural, economic, social).

A key aspect of integrated management is the implementation of an institutional framework in which to manage the mix of components and interactions within the relevant system, incorporating these aspects within a wider context of humanenvironment interactions, institutional linkages, multiuse conflict, multistakeholder governance systems and the like. This aspect of integrated management, involving institutional frameworks and managing multiple uses, is similar to that of EAF, but operating in a multisectoral context (i.e. fisheries together with other marine, coastal and/or watershed uses, such as shipping, mining, etc.), rather than solely within the fishery sector. Thus, EAF and integrated management are very much complementary, needing to operate in synchrony even while their scope differs with respect to what is being managed.

Conclusions

Adoption of EAF management will, on the one hand, ensure that we take into account impacts of the broader fishery system (the ecosystem and relevant human elements) on fishery management, and at the same time, ensure that the broader consequences of management actions are assessed. The boundaries, the scale of management, and the scope of that management are all crucial factors to consider in implementing EAF management in practice. The EAF deals with the “bigger picture” around fisheries, specifically to allow us to encompass relevant factors affecting and interacting with management from across the fishery system and beyond. EAF management: (1) looks at managing target fish species and fishing activity within the context of the ecosystem; (2) looks at the fishery within a larger context of households, communities and the socioeconomic environment (with support from the livelihoods approach); and (3) considers fishery management in a broader institutional context of managing multiple resource uses (feeding into and interacting with integrated management approaches).

Further Reading

| - | You can view the full report by clicking here. |

August 2008