With just over half of all the world’s seafood now coming from aquaculture, the industry is increasingly relying on science for sustainable growth and innovations. While more science is becoming freely available to aquaculturalists, policy makers, managers and other stakeholders, new research led by Dr Jeff Clements (DFO Gulf Fisheries Centre, Canada) suggests that some of this “open-access” aquaculture science is not quite what it seems.

Traditionally, science articles have been kept behind paywalls by publishers, only available to those who subscribe to the journal or pay for access to an individual article. But in the case of open-access research, authors are charged a fee to publish instead.

“Accessing science is expensive,” Clements explains. “Open-access scientific publishing is a recent adoption by the scientific community to make peer-reviewed content freely available to anyone on the internet.”

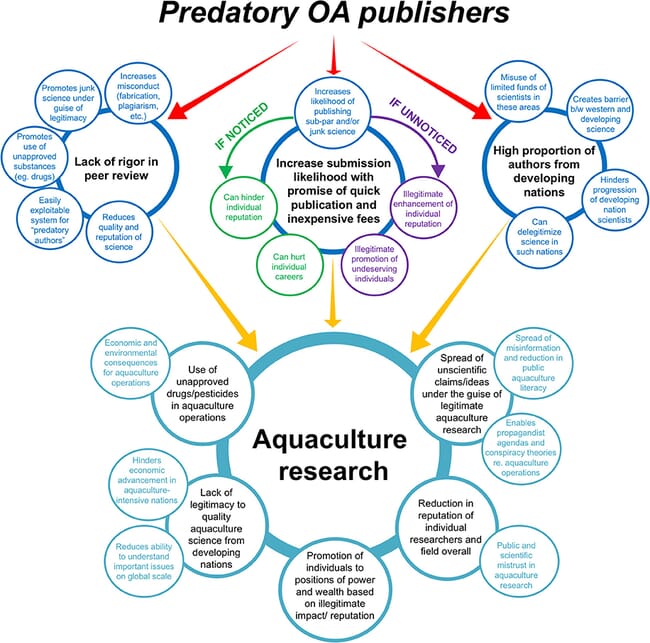

Sadly, some seek to exploit the open-access model to make easy money. Popularly known as “predatory journals”, these journals are less rigorous about what they do and do not publish.

The primary problem with predatory journals is that the articles published on their platforms do not undergo rigorous peer review. Under the conventional peer-review process, once an author submits a paper to a journal for consideration, the journal will then send it out to other scientists for their review. The reviewers normally ask for revisions. Only when the reviewers agree that the work is of a sufficiently high quality does the science gets published. If the work is insufficient, the paper is rejected.

“Peer review is important because we need to make sure that science is as rigorous and as accurate as it can be,” Clements explains. “If I write a paper and publish it without anyone else reading it, it’s not going to be the best it can be, and there could be major flaws.” While this process normally takes a long time, “some of these [predatory] publications are publishing a day or two after submission,” Clements notes.

To see how prevalent predatory open-access journals are in aquaculture, Clements and fellow scientists decided to put themselves into the shoes of aquaculturalists and other stakeholders.

“We used a Google search to identify these journals. We wanted to mimic what a non-scientist would do to find scientific information on aquaculture,” Clements says. Their search involved simple keyword strings such as “journal of aquaculture”, “journal aquaculture” and “aquaculture journal”. Then, to see how many of the open-access journals that were returned in the first 10 pages were potentially predatory, the team split the journals up into those that were indexed in dedicated and reputable databases used by scientists, and those that weren’t.

For the team, the results were disheartening. Non-indexed journals were three times more abundant in their searches than indexed journals. And although not all non-indexed journals are predatory, a sizeable proportion of the journals the scientists found set off alarm bells.

For aquaculturalists, the repercussions of following poor-quality science might be serious. Ineffective or harmful pharmaceuticals and other treatments may be promoted as good treatments, for example. Or aquaculturalists may spend money and time altering working processes with the false promise of enhancing their efficacy or environmental sustainability.

“Policymakers, managers, fish farmers and the general public rely on sound, reliable science for a successful and sustainable aquaculture industry,” says Clements. “If they aren’t trained to properly recognise good science from bad science, they run the risk of interpreting predatory open-access journals as high-quality scientific journals.”

Evading the predators

Spotting an open-access predatory journal is no easy task, and there is no foolproof way to guarantee you won’t be reading substandard science. But there are a few things you can do to help make sure that the science you are reading has been published by a reputable journal.

The simplest (and probably the most reliable) step is to use the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), rather than your favourite search engine, to find journals or articles. This “whitelist” database only lists reputable open-access journals. Although not all reputable journals are included on the DOAJ, disreputable journals are not.

If you prefer to use a search engine, then you may need to do a little detective work. Here are six things to look for on a journal’s website (normally in an author guidelines section) that, in combination, suggest that it might have a predatory business model – and that the science within is therefore worth viewing with a sceptical eye:

- Predatory journals typically started publishing from 2010 onwards.

- Predatory journals usually publish fewer than 20 articles a year.

- Predatory journals typically charge less than US$1,000 to have work published, and often charge around $300-400.

- Predatory journals tend to publish articles in less than 80 days following initial submission by author.

- Beware if the article is a piece of original research but contains very poor or no statistical analysis.

Finally, for ultimate reassurance that the paper you’re reading has been published by a reputable journal, do an online search for members of the title’s editorial board. You should be able to find the board members easily and they should have an affiliation with a research institution such as a university or government agency.