Anthropogenic factors in Panama

Panama is the largest isthmus in the world and has 290 km2 of coral reefs, composed of 70 species in the Atlantic and 25 on the Pacific, with the majority found in the Caribbean Atlantic region. Panama has genetically distinct corals, which have been greatly affected by increasing ocean temperatures due to El Niño as well as a variety of other factors. Reported anthropogenic sources negatively affecting coral populations are ship grounding, herbicides, deforestation and overfishing. Overfishing has been cited as having the greatest impact likely in more distant locations and deforestation and soil erosion reported to be the main cause closer to the main land. Deforestation would be an infrequent and periodic yet overfishing more constant and continuous.

Although fishing in Panama provides 15,000 jobs with 131,000 tonnes of seafood taken annually (National Institute of Statistics and Census), a complete lack of management of marine protected areas and the absence of any fishing regulation has negatively impacted marine life, including corals reefs. Unregulated marine harvests contributes to in an imbalance of the ecology between fish and corals. Interactions between different trophic levels help to create stability between coral growth and predator/prey populations in the coral reef habitat. Of particular importance are the marine herbivores that graze on types of algae that grow on corals and compete with them for space and survival. Recent studies suggest that a greater diversity of species on coral reefs will provide protection against algal proliferation.

Artisanal and commercial fishing in the marine protected areas off the coast of Panama has resulted in severely diminished populations of lobsters, a collapsed scallop fishery, drastically reduced shark populations (shark fin soup) and more reduced catches of fish (Captain Dave Murphy, Boca Chica, Panama). In addition, it has been estimated an additional 40% of the total yearly catch goes unreported.

The Mighty El Niño - bleaching has the greatest impact

Corals have been reduced in abundance by 50-80% in the Caribbean near Panama over the past 30 years with coral mortality reported regularly in all other areas on both sides of the isthmus. The more recent major el Niño event, of 2015-2017 that has caused extensive coral bleaching and coral mortality due to increasing temperatures at the pristine Secas Islands, 27 km off the coast of Boca Chica, Panama, has been well documented (Reef Encounters, December, 2016, pg 45-48).

Bleaching due to increased temperatures from the warmer water currents of the eastern Pacific traveling westward has been studied by more than a few scientists in recent decades. The often shocking snow white color of the corals is due to the loss of the symbiotic algae that live within the coral tissue. The algae provide food in exchange for shelter, and access to waste from coral tissue which the algae use as a source of nutrition.

The exact temperature increase and duration that causes coral bleaching is well known. With temperature increases as little as 1 degree C for several months continuous, the corals expel the algae in order to survive. Reasons reported for this are so that the increased metabolism of the algae due to the increase in temperature and light would not damage the coral tissue. In other words, the coral needs to find a symbiotic partner that is better suited to the increased ocean temperature.

Corals can only survive brief periods without their algal symbionts, and many coral colonies die from the stress of a bleaching event. However, some corals adapt to the increasing temperatures by accepting and harboring new algal species that are better adapted to the increasing temperatures. As the color of the coral is provided by the algae, the new algae species results in new and often startling, beautiful colors of corals, some of which may have never been seen before (www.newaquatechpanama.com).

The long term study of the area of Secas Islands has provided valuable insight into the understanding of how pacific corals of Panama react, adapt and survive after bleaching. However, it is unknown if all coral reef sites in the Pacific Ocean of Panama are affected in a similar manner. Furthermore, Secas Islands is virtually unknown compared to the larger and more southern island of Coiba, which is touted to be one of the best diving sites in Central America.

Coiba Island corals

Coiba is composed of 38 islands covering 380,000 acres which was declared a national park in 1992 and world heritage site in 2005. Previous to this, Coiba island was been a penal colony established in 1919 and surprisingly, the prison was reported to have only shut down officially in 2004.

Coiba Island is the largest Island on the Pacific Coast of Latin America. It has been documented as having the largest coral reef in the Western Pacific, providing habitat for 760 species of fish, 33 species of sharks and 20 species of whales and dolphins. The big island has the reputation as being one of the best tourist destinations and surfing spots on the Pacific coast of the Americas. Regrettably, previous reports indicate that 75% of the corals of Coiba were killed due to the bleaching event of 1982, including extinction of some species.

Recent site visit and evaluation of Coiba Island corals

Two of the most popular sites for seeing corals at Coiba were visited on December 10 and 11, 2016. The condition of corals was well documented with 1000s of photos and narratives for three sites (www.newaquatechpanama.com). The results showed that the low lying branching coral known as Pocillopora, which makes up the majority of all corals in the Pacific ocean of Panama (personal observation), was experiencing stress only in the deeper (>3 m) open water displaying a dark brown color. For coral reef enthusiasts and saltwater aquarists, this "browning" condition is well known as an indicator of coral stress which leads to eventual death unless water quality conditions are quickly changed for the better.

However, like the Secas Islands that are 33 miles away, there were many Pocillopora colonies surviving the el Niño event, that were in excellent condition displaying unique colors due to different algal symbionts. These healthy low lying branching corals were found in rocky, more protected, shallow water sites at Coiba. It is likely that these shallow water corals are more adapted to changing temperatures giving them an advantage to survive higher temperatures from the intense recent el Niño. The same species and conditions at Secas Islands resulted in widespread mortality of deeper, open water Pocillopora colonies. Higher mortality of off shore, deeper water Pacific corals of Panama during previous el Niño periods has been well documented (Dr Peter Glynn, Miami University).

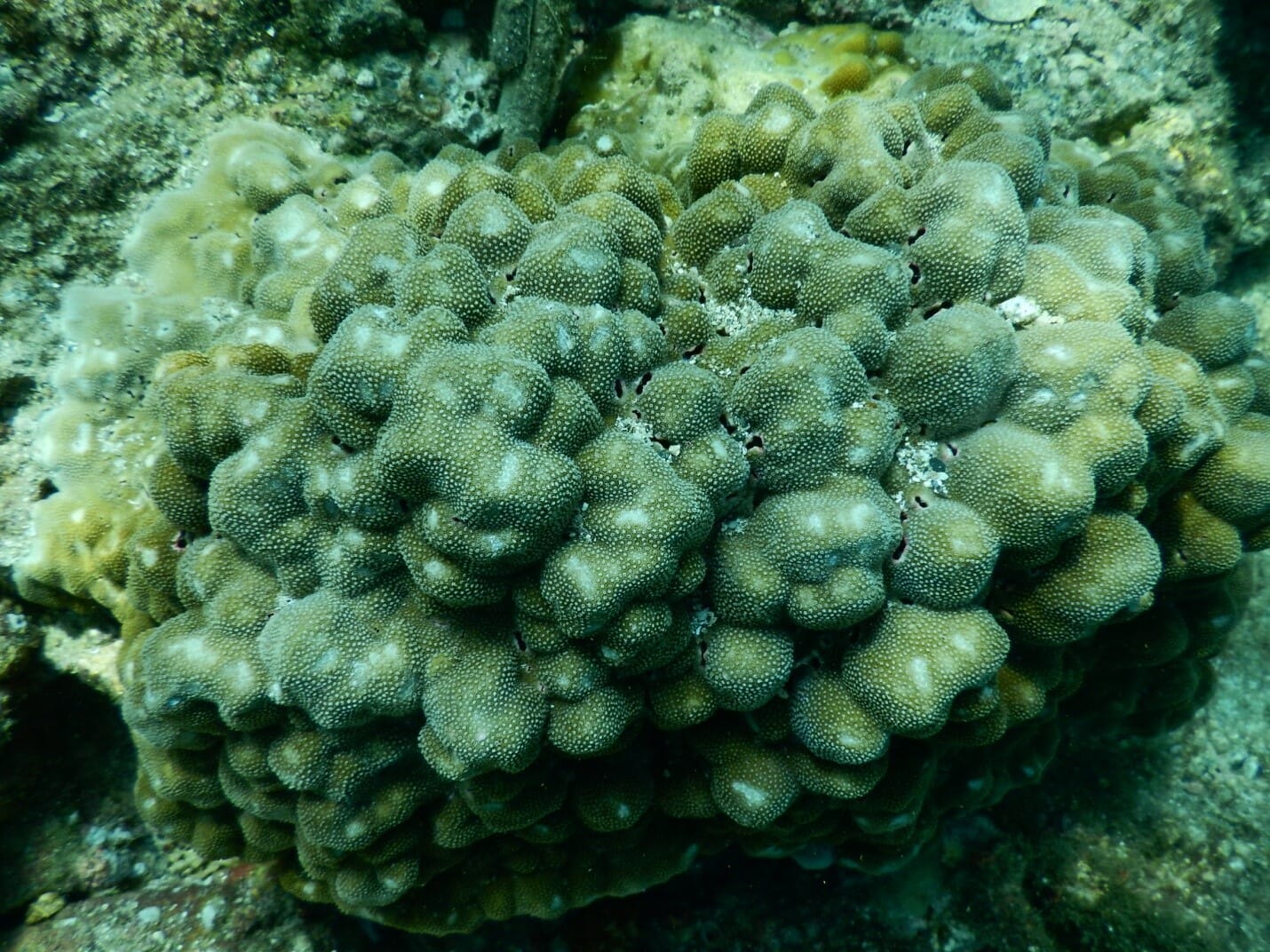

Larger mound corals at Coiba displayed an unusual, never seen before condition of multiple color algae symbionts in a single colony indicating stress, likely from increasing temperature as experienced by corals worldwide. Previous observations over 5 years at Secas Islands have shown that the El Niño event caused color changes in Porites corals for well over a year during the recent 2015-2016 El Niño event, but this did not result in mass mortality. Thus, this is the biggest difference in response of increased temperatures between these two major species of pacific corals of Panama at the sites visited.

Porites, for the most part, survived the increased temperature by exchanging algal symbionts (colors) while the 3x faster growing Pocillopora succumbed to a greater degree from bleaching due to the increased temperatures which has been documented in great detail at Secas Islands (www.newaquatechpanama.com).

Healthy coral colonies could be found in numerous locations around the small islands of Coiba indicating that very likely these corals will survive the El Niño by exchanging algal symbionts, and re-establishing colonies from more adapted ones in shallow waters at these sites visited.

More information and pictures can be found at www.newaquatechpanama.com