Although primarily regarded as a condition affecting first season rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), all salmonids can become infected during freshwater stages with varying severity. Although the name PKD was first coined by Roberts & Shepherd in 1974, reports of a similar syndrome affecting trout date to at least 50 years previously. The disease is endemic in large areas of Western Europe and North America, but has not been recognised in the Southern hemisphere to date.

Aetiology

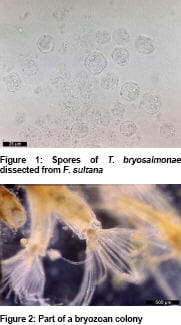

The identity of the enigmatic causative agent of PKD – originally denoted as PKX - remained elusive until the late 1990s when it was established to be a myxozoan whose spores possessed four distinctive polar capsules (Figure 1) and which also parasitized freshwater Bryozoa, invertebrates colloquially known as ‘moss animals’ (Figure 2). The parasite was consequently named Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae in reference to its two known hosts.

Various freshwater phylactolaemate bryozoans including Fredericella sultana have since been found to become infected with T. bryosalmonae resulting in the development of spherical sacs (Figure 3) which release spores. These are released into the surrounding water where they can infect salmonid fish. Massive numbers of spores can be produced from relatively small volumes of bryozoans, with recent research suggesting that very low numbers are capable of infecting fish to result in disease.

Epidemiology

PKD has traditionally been perceived as a seasonal disease, outbreaks being largely limited to the warmer months of the year when the water temperature exceeds 12 ºC. As spores of T. bryosalmonae have been detected in infected waterways all year round, the temporal limits of disease manifestation have been attributed to temperature effects on parasite development in fish tissue. Although affected by water temperatures, the incubation period in the fish is approximately 7 weeks, with a self-limiting clinical course of usually 2-3 months.  On infected farms, morbidity levels can approach 100% while mortality levels varying widely depending on the impact of secondary factors such as concurrent diseases, environmental conditions and management practices. In addition to affecting first season rainbow trout, older year classes which are naïve to T. bryosalmonae exposure can also become infected. Those fish which survive clinical disease prove resistant to subsequent challenge, signifying the development of protective acquired immunity.

On infected farms, morbidity levels can approach 100% while mortality levels varying widely depending on the impact of secondary factors such as concurrent diseases, environmental conditions and management practices. In addition to affecting first season rainbow trout, older year classes which are naïve to T. bryosalmonae exposure can also become infected. Those fish which survive clinical disease prove resistant to subsequent challenge, signifying the development of protective acquired immunity.

Clinical Signs of PKD

External signs are non-specific and may include:

- Body darkening

- Gross abdominal swelling

- Exophthalmos

- Gill pallor

- Loss of equilibrium and respiratory distress

Internal signs:

Internal signs:

- Granulomatous renal swelling, particularly of the posterior (up to ×10 of the normal size)

- Spenomegaly

- Generalised pallor

- Renal haematopoietic hyperplasia followed by granulomatous interstitial nephritis

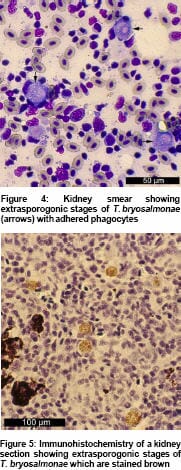

- Presence in kidney of extrasporogonic and sporogonic parasite stages

Diagnosis

Although not pathognomonic, characteristic clinical and gross pathological signs could support a putative diagnosis of PKD in conjunction with clinical history – especially the season of the year and records of previous farm outbreaks. However, definitive diagnosis relies upon the detection of T. bryosalmonae in samples of fish tissue.

Extrasporogonic stages – often encircled by phagocytes - can be readily identified by methylene blue, May-Grünwald-Giemsa or Leishman-Giemsa staining of kidney smears (Figure 4), or in fixed paraffin-embedded sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin or by immunohistochemistry (Figure 5) using T. bryosalmonae specific monoclonal antibodies such as P01 (Aquatic Diagnostics Ltd., Stirling, UK). Molecular techniques such as in situ hybridisation and polymerase chain reaction assays have also facilitated reliable diagnosis.

Prevention and Control

Currently, there are no licensed vaccines or treatments for PKD. In the past, malachite green, the antibiotic fumagillin DCH and its synthetic analogue TNP-470 have been used therapeutically with some efficacy, but concerns over toxicity to fish, residue levels and environmental issues have prevented wide adoption of these treatments.

Husbandry measures including lowering summer water temperature (using bore-hole water), delaying transfer of naïve stocks to endemic waters until later in the year (to allow acquired immunity but not clinical disease to develop), eliminating secondary pathogens and reducing feeding rates have been implemented in attempting to limit economic losses.

Much interest has focused on controlling bryozoan proliferation of inlet waters to farms, but the high level of infectivity of the innumerable spores released from relatively small colonies of bryozoans would mean that such control measures would have to be meticulously successful to confer protection to stock. Further research continues into vaccine and chemotherapeutant development with several possible candidates envisaged.

November 2006