Click on the figure to enlarge. © MacLeod et al, 2020

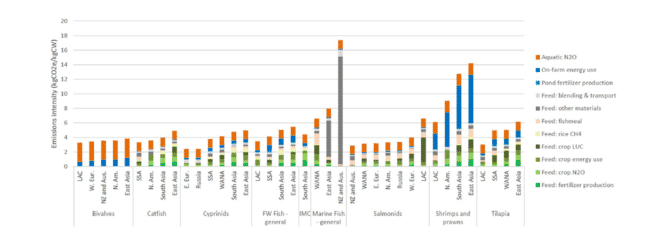

So reveals a new study, which looks into the emissions produced by nine of the main groups of cultured aquatic species. They quantified GHG emissions from various stages of the aquaculture cycle including the production of the raw materials used in making fish feeds, the processing and transport of these materials; the production of the feed and its transport to the fish farm; and the rearing of the aquatic animals themselves.

Significantly, the analyses do not calculate the processing or transport of finished aquatic product and – given the hugely international nature of seafood supply this is a major shortcoming.

The nine major aquaculture culture groups assessed – bivalves, shrimps/prawns and finfish (catfish, cyprinids, Indian major carps, salmonids and tilapias – accounted for 93 percent of global aquaculture production.

GHG emissions from this group totalled 245 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e). By extrapolating this figure for the remaining 7 percent of production they estimated that emissions for all shellfish and finfish aquaculture during 2017 would have been 263 MtCO2e.

Relative intensity

The researchers note that GHG emissions tend to correlate closely with production for most species-groups, for example cyprinids account for 31 percent of emissions and 31 percent of production. However, they note exceptions – at one end of the scale shrimp production accounts for 21 percent of emissions but only 10 percent of production, while bivalves produce 7 percent of emissions but represent 21 percent of production.

Key areas of GHG emissions

They calculate that production of crops for aquaculture feeds accounted for 39 percent of the industry’s emissions. When the emissions arising from fishmeal production, feed blending and transport are added, feed production accounts for 57 percent of emissions.

“The bulk of the non-feed emissions arise from the nitrification and denitrification of nitrogenous compounds in the aquatic system (‘aquatic N2O’) and energy use on the fish farm (primarily for pumping water, lighting and powering vehicles),” they explain.

Click on the figure to enlarge. © MacLeod, et al, 2020

Emissions intensity

According to the study the species with the highest emissions intensity (EI) are marine fish “due to the assumption that the ration in East Asia (and New Zealand and Australia) is 100 percent low value fish/trash fish (which has a higher EI than most crop feed materials) and the higher feed conversion ratio".

Shrimps and prawns have high EI, due to the greater amounts of energy used for water aeration and pumping. By contrast, bivalves have the lowest EI as they have no feed emissions, relying on natural food from their environment.

Aquaculture vs terrestrial livestock

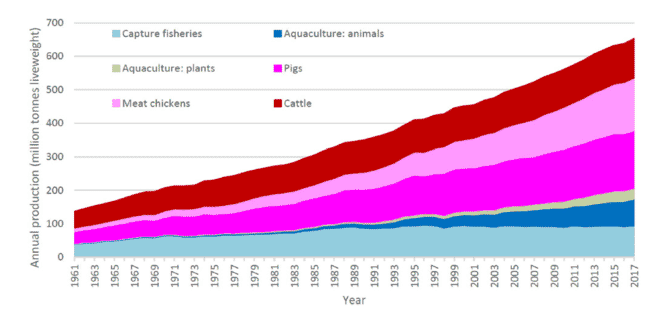

The researchers then compared aquaculture emissions with the FAO figures relating to emissions generated by livestock production, concluding they are lower than livestock because livestock production accounts for three times as much protein production and because livestock – in particular ruminant species – have a higher emissions intensity than aquaculture, due largely to the high fertility and low feed conversion ratios of fish.

Room for improvement

However, the researchers conclude that “moderate GHG emissions from aquaculture should not be grounds for complacency. Aquaculture production is increasing rapidly, and emissions arising post-farm, which are not included in this study, could increase the emissions intensity of some supply chains significantly. Furthermore, aquaculture can have important non-GHG impacts on, for example, water quality and marine biodiversity. It is therefore important to continue to improve the efficiency of global aquaculture to offset increases in production so that it can continue to make an important contribution to food security.”

Further information

The full study is published is accessible in Nature Research, under the title "Quantifying greenhouse gas emissions from global aquaculture".