White spot syndrome virus (WSSV), is one of the most virulent diseases to impact the shrimp aquaculture sector, and is estimated to cause 10 percent of the sector’s losses – equating to hundreds of millions of dollars a year. But the portal of entry into individual shrimp has kept researchers guessing – until now. It’s a mystery that Hans Nauwynck, a professor at Ghent University, has been puzzling over for over a decade.

“White spot is known as ‘the killer’ – it kills infected shrimp within 72 hours and was one of the major issues in the shrimp sector, which is why we decided to direct our research there,” he explains.

Previous research by Nauwynck’s group demonstrated that shrimp can neither be infected by immersion in water containing WSSV, nor by peroral inoculation – there was no obvious way for it to gain entry, either via the digestive tract or the cuticulum.

“For me as a virologist this was the biggest question of my life – how do shrimp become infected?” he reflects.

Nauwynck discussed this with one of his research group, Thuong Van Khuong, and it was Van Kuong’s insights that were to lead to the discovery.

“I said to Thuong, there should be a place in the animal that has no cuticulum and he said, ‘yes professor, there’s a place, the antennal gland’,” Nauwynck explains.

Members of the group, including Van Kuong and Gaëtan De Gryse, then began to focus on the morphology of the antennal gland.

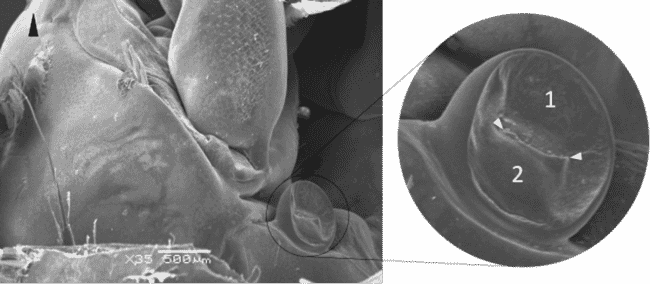

The black arrowhead point to the two valves of the nephropore. The two white arrowheads point to the slit-shaped opening. © Hans Nauwynck

Portal for pathogens

The group’s work showed that the “gland” is a key portal for pathogens – a means of entry that is not protected by an impermeable cuticula. This was supported by attempts to infect shrimp with WSSV using an extremely thin catheter to bring the virus directly into the “gland” via the nephrophore.

“By doing that we could clearly see that we could cause an infection and that this is the target organ. Because it’s the target organ, we then wanted to know what it looked like, in more detail,” Nauwynck recalls.

And their research revealed that this so-called gland was considerably more complex than previously thought. Having discovered that it contains a kidney, a bladder and a large network of bags – and demonstrated that it plays an important role during moulting and growth – they suggested a new name for it: the nephrocomplex.

How the nephrocomplex allows shrimp to grow

As well as these insights into the morphology of this region of the shrimp’s head, they also – inadvertently – solved another enigma: revealing the mechanism of how shrimp moult and therefore how they grow.

They discovered that, by filling the bags within the nephrocomplex with water, pressure rises inside the shrimp till the old cuticula (shell) shears, which allows the animal to shed its cuticula. By further filling the bags, the volume of the shrimp increases before the soft new cuticula, which was already present underneath the old cuticula, hardens again. It’s a process that occurs every nine to 13 days.

“It’s a side-effect of our virological study. I was very happy to find this, because knowing how shrimp grows can have a huge impact,” says Nauwynck.

After emptying the bladder during urination, a slight vacuum is present, causing the influx of a small volume of water. If this water is contaminated by pathogens the nephrocomplex acts as the point of access. As well as WSSV, other key pathogens afflicting the shrimp sector include bacteria such as Vibrios, which are responsible for conditions such as early mortality syndrome (EMS).

They also noted that a decline in the salinity of the water makes the shrimp particularly vulnerable to pathogens.

“It’s very interesting to correlate this new finding with what the farmers have seen in nature, for example the well-known fact that white spot outbreaks tend to occur after rainfall. It also means that farmers, knowing about the effect of osmotic stress – for example when they are changing the water, these are all aspects of how new techniques might be taken into consideration,” notes Prof Patrick Sorgeloos, also of Ghent University, who is a champion of Nauwynck’s research.

“With all these findings, it will be possible to accelerate the growth of shrimp and to protect shrimp against pathogens,” the paper, in which the findings are published, concludes.

Looking ahead

Despite Nauwynck’s breakthroughs in shrimp morphology, he notes that attracting funding for fundamental research is still not easy.

“It takes me sometimes five years to get funding for simple research – this is a major issue and a major problem. You can have arty-farty transcriptomics, but if you don’t have the basics, you don’t have fundamentals, you cannot do it,” he reflects.

Nevertheless, he now aims to investigate the lymphoid organ.

“I’m convinced there’s full control of the portal of entry for pathogens – similar the harderian glands in the eyes of chickens. But you might need 10 PhDs to answer that question, so it might not happen before I retire. But finding the portal of entry is opening new doors for new fundamental research, the only question I have is who will sponsor that – it’s a big fight, but a challenging one, so I’ll keep on going,” Nauwynck concludes.

Further information

The full study, published under the title “The shrimp nephrocomplex serves as a major portal of pathogen entry and is involved in the molting process”, is now accessible via the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.